"If there's one thing I hate, it's the movies," says Holden Caulfield. "Don't even mention them to me."

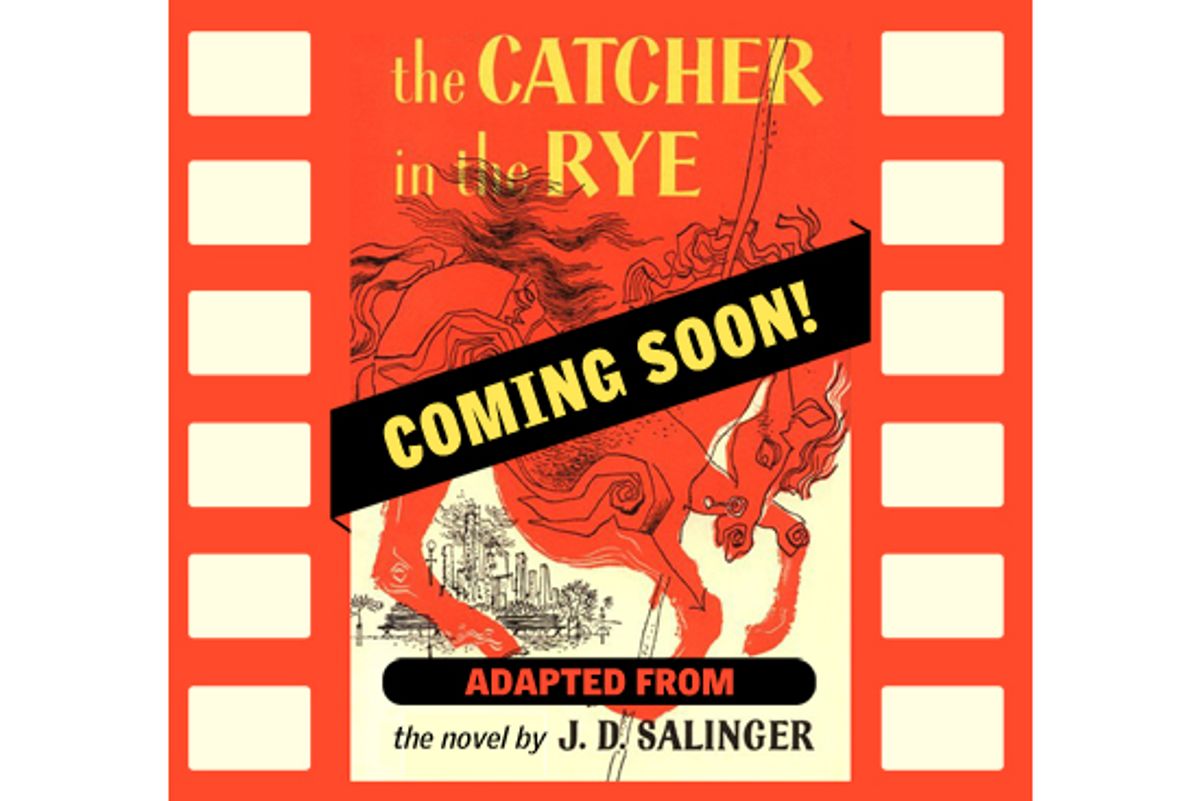

The young hero of J.D. Salinger's 1951 novel "The Catcher in the Rye" is often described as one of the great unreliable narrators in American fiction -- a character whose self-image is at odds with how he's seen by the rest of the world as well as his older, wiser creator. But when a Daily Telegraph story suggested that the late, reclusive writer's signature work might finally land on the big screen -- after decades of Salinger telling an endless parade of Hollywood phonies to take their movie pitches and shove them -- Holden's gripe struck me as a rare instance of a quote worth taking at face value.

A convergence of factors makes it likely that somehow, someday, there will be a movie. True, a lawyer for the Salinger estate said, "There are no plans to sell the film rights." But that only sounds definitive until you get to the part of the Telegraph story that says the writer's estate could be hit with a huge, retroactive estate tax bill that could be settled fast by auctioning the film rights to "Catcher" -- and that a 1957 letter by the author described those unsold rights as "a kind of insurance policy" that could support his wife and daughter if he ran out of money. When's the last time a lawyer won an argument with an accountant?

"The Catcher in the Rye" should never be made into a movie. Period.

To entertain such thoughts requires the would-be adapter to ignore three strong arguments against adaptation: Holden's opinion, Salinger's wishes and the reader's own idiosyncratic relationship with the novel.

Holden's likely position is there in black-and-white, so let's move on to Salinger's -- but not for long, because there isn't much difference, really. The novelist hated Hollywood as intensely as Holden did and spent years rebuffing anyone and everyone who tried to sweet-talk him into giving up the rights. Samuel Goldwyn, Jerry Lewis, Harvey Weinstein, Steven Spielberg and others all came courting and were rebuffed.

The writer famously said the novel was "unactable" by anyone but himself (he briefly considered letting Elia Kazan turn it into a play, then changed his mind). And he held a grudge against the American film industry for all sorts of reasons, including his busted relationship with Eugene O'Neill's daughter, Oona (who ultimately married Charlie Chaplin), and a previous negative experience with adaptation (Salinger's 1948 short story "Uncle Wiggily in Connecticut" was the basis for 1949's "My Foolish Heart," which he hated).

I realize Holden qualifies his hatred in "Catcher" by conceding there are good movies and bad movies and that his beloved kid sister Phoebe has a knack for identifying the good ones. I also realize everyone has a favorite book that they would rather not see turned into a film, and when filmmakers adapt it anyway, the result can sometimes be good, sometimes great. (Telegraph writer Harry Mount encouraged such thinking in a column suggesting "Catcher" could work on-screen if the filmmakers relied on voice-over narration drawn from Salinger's text.) And it's true that there are more examples of novels that were adapted to film against the author's wishes (during or after the writer's lifetime) and turned out rather well.

But "Catcher" is a special case, because Salinger specifically and repeatedly said the film should not be adapted and never gave anyone the chance -- and his stubbornness meant that several generations of readers treated the book as a unique experience, a book that would only ever be a book. Knowing Salinger's opinion on this matter only amplifies the experience of reading "Catcher" -- makes it more personal. You may see a movie in your mind as you turn the pages, but it's your movie, and it's playing for an audience of one.

That all means that if some intrepid person did persevere and somehow manage to make a "Catcher" movie, it wouldn't matter how good it was, because on some level, we'd all know its very existence rebuked what Salinger stood for. Even if it turned out to be a finely wrought adaptation of a classic novel, it would still feel like an act of petty dominance over a man who could no longer fight back, and an act of vandalism on par with another famous scene in Salinger's book, the one where Holden sees that someone has written "fuck you" on a school wall and rubs it off:

"You can't ever find a place that's nice and peaceful, because there isn't any," Holden says. "You may think there is, but once you get there, when you're not looking, somebody'll sneak up and write 'Fuck you' right under your nose. I think, even, if I ever die, and they stick me in a cemetery, and I have a tombstone and all, it'll say 'Holden Caulfield' on it, and then what year I was born and what year I died, and then right under that it'll say 'Fuck you.' I'm positive."

Shares