As Chris Salewicz's "Bob Marley: The Untold Story" isn't the first to report, many human beings worldwide -- he cites Hopis, Maoris, Indonesians and, of course, Africans -- regard Bob Marley as a "Redeemer figure coming to lead this planet out of confusion," and some consider him nothing less than the literal second coming of Jesus Christ. Say what you will about the adoration accorded John Coltrane, John Lennon, Elvis Presley, Michael Jackson, Um Kulthum, this is another order of iconicity. Say what you will about the religious dimensions of pop fandom, Marley's Rastafarianism renders the metaphor literal. These mystifications bode ill for Marley's biographers, who number at least 15 or 20 by now. Take, for instance, Stephen Davis, who closes with two triple-indented lines: "Bob Marley lives. He's a god./'History proves.'" And Davis' bio is one of the good ones.

Maybe it's the ganja -- well, definitely it's the ganja, with its built-in third eye, its aura of secret significance. More fundamentally, though, it's the transport, the release -- the suprarational rewards music lovers love music for, which Marley claims are owed solely to the divinity of the Ethiopian autocrat Haile Selassie. Who are we to gainsay him, especially we white Babylonians? He has bestowed upon us this feeling of transcendence, and not only that, articulated a political consciousness that needs articulating. "I remember on the slave ship/How they brutalized our very souls/Today they say that we are free/Only to be chained in poverty" might not turn many heads at a socialist scholars conference, but by pop standards it's a smart, blunt, hard-headed augury of militance. As a result, many all too readily suspend their disbelief when the politics turn out to herald twistier "reasonings," as Rastas call their stoned biblical bull sessions.

Maybe it's the ganja -- well, definitely it's the ganja, with its built-in third eye, its aura of secret significance. More fundamentally, though, it's the transport, the release -- the suprarational rewards music lovers love music for, which Marley claims are owed solely to the divinity of the Ethiopian autocrat Haile Selassie. Who are we to gainsay him, especially we white Babylonians? He has bestowed upon us this feeling of transcendence, and not only that, articulated a political consciousness that needs articulating. "I remember on the slave ship/How they brutalized our very souls/Today they say that we are free/Only to be chained in poverty" might not turn many heads at a socialist scholars conference, but by pop standards it's a smart, blunt, hard-headed augury of militance. As a result, many all too readily suspend their disbelief when the politics turn out to herald twistier "reasonings," as Rastas call their stoned biblical bull sessions.

So when I noticed Salewicz embellishing his first-chapter account of Marley's fatal cancer with matriarch Cedella Booker's conspiracy theories and backup singer Judy Mowatt's lightning-bolt premonition, I said uh-oh. But these were feints. Davis' "Bob Marley" is wrenching on Marley's final months, Timothy White's "Catch a Fire" provides unmatched blow-by-blow on the Marley estate, and both bring their own details to the life story proper. But Salewicz's book is faster, fuller and fairer than either. It's faster because through plenty of incident it sticks to the story, a welcome improvement on Salewicz's bloated 2007 Joe Strummer bio. It's fuller due not to Salewicz's relatively late and limited personal contact with his subject, but to the spadework of the 11 other biographers he cites, the low-lying fruit he picked up during two years of living in Jamaica, and what looks from here like some plain old digging. As for fairer, well, Salewicz admires Bob Marley deeply without deifying him. That's what I call reasoning.

Marley was born in 1945 to the 18-year-old daughter of a locally prominent black family in the Jamaican high country and a much older white bureaucrat who married the mother but barely knew the son. He moved to Kingston's Trench Town ghetto at 12 and cut his first record at 17. For the next decade, he and fellow Wailers Peter Tosh and Bunny Livingston grew in skill and Jah love as they negotiated the rough and tough Jamaican music business. Advised by a motley crew of thuggish Kingston minimoguls, devious Rastafarian elders, and small-time American bizzers, twice joining his mother in Delaware to replenish his capital in working-class jobs, he and the Wailers were the biggest thing in Jamaica by 1970. They performed in the States, undertook an abortive Swedish film project, and ended up in London. And in early 1972 they connected with Island Records' Chris Blackwell, the great white record man who staked them to the breakthrough album "Catch a Fire."

For most of his fans, Marley equals his Island output, and understandably so. Not only does it remain music of the highest quality, it was the engine of the cultural, spiritual and political quest that led to his deification -- his "legend," to cite the title of the Island compilation that has poured from the dorm rooms of millions of stoners since 1984. Nevertheless, this output reflects only a quarter of his tragically foreshortened 36-year life, for the previous quarter of which Marley was just as prolific. More than White and much more than Davis, though in less musical detail than the scrupulous academic Jason Toynbee (whose study is titled, what else, "Bob Marley"), Salewicz respects this truth without tackling the monumental job of codifying it. Near as I can count, the 1970 Jamaican hit "Duppy Conqueror," later rerecorded for "Catch a Fire's" ruder, stronger follow-up "Burnin'," has appeared on some 300 Marley and reggae comps.

The first disc-plus of Tuff Gong's "Songs of Freedom" box is a good introduction to Marley's strictly Jamaican period, overlapping only slightly with Sanctuary's highly recommended "The Essential Bob Marley & the Wailers" and barely at all with Heartbeat's earlier, weaker "One Love at Studio One 1964-66." But none of these include "Nice Time," "Treat Her Right," "The World Is Changing," or "Black Progress," all of which Salewicz tipped me to, or the Toynbee faves "I'm Still Waiting" and "Jailhouse," not to mention "Milk Shake and Potato Chips," a touching trifle I streamed because I liked the title. There's not all that much sense to be made of a discography that embraces half a dozen producers, a hazily documented myriad of backup musicians, and material ranging from "Black Progress" to "Milk Shake and Potato Chips." But dip in and many things become clear.

As a teen, Bob would do anything for a hit, including covers of "And I Love Her" and "What's New Pussycat." He loved American soul music but wasn't always so great at it. He was militant early, as on 1968's "Bus Dem Shut (Pyaka)," "bus" meaning "bust" and "pyaka" meaning "liar." He was on top or ahead of every rhythmic shift in Jamaican pop and several elsewhere. He shared with certain country songwriters the ability to express deep content in simple language, both personal (think Hank Williams) and social (Merle Haggard). And most important in the long run, he had the gift of tune, devising songs so compelling that many from his 1969-71 flowering were inevitably reprised on Island: "Concrete Jungle," "Slave Driver," "Small Axe," "Trench Town Rock," "Lively Up Yourself," "Kaya."

There are purists who claim Marley's music went north once he signed with Island, or broke with Tosh and Livingston, or enlisted American guitarist Al Anderson. But Salewicz isn't among them. Like most observers, he sees Blackwell as an essentially benign force who helped Marley achieve "the international sound we were expecting to have" -- a quote not from Marley but from Livingston, who felt so ill at ease in Babylon that he rejected the touring life for a sporadically inspired solo career as Bunny Wailer. Marley's internationalism was better assimilated in Britain, where Jamaicans dominated the small black population, than in the U.S., where, as Marley knew all too well, a much larger black population preferred competing musics of its own. A cordial but ultimately rather private man, Marley drove himself hard, perfecting his stagecraft and writing a song a day as he studied scripture, pondered politricks, acted the don, played soccer barefoot, bedded innumerable women, and fathered what Salewicz reckons as 13 children by eight of them including his wife Rita, though estimates do vary.

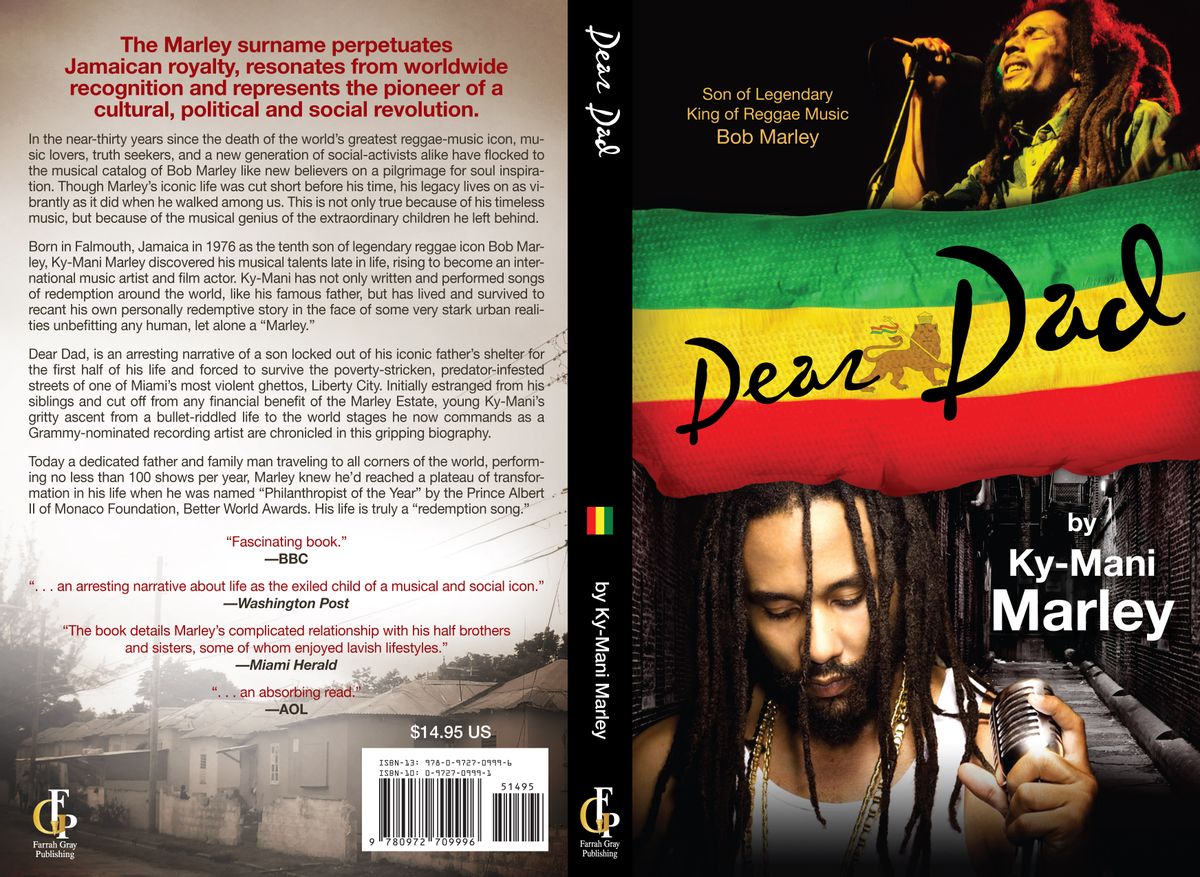

Unsurprisingly, Marley's choices and circumstances embroiled him in contradictions. I hesitate to say his insatiable womanizing is the least of them, especially since some of his kids had it so much better than others -- his son Ky-Mani's "Dear Dad" is a much better book about growing up in a drug-dealing culture than about music or his dear dad. But at least it's a familiar pattern. Less so the man of peace who delivered the occasional beatdown and hired ropey-haired toughs who promoted his records by delivering many more. And what are we to make of the Marley who Salewicz reports watched the private executions of three men who'd tried to assassinate him shortly before his 1976 Smile Jamaica concert -- a comeuppance that came down a week or so after his 1978 One Love Peace Concert, which Salewicz unconvincingly judges "one of the key civilizing moments of the twentieth century" because Marley got two warring politicians to grasp hands onstage for an awkward spell? But I was in fact more shocked by the famously generous philanthropist dropping 35 grand on a Miami dinner with a daughter of the Libyan oil minister, 1953 Chateau Lafite Rothschild included -- and more saddened by Salewicz's account of Marley's embattled 1980 visit to a newly independent Zimbabwe, where Robert Mugabe's cohort was already proving more autocratic than Ras Tafari's.

To repeat, it was righteous of Salewicz to tell these tales. But that's only because they don't turn his book into a debunk. If it's foolish to deify Bob Marley, it's far more foolish to dismiss him, in effect blaming him for not living up to the magnitude of his achievement. Praise Peter and Bunny all you want -- they deserve it. But credit Marley's reservations: "Is like them don't want understand mi can't just play music fe Jamaica alone. Can't learn that way. Mi get the most of mi learning when mi travel and talk to other people." And recognize in that one-world bromide the seriousness of his cultural-spiritual-political ambitions. Salewicz reports that the assassins just mentioned were armed by the CIA, while others blame the right-wing Jamaican Labour Party. Probably not much difference, and either way you can trust his enemies to know his power. Most of the 14 million Americans who've bought the calculatedly anodyne "Legend" are in it for the herb. But Marley is very different for people of color such as the Tanzanian street vendors of Dar es Salaam's Maskani district, one of many third-world subcultures to integrate his songs and image into a counterculture of resistance.

Peter and Bunny wouldn't have brought Marley near such a consummation. Nor would the rhythmic muscle and dubwise byways of Lee "Scratch" Perry, whom the purists reasonably account Marley's best and toughest producer. In fact, it worked pretty much the opposite. The gunmen who invaded Marley's Kingston compound in 1976 managed to crease Bob's arm and Rita's skull. After playing the concert in bandages two days later, the two fled to England, where Marley took musical vengeance not by screaming bloody murder but by fulfilling his crossover dreams with heightened understanding, focus and subtlety. In six months he recorded all of "Exodus," which Time magazine hyperbolically declared the greatest album of the century in 1999, and the equally blessed "Kaya," which leads with the languorous "Easy Skanking" and climaxes with "Runnin' Away" and "Time Will Tell" -- this normally unalienated visionary's haunted meditation on the confusions of fame followed by a promise of justice no tougher than anything else on his gentlest albums sonically and his most acute aesthetically. "Exodus" and "Kaya" opened the door on a three-year period in which he cemented his international fame while fighting the cancer he might have beaten if Rastafarianism looked more kindly on Babylonian medicine, amputation in particular -- the disease began in a long-troublesome big toe he reinjured playing soccer barefoot.

Marley's big Kingston concerts didn't prevent Jamaica from turning into the most gun-ridden state in the western hemisphere. Lee "Scratch" Perry relocated to Switzerland. The Maskani district has been plowed under to make room for a bank. And reggae has evolved into a beat-dominated music of crotch-first sexism and toxic homophobia that's far livelier than the Bob-worshipping hippie and Afrocentric crap that surfaces wherever spliffs are smoked or tourists go dancing. In short, Bob Marley has yet to remake the world -- a failing he shares with just about everyone else who's tried. But that doesn't mean he hasn't changed it. Gandhi and King and Mandela didn't leave utopias behind either, and unlike them, Marley was merely a musician no matter how much praise he proffered Jah. His music is as firmly ensconced in the pop pantheon as the Beatles' or James Brown's, and it signifies a remade world even if that doesn't make it so.

A Redeemer? We don't play that. "Redemption Song"? That we play. "Won't you help to sing, these songs of freedom/Cause all I ever had/Redemption songs, redemption songs/Redemption songs."

Shares