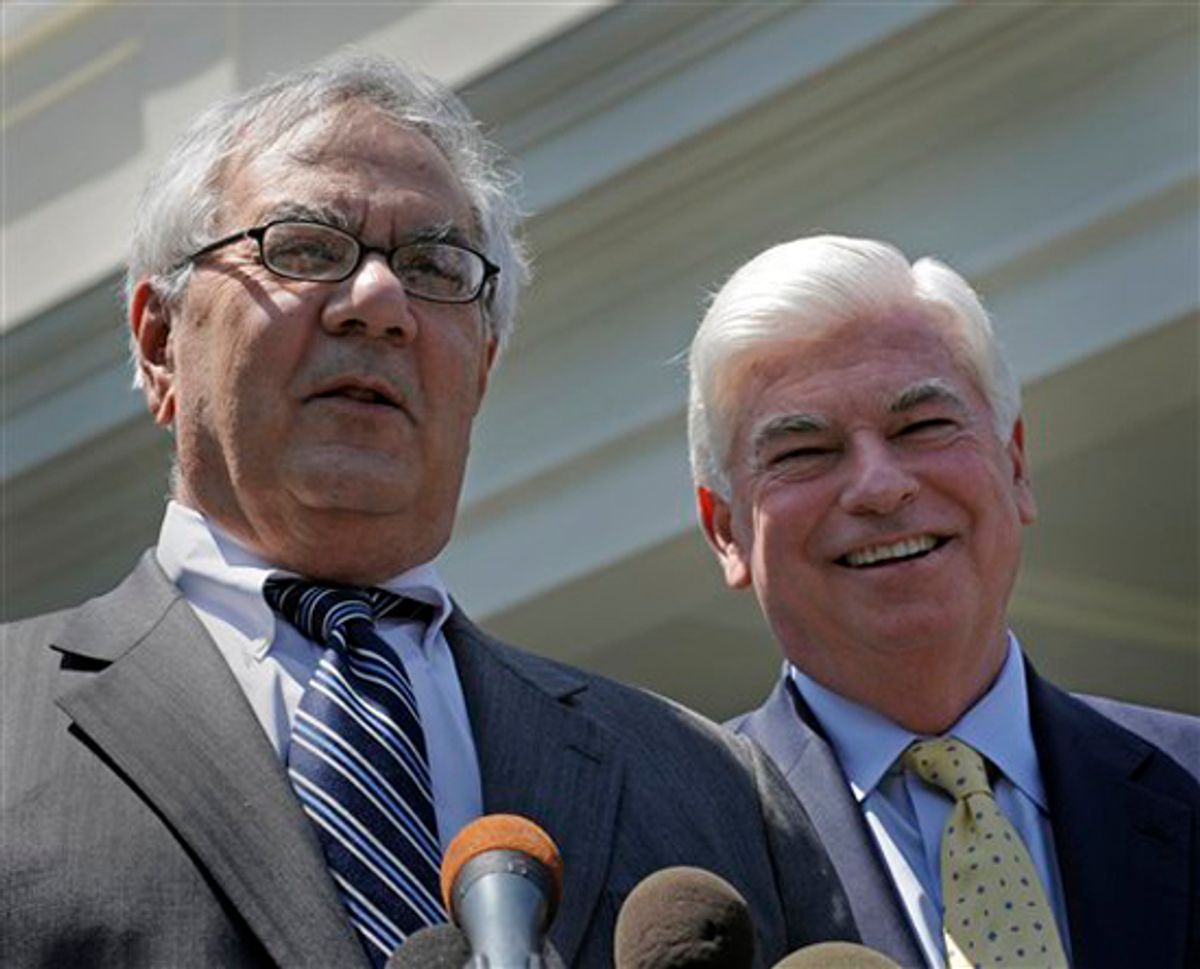

Now that the newly dubbed "Dodd-Frank" bank reform bill is all but complete -- awaiting President Obama's signature, possibly on July 4 -- what are we supposed to think? Is it a good bill? Will it rein in the financial sector? Will the words "Dodd-Frank" ring through the history with the same awesome knell as "Glass-Steagall"?

Let's start with the easy question first. Dodd-Frank is no Glass-Steagall. Glass-Steagall separated commercial and investment banking with one stroke of a giant Chinese meat cleaver -- no ambiguity allowed. Dodd-Frank is the polar opposite, a concatenation of intricate compromises tied up in 2,000 pages of complexity so dense that it willfully defies comprehension. Maybe the most optimistic way to think of this bill is as a stimulus program to create jobs for securities lawyers -- they'll be chewing on it for decades to come.

Before getting into the details, it's probably safe to say that one's position on the bill's worth largely depends on one's starting point. If you are a progressive who believes that the only real solution to Wall Street's disproportionate ability to screw up the economy is to break up the big banks, then you will be disappointed, and scathing in your criticism. If you are a conservative who, despite the evidence of the last few years, still believes that regulation, ipso facto, is bad, bad, bad, you will also be critical. Every single Republican from the House and the Senate serving on the conference committee voted against the final deal.

If you live in the murky middle, where you recognize that, given the constraints on how our government currently works, incremental progress is the best one can hope for -- on any front -- then, maybe, there are some reasons for guarded optimism. There are indisputably good things in this bill.

- There is a reasonably independent consumer financial protection agency. Yes, it was shamefully gutted by a carveout insulating auto dealers from oversight, but it is still an improvement on what existed before. Put consumer advocate crusader Elizabeth Warren in charge, and watch the financial industry quail!

- The ability of credit card companies to gouge merchants with "swipe fees" every time a customer used a debit card is significantly restricted. This was a surprise -- few people predicted that the bank reform bill would take a swing at this long festering problem.

- There are new limitations on the amount of proprietary trading banks can do on their own behalf -- the so-called Volcker rule.

- There is increased federal oversight of derivatives regulation, and the big banks face new prohibitions on some forms of derivatives trading.

The last two items deserve a closer look. There is no question that both the Volcker rule and Blanche Lincoln's original derivatives reform proposal -- that banks be required to spin off all their derivatives trading operations -- have been significantly watered down. But it is worth remembering that when both of these proposals were originally announced, the universal reaction was that they did not have a chance in hell of getting passed -- they were far too strict. Republicans and moderate Democrats alike were highly dubious. The banking lobby fought ferociously to eliminate them entirely. But Wall Street only succeeded in weakening the reforms. Again, in today's political climate, that counts for success!

This is more true for the Volcker rule than derivatives reform, however.

The consensus of reform watchers is that at the very end, the Volcker rule was both strengthened and weakened. Strengthened in the sense that there is no discretion involved; banks now face rigid limits in the percentage of their total capital that they can invest in hedge funds or private equity funds. Weakened in the sense that the original Volcker rule called for a complete ban on proprietary trading. But the final compromise allows banks to invest up to 3 percent of their capital in such funds.

Critics are right to warn that a lot of damage can still be done in such a scenario, but the bottom line is this: Risk and the potential for excessive bank profits have both been constrained.

Derivatives is a much more dicey case. Blanche Lincoln's proposal would have forced the banks to spin off all their derivatives trading. The compromise reached after some 20 hours of wrangling, in the wee hours of Friday morning, supposedly requires banks to spin off only the riskiest derivatives trades -- including, theoretically, the notorious credit default swaps that sunk A.I.G.

Congressional Quarterly (pointed to by the indefatigable David Dayen at FireDogLake) has the best description of the deal.

Under the derivatives compromise, banks will be able to keep their business in derivatives tied to interest rate swaps, which represent a huge swath of the market. Banks would also be permitted to continue to trade in derivatives related to foreign exchange swaps, credit, gold and silver, investment-grade credit default swaps and any transaction used to hedge risk.

Financial institutions will need to divert derivatives related to commodities, energy, metals, agriculture, equities and below-investment-grade credit default swaps into a separately capitalized entity walled off from federally insured deposits.

Any credit default swaps -- a type of derivative linked to the meltdown of insurance giant AIG -- remaining in the bank would go through a central clearinghouse. A clearinghouse acts as a neutral third-party that guarantees a derivatives trade.

Getting all credit default swaps traded through central clearinghouses is a major achievement that should bring much more transparency to the dark underbelly of the market for credit derivatives. But the loopholes here are beyond enormous. As Dayen notes, "any transaction used to hedge risk" can and will be interpreted in all kinds of imaginative ways. The division between investment-grade and non-investment grade credit default swaps depends on judgments made by the credit rating agencies, which does not inspire confidence. And most of the actual derivatives rules incorporated in the Dodd-Frank bill have yet to be examined by anyone besides the people who wrote them. There are undoubtedly unpleasant surprises yet to come.

But to interpret this compromise as a failure of nerve by Blanche Lincoln is unfair. When even Nancy Pelosi is arguing that the votes aren't there -- then the votes aren't there. Lincoln never had a chance to get her proposal into law, intact. A lethal combination of New York Democrats doing the bidding of their most important constituent -- Wall Street -- and Blue Dogs was too much to overcome. What we have ended up with is as good as it gets, for now.

Dodd-Frank is no Glass-Steagall, but the combination of the modified Volcker rule and the derivatives compromise do add up to a serious change in how Wall Street will be doing business. The Wall Street Journal opines that there is a "common thread: large financial companies are facing a tougher leash." Whether that leash is strong enough to prevent another mad dog rabies attack that infects the entire global economy is worth questioning. If it is true, as the New York Times quoted the president saying, "that the bill contained '90 percent of what I proposed when I started this fight,'" then Obama probably proposed far too little. Maybe it would have been better to push for twice as much and only get 75 percent of what he asked for.

But that's the narrative of our time. Achieving sweeping change, whether in healthcare, or bank reform, or energy, is effectively impossible, given the rules that govern the Senate and the fierce obstructionism of the Republican Party. Achieving anything at all in this context is still an astonishing victory.

Shares