Ennui is a difficult state to describe. It's a depthless feeling -- part boredom, part discontent, part torpor. It is a look especially suited to the French, since we Americans often lack the gravity to make flatness meaningful. But Bret Easton Ellis is a skilled and subtle writer of ennui; he writes with sensitivity about characters whom we wouldn't mind sucker-punching. Ennui is a narrow feeling, and his new novel "Imperial Bedrooms" is, correspondingly, a book with a tiny but complex purview. This isn't at all a bad thing.

The key to Bret Easton Ellis might lie in the epigraphs. "Imperial Bedrooms," the sequel to that author's first novel "Less Than Zero," opens with words from Elvis Costello and Raymond Chandler. "Less Than Zero" quotes Led Zeppelin and X on its prefatory pages. If the four sources have anything in common, it's a distinct genius at posturing -- at generating an artful, meaningful fakery. Ellis' characters are actors by instinct, some by profession. They're not about to show their hand. Party conversation, cars and clothes are the signifiers through which we are to understand them. These things may look superficial, but remember, they constitute the surfaces of people who pay a lot of attention to surfaces. Ellis doesn't go for expository internal monologues. He tells us who fake-hugs whom and lets us extract from that what we can. A reader would not be amiss in noting similarities between the author and his epigraph sources. Artful fakery is tricky, interesting stuff. When it fails -- as it does for the main character of "Imperial Bedrooms" -- it fails big.

The key to Bret Easton Ellis might lie in the epigraphs. "Imperial Bedrooms," the sequel to that author's first novel "Less Than Zero," opens with words from Elvis Costello and Raymond Chandler. "Less Than Zero" quotes Led Zeppelin and X on its prefatory pages. If the four sources have anything in common, it's a distinct genius at posturing -- at generating an artful, meaningful fakery. Ellis' characters are actors by instinct, some by profession. They're not about to show their hand. Party conversation, cars and clothes are the signifiers through which we are to understand them. These things may look superficial, but remember, they constitute the surfaces of people who pay a lot of attention to surfaces. Ellis doesn't go for expository internal monologues. He tells us who fake-hugs whom and lets us extract from that what we can. A reader would not be amiss in noting similarities between the author and his epigraph sources. Artful fakery is tricky, interesting stuff. When it fails -- as it does for the main character of "Imperial Bedrooms" -- it fails big.

In the case of "Less Than Zero," the failed posture was that of the book itself. That novel replicated the feeling of riding as a passenger on a long highway drive: it was hypnotic, boring, and required little of a reader. Ellis is a good writer, but he was not then good enough to excuse breathtaking successions of words like "Ferrari," "cowboy hat" and "astrologer" packed within the space of one inch. His adolescents offered fewer interpretive possibilities than the adults of "Imperial Bedrooms." They were bad actors. When I originally checked "Less Than Zero" out of the library, years ago, I found a pubic hair lodged between two pages, and this seemed significant.

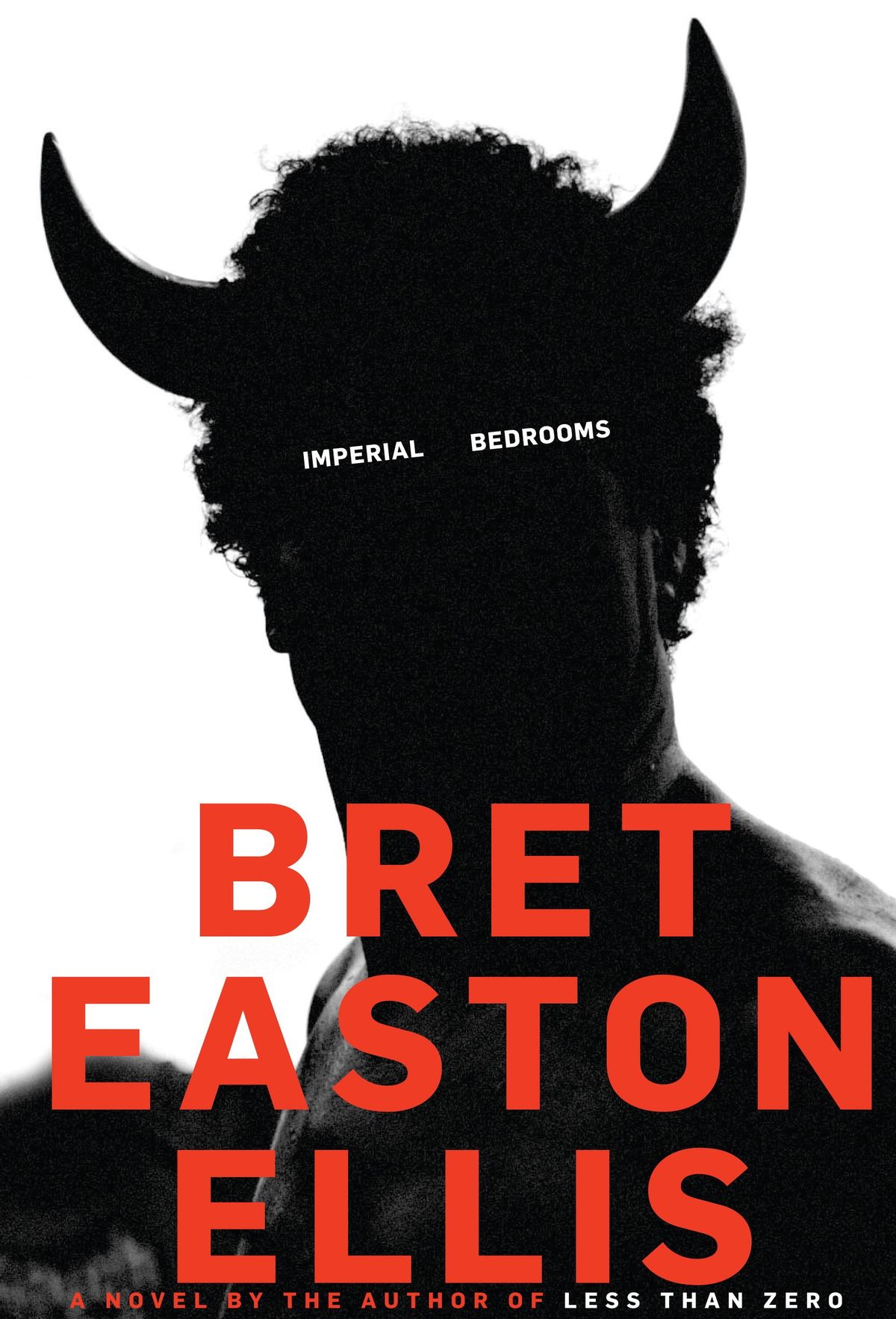

"Imperial Bedrooms" resembles its predecessor. It is a thin novel, with Lego blocks of text stacked in short chapters. The narrator is named Clay, but he is a different Clay than the narrator of "Less Than Zero." "They had made a movie about us," "Imperial Bedrooms" begins. "The movie was based on a book written by someone we knew. The book was a simple thing about four weeks in the city we grew up in and for the most part was an accurate portrayal." The Clay of "Imperial Bedrooms" is the Clay upon whom "Less Than Zero" was ostensibly based.

We find our man, a screenwriter, back home in Los Angeles after four months of sojourn in New York. He chews Altoids, drinks a lot and owns an Art Deco condominium "minimally decorated in soft beiges and grays" that is broken into shortly after his arrival. Nothing is stolen, but there has been tampering in Clay's absence: a computer turned on, a letter opener moved, a Diet Coke missing from the refrigerator. Around the same time, a blue jeep begins to tail Clay around the city, and he receives a text message that says, I'm watching you. A mystery is afoot.

A young blond actress named Rain is also afoot. Rain is an ingénue auditioning for a role in Clay's new movie; she is possessed of eyes "drained of intent, programmed not to be challenging or negative." Rain is unsuccessful but young, and she has transformed the taint of failure into a provocative neediness. Clay promises to get Rain cast in exchange for nude photos and sex, a contract common in his circles. Sex for the men and women of "Imperial Bedrooms" is a transactional matter of various holes being penetrated with various objects. The holes and objects are interchangeable, though generally the holes are attached to attractive people and the objects to powerful ones.

Readers will recognize the mood of the book as one of atmospheric doom. Southern California has this effect on a certain kind of writer, and, despite his callous characters, Ellis is as much a neurasthenic as Joan Didion in his perceptions of the place. Both writers are seismometers tuned to dread instead of ground motion, and everyday things might appear to them as sinister and significant as the glass of milk in "Suspicion." Clay locates shades of doom in spray-on tans and bleached teeth; he hears old Duran Duran songs and thinks, "Sadness: it's everywhere."

And it is. Clay falls in love with Rain only to find that she's a highly paid prostitute with unseemly connections. The blue jeep continues to follow him everywhere and the unknown text messages persist: I'm watching you. I can see you. Dead bodies turn up and keep coming: mutilated bodies, bodies dissolved in acid, bodies found in mass graves. Corpses entombed in cement and with missing hands. There are no deaths in "Imperial Bedrooms," just corpses, and this fact -- like the pubic hair stuck in "Less Than Zero" -- is suggestive. Things happen in Ellis novels like they happen in action movies: abruptly and without aftershocks. Characters react but they do not emote. In the place where feelings might be is instead that blank spot of ennui, a vacuum, the opposite of "baggage." This is not an attitude that can process death or suffering, but one that spots the corpse and moves on.

If "Less Than Zero" was a book that sped by and made no real impression on a reader, its sequel can be absorbed just as quickly. But it shouldn't be. "Imperial Bedrooms" is a book with pleasurable sentences and tensions; with pulpy twists and shivering scenarios. I suspect it will be an easy novel for detractors of the author to misread. But Ellis is not an easy ironist, and here he is not gratuitous. He asks us a question: What can you do with an artful book about spiritual zombies? Read it and weep.

Shares