Every city in the country, I suppose, has its own relationship with New York City -- you know, much the same way that every college basketball team in the old ACC had a rivalry with North Carolina. The City is just omnipresent in American life. Everyone knows about Boston's rivalry with New York and the friction between Philadelphia and New York and the long-distance relationship between Los Angeles and New York. Chicago calls itself "Second City"-- and while technically this is because of the way it rebuilt itself after the Great Chicago Fire, I know many people in Chicago who believe it is in some way a reference to New York and its entrenched role as the First City. Kansas City* has a chip on its shoulder about New York that goes back to before the days when the Kansas City Blues were a Yankees minor league team and before the Kansas City A's traded Roger Maris to the big city. People in towns big and small all across America have long placed their own city's charms and ease and little town blues against the madness they caught on that vacation when they saw "Cats," caught the Rockettes and nearly got killed three times in cab rides through the streets.

*One of my favorite pieces of art was a New Yorker cover from 1976 -- Saul Steinberg's view from 9th Avenue. If you click on the link, you will begin at 9th Avenue, then there's 10th, then the Hudson River, and then way beyond that is New Jersey and then the rest of the country -- with Kansas City in the middle. Then beyond that is the Pacific Ocean and China and Russia. I'm not certain if that really is the view of all New Yorkers -- but that is certainly the view Kansas Citians have of New Yorkers.

Cleveland's relationship with New York, though, always seemed just a little bit different to me, it always seemed that of a little brother or sister who wanted to wear the same clothes. Growing up, I can remember hearing about New York every week in one way or another. Someone would mention that, for many years, the Terminal Tower was the tallest building in America* ... you know, outside of New York. Playhouse Square was (and is) the second largest performance arts center ... after Lincoln Center in New York. There's a big fashion week in Cleveland, one of the biggest in the country, probably THE biggest outside of, well, New York. The Cleveland Orchestra has always been one of the best in America, right there with the New York Philharmonic. Little Italy in Cleveland had food about as good as you could find outside of Little Italy in New York. And I cannot even tell you how many times I heard growing up that the collection in the Cleveland Museum of Art was as good as anything you might see in New York City.

*It was actually the tallest building outside of New York until the year I was born, 1967. Then Chicago started building skyscrapers.

Yes, the New York comparisons were all-consuming, but the weird part is I just never felt the same bitterness from Cleveland toward New York. Sure, Clevelanders hate the Yankees because, well, you HAVE to hate the Yankees, it's a law. But beyond that, Cleveland always seemed perfectly content to be sort of a little New York, to have good things that were just about New York quality, to dream about moving to New York for a business deal someday.

It's not out of character that LeBron James, who grew up in Akron, is a Yankees fan and seems utterly fascinated by New York. There's something very real there. I remember when I was a kid, when everything in Cleveland was going to hell, there was a semi-bizarre tourism campaign to start calling Cleveland a "Plum." Radio and television commercials were played. Only it wasn't bizarre really -- it was another chance for the city to try and connect with New York. T-shirts were made: "New York may be the Big Apple but Cleveland's a Plum." I don't recall that the T-shirts sent Cleveland tourism skyrocketing, but I'm not sure it was the point. The point might have been to have a T-shirt with New York and Cleveland on it.

And it seems to me that the Cleveland-New York relationship is close to the heart of the story of George Steinbrenner. He grew up in Cleveland. And in a way I've always thought that defined him. He has to be the most famous New Yorker who never really lived in New York. It's the Cleveland in him.

------

The story of King George is fascinating to me because, at the end of the day, the story goes wherever the narrator wants it to go. Do you want a hero? Do you want a scoundrel? Do you want a tyrant? Do you want a heart of gold? Steinbrenner is what you make him. He is the convicted felon who quietly gave millions to charity, the ruthless boss who made sure his childhood heroes and friends stayed on the payroll, the twice-suspended owner who drove the game into a new era, the sore loser who won a lot, the sore winner who lost plenty, the haunted son who longed for the respect of his father, the attention hound who could not tolerate losing the spotlight, the money-throwing blowhard who saved the New York Yankees and sent them into despair and saved them again (in part by staying out of the way), the bully who demanded that his employees answer his every demand and the soft touch who would quietly pick up the phone and help some stranger he read about in the morning paper.

As Steinbrenner walks away from the New York Yankees -- and as rumors about his failing health grow louder -- everyone looks for his epitaph, for the few sentences that sum up his messy career. Is George Steinbrenner essentially good or bad, a Hall of Famer or a scourge on the game, a decent man who simply had to win, or a callous bully who showed a little decency in his spare time? The answer to all of that, I suspect, is "Yes."

He did grow up in Cleveland, son of a shipping magnate and a bit of a legend. He is George Michael Steinbrenner III, but his father was called Henry, and he was an NCAA hurdles champion while at MIT in 1927. There is something precise about hurdlers, and Henry Steinbrenner was a precise man. He demanded something like perfection from George, and George failed him time and again. He could not cut it at MIT. He could not become a world-class hurdler. He was sent off at 13 to military school.

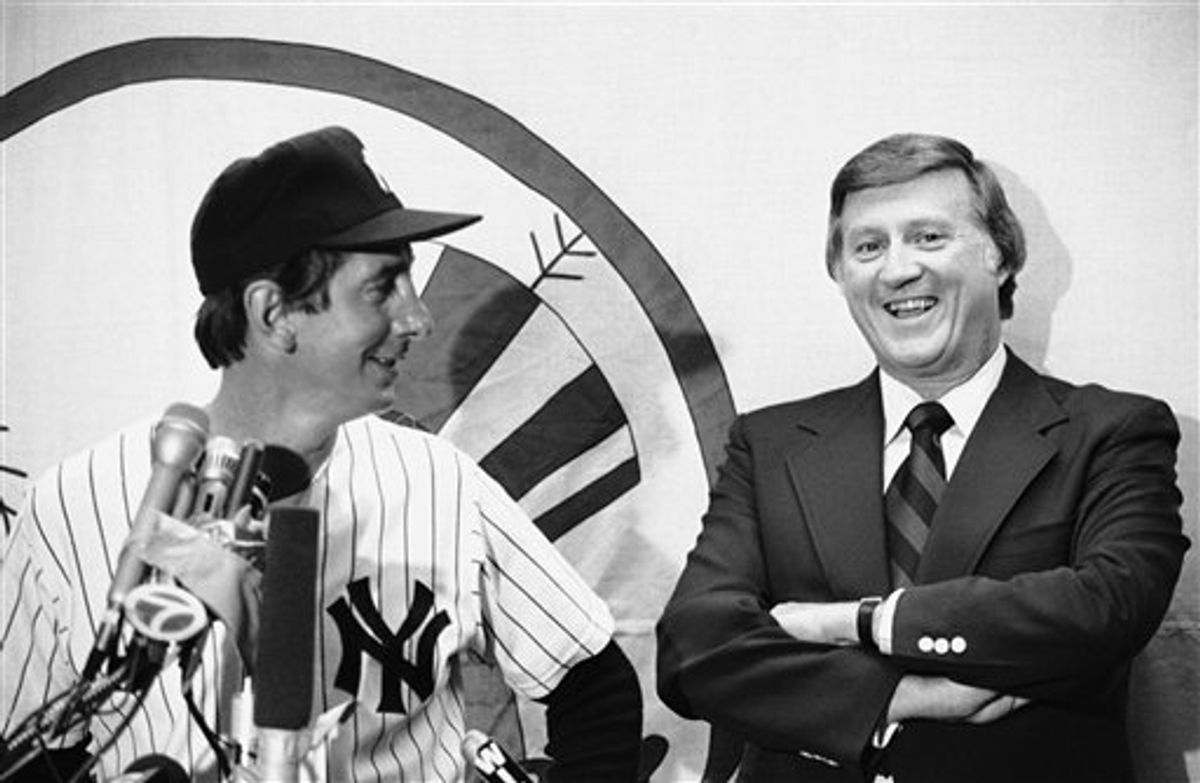

At different times in his life, George told the most famous story about his father differently -- most often, the story goes that when George put together the consortium to buy the New York Yankees in 1973 (putting in $168,000 of his own money), Henry told the newspapers it was the "first smart thing he's ever done." At other times, though, George says it wasn't until his Yankees actually reached the World Series in 1976 that Henry said, "It's the first smart thing he's ever done." Either way, it's clear Henry did not have much regard for his son's intelligence.

And George never hid from the idea that he was just a son trying to prove his worth to his old man. That's another funny part of the story: Nobody has spent more time psychoanalyzing George Steinbrenner than … George Steinbrenner. He has lived such a public life, and has come across so many opinions about himself ("If I believed half the things said about me, I wouldn't go home with myself," he has said), that he cannot help but develop his own theories about himself. He seems to believe that his father's hard distance is the key to his own story, the reason he has been so driven to win, the reason he has never been able to tolerate weakness or ineptness in others -- even if the weakness and ineptness were only imagined in his mind.

------

First, he tried to buy the Cleveland Indians. That was 1971, when the Indians were in so much trouble there were rumors that the team would begin playing roughly half its games in New Orleans, in a new domed stadium, beginning in 1974. Things were getting bad in Cleveland then, and Steinbrenner offered $6 million for a team that had been valued at about $8 million. Then he denied making any offer at all. Then when it looked like he would lose the bidding he brought in Cleveland Indians legend Al Rosen (the 1953 MVP) and pushed his offer to $9 million. Already, you could see the Steinbrenner mind at work, his reluctance to lose at anything. As it turned out, his final bid still wasn't enough -- Nick Mileti, who already owned the Cleveland Cavaliers and NHL Cleveland Barons, got a group together and offered $10 million, a foolish bid. Mileti, best I can tell, was already leveraged up to his eyeballs, and the Indians were a bad investment then. There is no guessing how much different baseball would have been in the 1970s and beyond had Steinbrenner bought the Indians.

Then, it's also true that the New York Yankees were hardly a bargain in the early 1970s. They were owned by CBS, and they were terrible in just about every way imaginable. In 1972, for the first time since the end of World War II, the Yankees drew fewer than a million. They had not won a pennant since '64, which was BY FAR the longest gap for the Yankees since the years before Babe Ruth. Truth is, things had become stale in the Bronx -- aging Ralph Houk was the manager, Mickey Mantle was retired, the Mets had won over the city, and it just seemed like the Yankees would never again be the Yankees.

Steinbrenner, though, saw it all differently, and I feel certain this was the Cleveland in him. He still saw the Yankees as the team he remembered from his childhood, the Yankees were still the Yankees of DiMaggio and Ruth and Gehrig. To him, New York was still New York, it was all so glamorous and thrilling and, yes, big time. "Coming to New York was like a different world," he told the New Yorker three decades later. "It was like, 'Whoa, look at the tall buildings!'"

He and his group paid $10 million for the Yankees -- though Steinbrenner has long said it was only $8.8 million because he sold some parking lots and land that came with the deal back to the city for $1.2 million -- and Steinbrenner famously said that he would stay in Cleveland and not be active in the day-to-day operations. People who knew Steinbrenner understood there was no chance of this -- but nobody in New York knew Steinbrenner then. They would very soon.

The Yankees were lousy again in 1973, and before that season got going, he fired president Mike Burke. At the end, he nodded when general manager Lee MacPhail became league president, he accepted Ralph Houk's resignation and he tried to steal Oakland manager Dick Williams away from A's owner Charlie Finley. By the end of that eventful year, he was also lying to the FBI about a scheme in his shipping company that was sending money to Richard Nixon's "Committee to Re-elect the President" -- the famous CREEP from "All the President's Men."*

*Steinbrenner would later be indicted on 14 counts of making illegal contributions and obstructing justice. The odd thing is that Steinbrenner was neither a Republican nor a particularly strong supporter of Nixon -- his closest political friend at that time was probably Ted Kennedy and he raised millions more for Democrats than Republicans. No, the contributions were not about politics, they were about business. He was lobbying against restrictions in the shipping business, and Nixon was obviously the man in charge. Steinbrenner pleaded guilty to one felony count of obstructing justice, was fined $15,000 and was suspended by baseball for 15 months. Because of the felony conviction, Steinbrenner was not allowed to vote until 1989, when Ronald Reagan pardoned him in exchange for Steinbrenner admitting to the crime.

Point is that by 1974, Steinbrenner was already Steinbrenner, fully formed, fully obsessed, fully determined to be a star. "Although I was born in Cleveland, I can remember as a boy how much appeal the Yankees always had," he told Milt Richman at UPI. "They are important to New York and the whole nation."

He talked about how he had seen "Pride of the Yankees" at least 15 times.

In early 1975, with Steinbrenner serving his suspension, the Yankees spent millions to steal Catfish Hunter away from Oakland -- a move that changed the landscape of baseball. In June, while still on suspension, Steinbrenner and Charlie Finley tried to get Bowie Kuhn thrown out of office. In August, while still on suspension, the Yankees fired manager Bill Virdon and hired a pit bull named Billy Martin, leading the great columnist Red Smith to write this classic droll lead: "A fellow can't help wondering how George Steinbrenner will react when he comes back to the Yankees and discovers that Gabe Paul has fired his manager-of-the-year behind his back and hired somebody else's manager-of-the-year."

Well, George could not help himself. He never could help himself. "George is an overbearing, arbitrary, arrogant SOB," his longtime friend and Cleveland businessman C.L. Smythe told reporters. "There's no denying that. But I just love him. "That from one of his best friends.

------

Steinbrenner never stopped telling people about the importance of the New York Yankees. It was that word: Importance. Steinbrenner always loved axioms, sayings, quotations, a few collected words that speak to the larger truth. He can quote a hundred of them -- and in virtually every interview he will quote at least a half dozen. Plutarch said that the measure of a man is in the way he bears up under misfortune. Ralph Waldo Emerson said, "Do not go where the path may lead; go instead where there is no path and leave a trail." John Wesley said, "Cleanliness is next to Godliness." Shakespeare, through Polonius (in "Hamlet"), said, "To thine own self be true." And so on -- Steinbrenner never tires of memorizing these quotes. It seems to be how his mind works … he sees things as IMPORTANT and SWEEPING and SIGNIFICANT and HISTORIC. It's probably the old football coach in him -- Steinbrenner for a time was a graduate assistant under Woody Hayes at Ohio State, and he served as a full-time assistant at Northwestern and Purdue in the '50s. And with football coaches, every game is for world domination.

Point is, Steinbrenner has never been much for the tedium of the everyday, no, he needed constant victories in his life, he needed perpetual action in his life, he needed to believe there was something momentous going on. He never saw the Yankees as a baseball team or even THE baseball team. No, he saw the Yankees as the American way of life. He expected his players to be clean-shaven, he made sure patriotic songs like "Yankee Doodle Boy" were played at games, he had his legendary announcer Bob Sheppard talk endlessly about the "Yankee Way." When a player turned down his money, Steinbrenner saw that as a failing in the player's character, a sign that the player did not have the right stuff to wear the pinstripes and be a New York Yankee. To be against the Yankees, in the mind of George Steinbrenner, was to be anti-American.

That attitude seeped into everything. When the Yankees lost, Steinbrenner did not just see it as a loss, he saw it as an affront, a sign that someone was not living up to the Yankee Way, someone had failed the team, the city and, yes, America too. You better believe he had 16 managers from 1979 to 1995*. The Yankees weren't winning. Somebody had to pay. Somebody had to suffer. "Do your job or you will be gone," Steinbrenner said to someone pretty much every day; Steve Jacobson in his hard-hitting Newsday column reminded everyone that Steinbrenner had fired an electrician when the loudspeaker malfunctioned and fired a secretary for bringing the wrong sandwiches. You live up to his impossibly perfect image of the New York Yankees or Steinbrenner would exact retribution. Joe Torre went to the playoff every year from 1996 to 2007. They won four World Series. But did they Yankees win every game? No. Did they win every World Series? No. Every year, there was tension and rumors that Torre was finally gone.

*Not 16 DIFFERENT managers -- Bob Lemon, Billy Martin and Gene Michael kept reappearing in the early 1980s.

Of course, at the same time Steinbrenner punished himself too. He poured his baseball profits back into the ball club, sometimes foolishly, sometimes recklessly, but always with the unmistakable intent of winning championships and glorifying the New York Yankees (and if he got a little credit along the way, well, why not?). Sure, it is true that the Yankees made more money than any other team -- hundreds of millions per year more than some small-market teams -- but Steinbrenner did not have to spend so much of it on baseball. Only he did. In the 1980s, when the Yankees were floundering, he had to get every washed-up Ron Kittle, Mike Easler, Jack Clark, John Candelaria, Rich Dotson, Jesse Barfield, Claudell Washington and Andy Hawkins. Then, after he was suspended by baseball for a second time and the Yankees became the most dominant team in baseball, he STILL had to get Roger Clemens and Mike Mussina and A-Rod and Jason Giambi and Hideki Matsui and Gary Sheffield and any other superstar who might help the Yankees win every game one season.

There are different theories about how much the second suspension was responsible for the 1990s Yankees dynasty. In the late 1980s, Steinbrenner paid gambler Howard Spira (usually referred to as "shifty gambler" or "scheming gambler" or "small-time gambler" in the various newspaper stories) to give up some incriminating information on outfielder Dave Winfield. Steinbrenner felt like he had been cheated by Winfield and his agent, who had put a stipulation in the contract that ended up costing Steinbrenner a lot more money than he expected. Anyway, Steinbrenner had never forgiven Winfield for going one-for-22 in the 1981 World Series. He lashed out in the most vicious way, and he got suspended. The general consensus seems to be that his suspension gave the Yankees the freedom to let their own players develop, and those young players -- Derek Jeter, Jorge Posada, Mariano Rivera, Andy Pettitte, Bernie Williams -- were the nucleus of the reborn New York Yankees.

This is true, though I don't think it's the whole story. King George's money was still good around baseball. Plenty of multimillion-dollar signings -- David Cone, Chuck Knoblauch, David Wells, Roger Clemens, Hideki Irabu, David Justice, Jimmy Key, Kenny Rogers, John Wetteland and others -- played real roles on those World Series teams. The lovable 1996 Yankees, the team that supposedly represented a new way for the Yankees to do business, still had by far the highest payroll in baseball, a payroll that was 10 percent more than the Baltimore Orioles, a payroll twice the league average and three times larger the bottom six or seven teams. By 2000, the last year of the World Series dominance, the Yankees had the first $100 million payroll in baseball history -- and they rushed right by that to $113 million. The Yankees may have been smarter then, and they have been a bit more reserved, but the idea that George had learned restraint or that the Yankees were somehow fundamentally different seems a bit off. Steinbrenner was still out there, still spending, still promoting life, liberty and the Yankee Way. He still could not help himself.

------

There's a wonderful three-word expression that is often used when talking about George Steinbrenner. The expression is: "Nobody can deny." Think how often you hear those words put in front of a Steinbrenner trait. Nobody can deny that George wants to win. Or: Nobody can deny that he has done a lot of good things for people. Or: Nobody can deny that he was a terrible boss. Or: Nobody can deny that he made the Yankees the dominant team again. And so on.

I love that expression because, really, it doesn't mean anything. If nobody can deny it, why even bring it up in the first place? You wouldn't say, "Nobody can deny that the Magna Carta was issued in 1215" or "Nobody can deny that Jonas Salk developed the polio vaccine." That doesn't go anywhere. The reason it is so effective with Steinbrenner is because, honestly, every single thing about him is deniable. Good guy? Deniable. Bad guy? Deniable. Man who made the Yankees great? Deniable. Man who should have been given a lifelong ban? Deniable.

You can deny anything when it comes to George M. Steinbrenner III -- even hard facts. That's because he really has been one of a kind. You know how at the end of certain movies the screen will go blank and then words will appear, words that tell you how the story REALLY ended up -- like at the end of "Walk the Line," it said: "John and June were married in 1968. In fall of 1969, John sold 250,000 copies per month of his Folsom Prison and San Quentin albums, more than any other artist including the Beatles … John and June shared their artistry, compassion, wisdom, humor, lives and love with the entire world."

Well, what words could you put at the end of George Steinbrenner's movie? I've read a bunch of columns and stories about the man -- some of which make him out to be a hero, some of which make him out to be a bum, some of which make him out to be a complicated character, some of which make him out to be as predictable as San Diego weather. I've enjoyed all of them, because it seems to me they all have truth. He IS the "Seinfeld" character. He IS the humanitarian. He IS the felon. He IS the driven perfectionist. He fits every theory.

My theory is simply this: Steinbrenner is a Cleveland man who wanted to be a star. Cleveland has always been filled with those people. Steinbrenner needed parades, he needed fireworks, he needed something to be remembered by. You may know the story of King Mausollos, whose reign has been somewhat forgotten, but whose large tomb was one of the seven wonders of the world (and the inspiration for the word "mausoleum"). There are men and women who come along who simply need to be stars. And whatever else, Steinbrenner was a star. Nobody can deny that.

Joe Posnanski writes for Sports Illustrated.

Shares