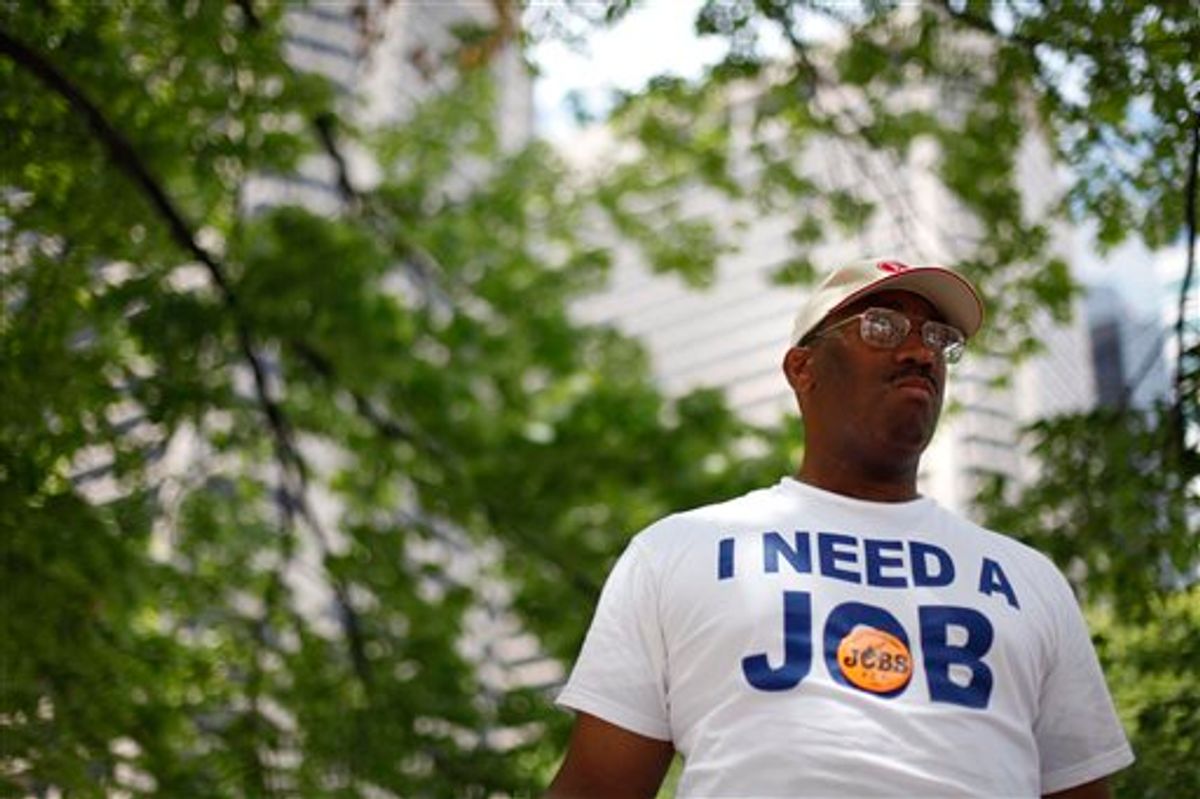

As measured by the number of Americans facing persistent, long-term unemployment, the United States is currently struggling through the worst labor market since the end of World War II.

"Of the 15 million unemployed in America," writes Annie Lowrey in the Washington Independent, "over 7 million have been out of work for more than six months, nearly 5 million for a year and over 1 million for two years -- the worst statistics since the government started keeping count in 1948. The proportion of the unemployed out of work for more than six months has doubled in the past year, to more than 46 percent."

To most Americans, those are discouraging numbers. But Bloomberg's Steve Matthews finds a remarkable silver lining.

The 6.8 million Americans out of work for 27 weeks or longer -- a record 46 percent of all the unemployed -- are providing U.S. companies with an eager, skilled and cheap labor pool. This is allowing businesses to retool their workforces, boosting efficiency and profits following the deepest recession since the 1930s, and contributing to a 61 percent rise in the Standard & Poor's 500 Index since March 2009.

"Companies are getting higher-productivity employees for the same or lower wage rate they were paying a marginal employee," said James Paulsen, who helps oversee about $375 billion as chief investment strategist at Wells Capital Management in Minneapolis. "Not only are employees higher skilled, you have a better skill match. You have a more productive and more adaptive labor force."

Am I wrong to hear an all-too-familiar tone of "let-them-eat-cake" in this don't-worry-be-eager-skilled-and-cheap message from the owners of capital? Long-term unemployment is well known to have a devastating financial and psychological impact on actual human beings. But if the result is higher productivity for businesses, who cares if the social fabric is rent in tatters?

But wait, there's more! Another silver lining: The U.S. recession is making American multinational companies more competitive with their foreign counterparts.

The lack of wage pressure also "reinforces the case for globally exposed companies" because "there has been better cost containment in the U.S. than in some of our competitors," said Ethan Harris, head of North America economics at Bank of America-Merrill Lynch Global Research in New York. He said this would benefit businesses such as Cincinnati-based Procter & Gamble Co., the world's largest consumer-products company, and Atlanta-based Coca-Cola Co., the world's biggest soda maker.

You can hear echoes of this in the latest news on the Foxconn-Apple-suicidal workers saga. The Financial Times reports that after Apple resisted Foxconn's attempts to pass on recently instituted wage increases to its single biggest customer, China's largest employer is now pushing to move its assembly lines deeper into China's hinterlands, where wages are lower.

This is a welcome development for workers in China's less developed regions. They will no longer be forced to migrate as far from their homes and families to find decent paying jobs, and the trend will help alleviate the huge income inequality between coastal and inland China. But what does Apple's reluctance to accept Foxconn's wage hikes say for the values dominating current U.S. economic discourse?

Apple is of course in no way exceptional in seeking every opportunity to contain labor costs. As the Bloomberg story indicates, from the point of view of capital, mass unemployment is a feature, not a bug, a chance for employers to cherry-pick quality employees at bargain prices. Hey, if it gets too expensive in rural China, Foxconn can just set up shop in South Carolina!

How far we've come from the days of Henry Ford, who gave his workers wage increases so that they could afford to buy Ford's cars. Just how sustainable are corporate profits that are predicated on squeezing workers, if the end result is a working class that can't afford to buy anything? Income inequality was a growing problem in the United States before the Great Recession -- all signs now indicate that society will be even more stratified as we fight our way toward something that resembles an economic "recovery."

Shares