The Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University is renowned for its all-star faculty and an alumni roster that reads like the guest list at the G-20 summit. But just because a school has impressive names doesn’t mean that it’s an impressive school. The "mid-career" program that serves its most august graduates -- people like Ban Ki-moon, Felipe Calderón, and Paul Volcker -- is, despite an impeccable pedigree, a cash cow that grants degrees for attending what is essentially a year-long networking event.

Nothing demonstrates this better than the recent revelation that “Donald Heathfield,” one of the accused Russian spies rounded up earlier this week, attended the Kennedy School’s mid-career program from 1999 to 2000. The question isn’t why Harvard let in a man who turned out to be an alleged spy. Almost everyone who met Heathfield mistook him for a perfectly legitimate Canadian businessman, and there’s no way the school could have known otherwise. The question, rather, is why the Kennedy School of Government, alma mater of everyone from Pierre Trudeau and Andrew Card to Katherine Harris and Joe Sestak, would let in a man without any significant qualifications beyond the ability to pay. And the question is especially relevant given that Heathfield seems to have used his Kennedy connections to draw himself worrisomely close to the kinds of powerful individuals that could provide him with the classified information he needed.

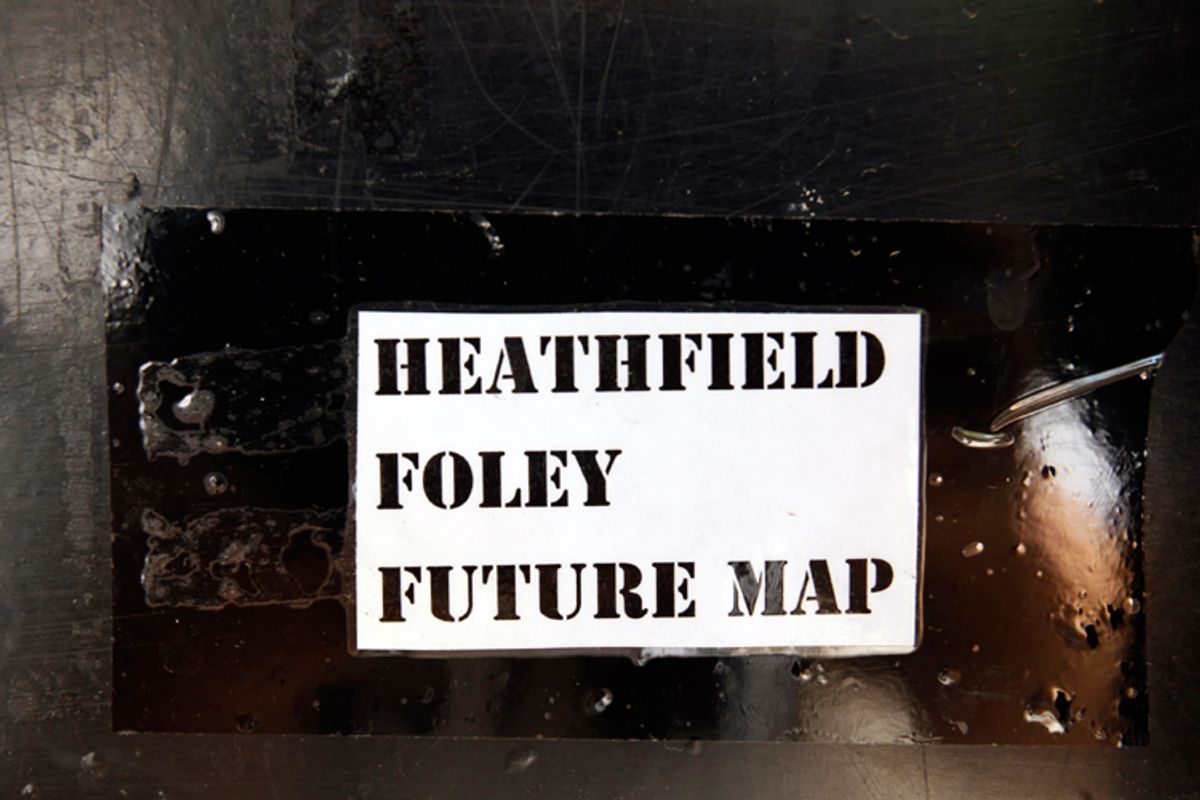

Healthfield’s current resumé is undeniably impressive. It includes a position at the consulting firm Global Partners and the invention of forecasting software FutureMap. The problem is that these both post-date (and were, most likely, the result of) his Kennedy School degree, which he received in 2000. According to his Linkedin profile, Healthfield joined Global Partners in 2000 and started FutureMap in 2006. Moreover, according to the FBI complaint, he arrived in America in 1999, most likely to attend school, so it’s unlikely he would have had any domestic achievements at the time he applied. His only pre-Kennedy qualifications seem to be educational. York University in Toronto confirmed he received a BA there in 1995, which would line up with the Canadian source of his stolen identity. He also claimed to have received degrees from the École Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées in Paris and the London School of Economics, though neither institution has yet indicated whether this is the case. These are not bad schools, certainly. But it doesn’t exactly make him a candidate on the level of Paul Volcker. To be fair, it’s unclear what else Heathfield may have said on his application, and as a spy, presumably he could have been convincing enough to get past a rigorous screening process. But this lack of rigor is precisely the problem with mid-career MPA (Master of Public Administration) and MPP (Master of Public Policy) programs such as the one offered by the Kennedy School.

While the two-year pre-professional master’s programs in public policy are generally regarded as invaluable career preparation for those wanting to work in government, the one-year mid-career programs are more like cash cows, attracting older students with established careers who are drawn to the name. This distinction may be difficult to discern from the outside -- certainly combining the words “Harvard” and “Kennedy” on your resuméwould make anyone seem qualified -- but it’s a crucial difference. The former is an actual, hard-earned Master’s degree, while the latter is more a certificate of participation, an indulgence the politically-minded can purchase to crown their glory.

The Kennedy School insists otherwise, describing its mid-career program as being "designed to increase the knowledge and skills of well established, high-performing professionals, who seek to enhance their public service careers or to move from the private sector to a leadership position in either the public or non-profit sectors." And certainly, schools that offer these programs are not entirely at fault. The mid-career programs can fund many other activities, and when you attract the kind of hyper-impressive students the Kennedy School does, it’s unclear how much these older, established leaders are willing to be taught anyway. But this doesn’t take away from the fact that supposedly academic programs are, in reality, no different from a political schmoozefest, where, instead of learning the innovative policy and management ideas that might actually make them better leaders, influential figures from across the globe are given the opportunity to meet privately before they have to deal with each other professionally.

Certainly this is what Heathfield used Kennedy for. As the New York Times reports, he networked aggressively, organizing bar crawls for his fellow students and visiting international students in their home countries after graduation. It seems likely, given his lack of other credentials, that this aggressive networking is what landed him the consulting job at Global Partners, and which allowed him to start FutureMap.

This is all well and good. It’s maybe even the modern American dream. If it’s a bit questionable from a meritocritous angle, you can’t necessarily knock the hustle. The weird thing here is that this was a consciously-executed spy game. The whole idea behind Healthfield’s ten-year run in the States was to work his way into policy circles so he could gain access to influential people and eventually steal secrets. And while the latter part of the plan didn’t work (the FBI was on to the ring for years), the former part certainly did - his work at Global Partners put him in contact with experts on nuclear energy and other important policy areas. Through the vehicle of a take-all-comers mid-career policy program, Healthfield was able to gain access to the corridors of power without any particular qualifications.

Maybe the ultimate lesson here is that if he can do it, you can, too. Two years at the Kennedy School runs you a mere $157,362. If you can save up that much (or take out a loan), maybe you, too, can hobnob with the best and brightest the world has to offer.

Shares