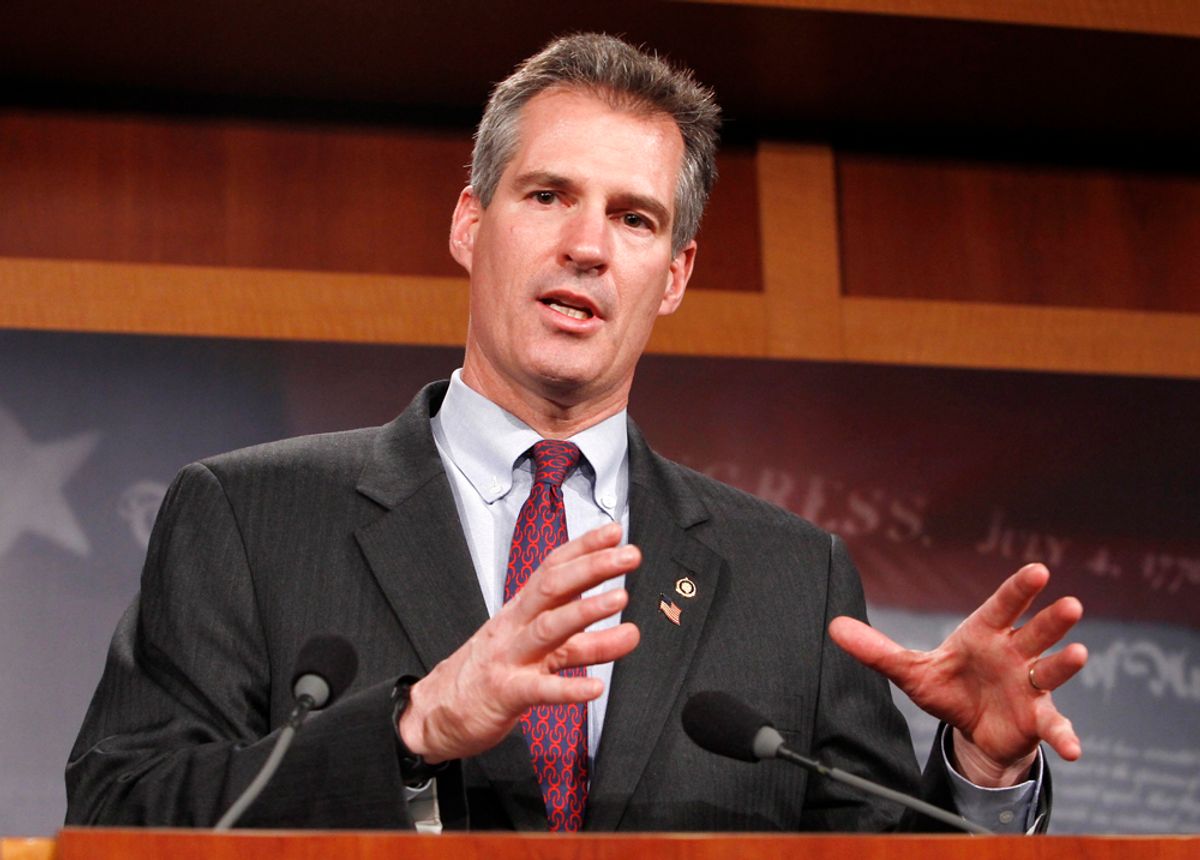

Consider the twisted irony that is Scott Brown, the Republican junior senator from Massachusetts. His upset election to replace the late Ted Kennedy on Jan. 19 shocked the White House -- and prompted immediate action. Just two days later, President Obama endorsed the "Volcker rule" -- a proposal by former Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker to restrict banks from running hedge funds and making proprietary trades on their own behalf. Though almost universally seen, initially, as a purely political reaction to an embarrassing defeat, the Volcker rule defied conventional cynicism and ended up being incorporated into the version of bank reform passed by the Senate.

But its ultimate strength, in flux Thursday afternoon as the conference committee reconciling the House and Senate bank reform bills hammered out the last details of the law, now hinges on none other than Scott Brown. In fact, the Senate might never have gotten the crucial 60 votes to pass cloture on its version, if Brown had not been promised that his "concerns" about the Volcker bill would be addressed. If that paradox -- the man whose election inspired the Volcker rule holding its ultimate fate in his hands -- doesn't sum up the craziness of the final moments of bank reform negotations, nothing does. A senator sworn in five months ago owns the swing vote on the most important financial reform legislation in decades.

Brown's concerns are strictly parochial. On the one hand, he wants mutual funds and insurance companies exempted from the Volcker rule. Not uncoincidentally, such exemptions would apply to major Massachusetts-based financial institutions such as Fidelity and MassMutual.

But Brown is also carrying water for another Massachusetts big boy, State Street, the 19th largest bank in the U.S. State Street is worried that the Volcker rule will prevent it from investing money in its own stock and mutual funds, which represent a considerable part of its business. The Volcker rule, in his original formulation, would have strictly prohibited any bank that relied on federal insurance or access to discounted credit from the Federal Reserve to invest in proprietary trading. Brown introduced an amendment to the bank reform bill that would allow banks to invest as much as 5 percent of their capital. The latest reports from Washington indicate that negotiators are currently settling on 2 percent of capital as the upper limit.

You can make a very good case that even 2 percent is too high. Exhibit A: State Street, which was guilty of investing very small portions of its own capital in off-balance sheet special investment vehicles that blew up during the financial crisis and required a $2 billion bailout from the government. State Street, in fact, is a case study for why a strong implementation of the Volcker bill is necessary.

American Banker is reporting this morning that Scott Brown won't get his exemptions, and that the Volcker Rule is actually likely to be strengthened rather than weakened during Thursday's negotiations. (Even more irony: The Volcker rule may be pumped up as part of a deal to gut Blanche Lincoln's derivatives regulations.) Does that mean Brown would jump ship? My guess is it isn't likely. Despite Brown's propensity for declaring that he is the all-important "deciding vote," there is still plenty of question as to whether a Massachusetts senator would have any political future if he was seen as the man who torpedoed bank reform.

We'll know more as the day progresses, but in the meantime, here's bank reform in a nutshell: The man whose election prompted a stronger push for tougher bank reform is busily working to shield a bank that made exactly the mistakes bank reform is supposed to prevent from the restrictions the law seeks to impose.

Shares