In Chicago at the moment, if one were to look at the city through the prism of its police department, it would appear that someone's yanked a loose thread, causing the city to unravel. Last month in a courtroom downtown, Jon Burge, a former police commander, was found guilty of perjury, for lying about having tortured scores of suspects over a 20-year period in the 1970s and '80s. He was accused of using such interrogation methods as suffocating suspects with plastic typewriter covers, shocking others using a hand-cranked generator, and inserting loaded revolvers into the mouths of the accused. Six weeks ago, in a stable, middle-class South Side neighborhood, Thomas Wortham IV was shot and killed as four men tried to steal his motorcycle. Wortham, who was 30, had served two tours of duty in Iraq and was a highly respected Chicago police officer. In the days preceding his murder, he'd rallied his neighbors as they tried to reclaim the local park from thugs who'd been shooting each other on the basketball court. And a few weeks earlier, as police Superintendent Jody Weis held a press conference in a hardscrabble neighborhood to address the scourge of shootings (the city's homicide rate is up again), shots rang out. A youngster was shot two blocks away, underscoring the ubiquitous nature of the city's violence.

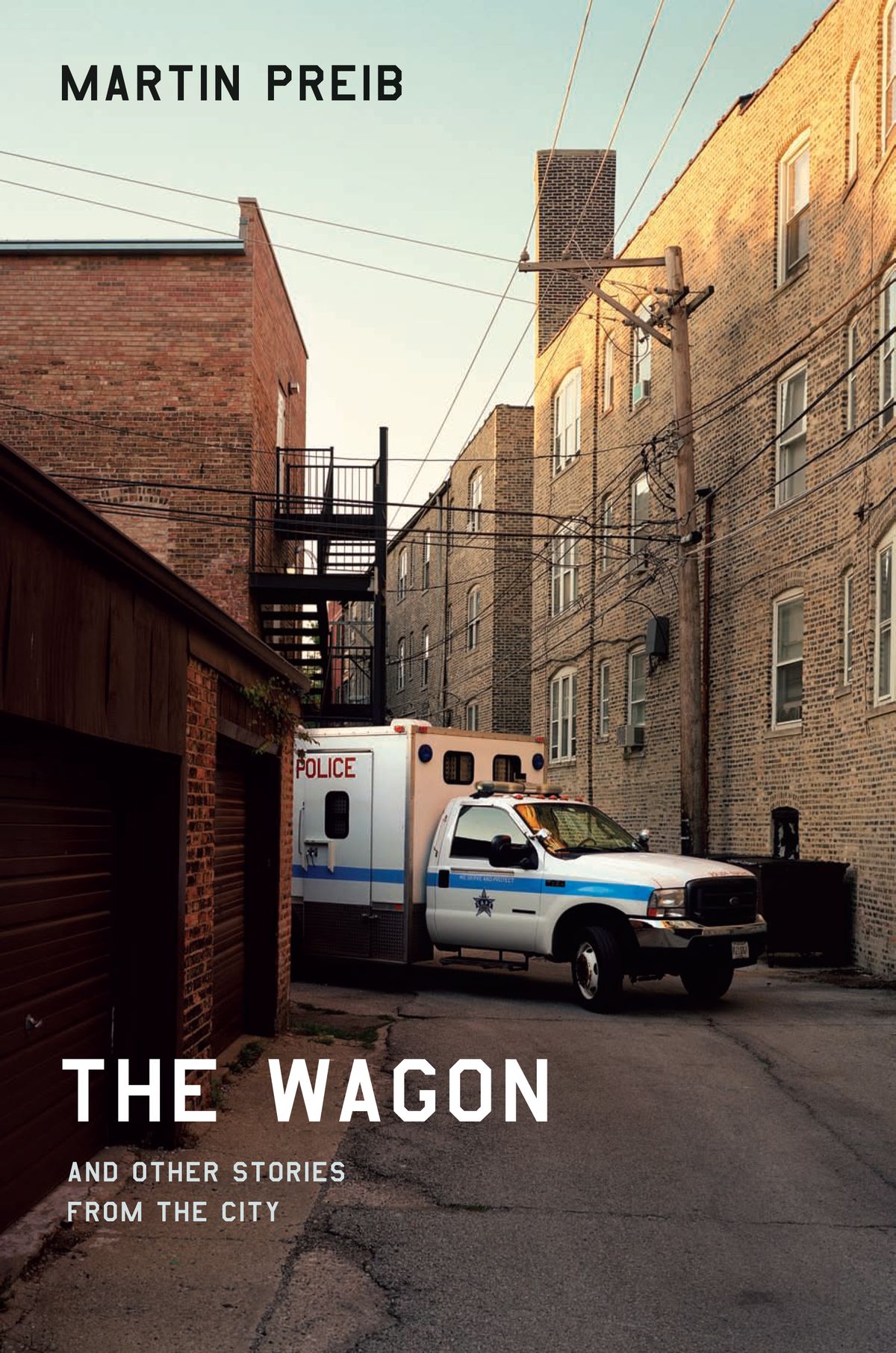

These incidents speak to the bravery, the occasional dishonor, and the outright frustration of the city's police. In the wake of all this, Martin Preib's "The Wagon and Other Stories From the City" is a welcome, albeit at times maddening, effort to fashion a narrative that reflects the reality of this messy, yet vital American city. Preib has been a Chicago cop for eight years, but he's not defined by his police work. He greatly admires Walt Whitman and William Kennedy, writers who despite having seen the worst in mankind were (in the case of Kennedy, still is) capable of maintaining a faith -- admittedly quivering at times -- in the human spirit. Before his police work, Preib worked as a doorman at a downtown hotel, and there witnessed the grueling and often humiliating labor of those in the service industry. He soon became involved in an effort to take back the union from the corrupt old guard. Preib's been around. He knows writing -- and he knows the city's darkest corners.

These incidents speak to the bravery, the occasional dishonor, and the outright frustration of the city's police. In the wake of all this, Martin Preib's "The Wagon and Other Stories From the City" is a welcome, albeit at times maddening, effort to fashion a narrative that reflects the reality of this messy, yet vital American city. Preib has been a Chicago cop for eight years, but he's not defined by his police work. He greatly admires Walt Whitman and William Kennedy, writers who despite having seen the worst in mankind were (in the case of Kennedy, still is) capable of maintaining a faith -- admittedly quivering at times -- in the human spirit. Before his police work, Preib worked as a doorman at a downtown hotel, and there witnessed the grueling and often humiliating labor of those in the service industry. He soon became involved in an effort to take back the union from the corrupt old guard. Preib's been around. He knows writing -- and he knows the city's darkest corners.

Preib is at his best when he's telling stories. He opens with a trenchant and at times hilarious recounting of his first job in the police department, driving a wagon that transported dead bodies. His observations are keen and fresh, as when he informs us: "The dead seek the lowest places in Chicago. We find them in basements, laundry rooms, on floors next to couches, sticking out of two parked cars or shrubs next to the sidewalk." He talks of sussing out the truth in domestic disputes where in one instance a young woman uses the police to get back at a wandering boyfriend. He's called to a nursing home where an elderly woman in the early stages of dementia believes she's being held against her will. "She is listening to me explain away her independence," he writes. "Even in such a terrifying situation, she is calm and trusting of me. There is a good chance she won't ever get out of here. I am a used-car salesman." He is and he isn't. He tells her that if, after she talks with the doctor, she still feels mistreated, to give him a call.

If only Preib had stuck to telling stories, shining a flashlight into the nooks and crannies of this patchwork city. At one point, he writes that what he's learned from Whitman is that "realism does not frustrate form; it creates it. You just have to be tough enough to ride it out." I have no doubt that Preib is tough enough to ride it out, but I wish he had more faith in the power of what he shows us. Too often he wanders afield, overreaching in an effort to ponder what he's seen and heard. The prose at times feels heavy and dense. At one point, Preib launches a diatribe against the cameras that in recent years have been installed in squad cars, suggesting that they only capture the surface of what's transpired, and that as a result they pose a threat to police officers whose work is not guided by science but rather by the vicissitudes of human judgment and behavior. He seems defensive, put upon: not a good place for a writer to find him- or herself. What's more, he can't let go of his distaste for these cameras, and surprisingly -- I say surprisingly because he clearly has such an agile mind -- finds himself in a rut, a phonograph needle stuck in the groove.

Preib is a promising writer, someone whom we'll undoubtedly hear from again, someone we need to hear from again. I, for one, will read whatever he writes next. I only hope that he learns to trust his ability to spin a good yarn, and to know that a little reflection on the tails of those stories will go a long way.

Shares