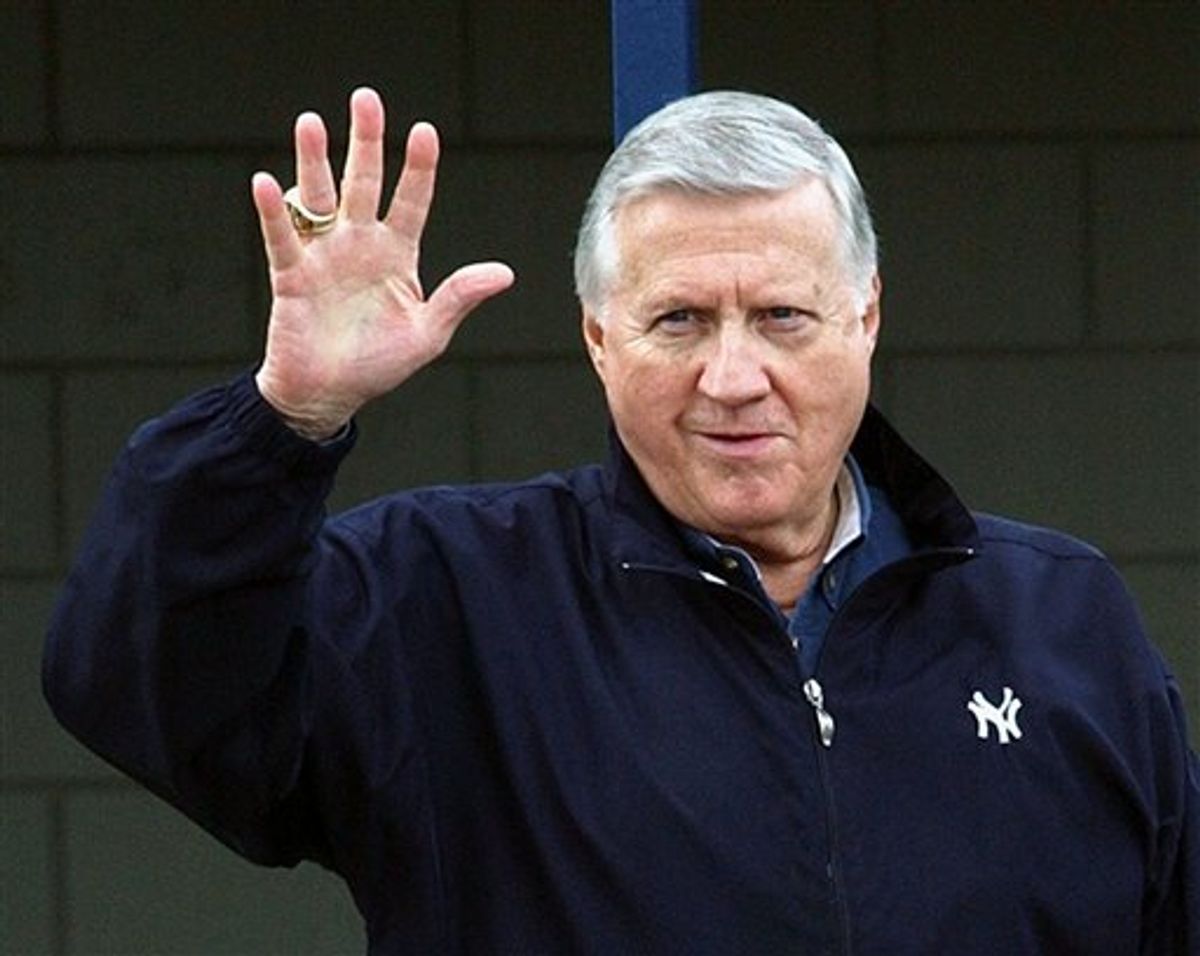

Early Tuesday morning New York Yankees owner George Steinbrenner died at the age of 80. Nicknamed "the Boss," Steinbrenner was unusual among modern team owners in going beyond his role as a financial manager and getting heavily involved in player personnel decisions. During his tenure from 1973 to 2010, the New York Yankees won 11 pennants and seven World Series titles and became perhaps the most recognizable and successful sports brand in the world.

But the boisterous and at times controversial owner had a contentious relationship with the media and many of those who worked for him. His win-at-all costs ethos helped shape not only a team and a sport but an entire city.

Salon spoke with Dave Zirin, sportswriter and author of the upcoming book "Bad Sports: How Owners Are Ruining the Games We Love," about his thoughts on the passing of an icon.

What will be George Steinbrenner's legacy?

His legacy is the first of something and last of something. He's the last of the paternalistic owners who took a great interest in seeing how a team could rebrand and reimagine a city, and who saw himself as a larger-than-life, sports version of a city's political boss. He was also the first of the owners to hold cities up for increased municipal funds, and threaten to move his team if he didn't get a sweeter stadium deal, which is a common practice now. He was also addicted to the media. In a lot of ways, many of the owners whom I would describe as destructive today learned their trade at the feet of Steinbrenner.

He's often been characterized as a public bully. Is it a bad idea for an owner to be so much in the public eye?

I think as an owner you are a steward of a team and to a larger degree a steward of the sport. Fans have the right to have a visible and accountable owner, but it's about how those owners use their place in the public eye. From Dan Snyder to Jerry Jones in the NFL, to Dan Gilbert and the Cleveland Cavaliers, you have owners who think they know more than people who've been in baseball their whole lives or know more than general managers and managers. That's also part of Steinbrenner's legacy. But being in the public eye isn't necessarily a bad thing: Mark Cuban of the Dallas Mavericks isn't very popular but is a fantastic owner. He is very visible, very bombastic, very shameless, but there's no evidence that Cuban steps on the toes of [general manager] Donnie Nelson, and tells him how to do his job. He lets the basketball people make the basketball decisions and he's willing to pour the profits he's made back into the team itself. A lot of players want to play for Dallas because of the reputation Cuban has made for Dallas. There's a degree to which Steinbrenner did that as well for the Yankees. The Yankees made him very rich and every bit of evidence shows that he took that money and plowed it back into the team with a long-term perspective that they stay the most important and profitable brand in major league baseball.

But, clearly, he also did a lot of things that were very questionable.

His greatest stain was that he started the idea of looking at the short term at the expense of the long term when it came to player personnel. A lot of obituaries will talk about how George Steinbrenner made the Yankees into a winner, but their greatest dynastic run, from 1996 to 2000, was done with homegrown talent like Derek Jeter and Andy Pettitte, and Mariano Rivera. That talent was allowed to develop because George Steinbrenner was banned from the team at the time. When Steinbrenner was reinstated to the team they had the horrible period in the 2000s where he was signing players like Kevin Brown and Randy Johnson and 30-something pitchers he thought would be quick fixes. And, as someone like me who grew up in New York, that was reminiscent of the 1980s when the Yankees had the best cumulative record for the decade in major league baseball, but failed to win one division title after 1981. They did not win one World Series in the entire decade. That's because Steinbrenner was constantly signing big-name talent and trading off incredible prospects.

How much of the Yankees success can we attribute to Steinbrenner?

He gets credit for building the Yankees into a financial juggernaut. He bought the team for $10 million, for goodness sake! And it's through that crushing financial advantage that they've been as successful as they've been. But when it comes to the actual winning of the championships I don't see how he can get credit for that given that the" Steinbrenner Way" would've meant trading minor league player Derek Jeter for a 38-year-old former Cy Young award winner.

Was his "high payroll, collect as much talent as possible" philosophy good for baseball?

It's just part of Major League Baseball's problem that it doesn't have a real way to collectivize revenue, so big-market teams have a financial advantages. You can make the case that the New York Yankees are the only team to fully exploit that advantage -- which says something positive about Steinbrenner. There are a lot of teams that make a lot of money, and don't spend it. They either stick it in their own pockets or they spend it on pressuring politicians to give them more public subsidies. Don't get me wrong, that was a part of Steinbrenner's modus operandi as well, but within the confines of the horrible financial system under which Major League Baseball operates -- regulating teams like the Pittsburgh Pirates and Kansas City Royals to oblivion before a season even starts -- George Steinbrenner did what he had to do.

Do you think he was good or bad for New York City?

On the one hand, he really was part of the energy of the city in the 1980s. The New York Post when I was growing up was Donald Trump on the front page, George Steinbrenner on the back; two egomaniacs who stood astride the city like joint colossuses of ego and excess. On that level he was one of the most defining human beings of his time. But I also think it's terribly corrosive to the city. One of the great problems of our country right now is that professional sports, particularly stadium construction, have become a substitute for anything resembling an urban policy. George Steinbrenner pushed that shifting paradigm. New York was the great testing ground for it.

Was there a difference between Steinbrenner the owner and Stein the man?

When I was 12 years old a famous sports columnist in New York City, Dick Young, passed away. He had an open service. So I thought it was a cool idea to dress up and go to the funeral, thinking there'd be a lot of fans there of this legendary writer. I showed up at the funeral and I was literally the only person who thought that was a good idea. I walked in there and everybody looked at me, like, "Who the hell are you?" And I was practically peeing my pants I was so out of place. Then I felt this meaty hand on the back of my neck and I look up and it's George Steinbrenner. And he says, "Here is the guy we've been waiting for." And he pushes me into this Park Avenue funeral home, and all I can think is: Wow, George Steinbrenner just pushed me, really hard. As soon as he did that everyone was suddenly really nice to me. Now they were asking, "Who were you again? Who are you?" as if they wanted to know me. It was this little act of mercy by George Steinbrenner on a little kid who certainly didn't deserve it.

When I researched Steinbrenner for my book "Bad Sports," which is about owners, it was interesting how that fit with other stories people had about him. It was this benevolent, Daddy Warbucks kind of figure that he tried to cut for himself. That's what I mean by saying he was a throwback and a "throw forward." He really coined and patented new ways to squeeze municipalities and exploit the media, which are so much a part of the worst aspects of sports ownership today. But on the flip side, he had a sense of himself as being a paterfamilias of the city, which I don't think is a modern title yahoos like Jerry Jones would even want.

Steinbrenner was also an expert at playing the media over the course of his career.

It was a profoundly different media environment during his time. It was a constant battle for the tabloids, the back page. Sometimes it seems like George Steinbrenner would fire a manager just to get on that back page. He fired about 23 managers in a 20-year period. It was almost pathological. And when he fired someone he did it with what can only be described as an ugly kind of flair. These were never handled quietly and never with memos, but, instead, with angry conversations over the phone, the contents of which would be leaked to his favorite sportswriters in the press. A lot of the New Yorkers in the '80s were frustrated because it seemed like he cared more about winning the back page than winning the World Series. Considering his team won more games in the '80s than any other franchise, their lack of success [in winning the World Series] was inexcusable, and it was a function of his hyper-excessive, almost manic need to sell off good young talent, fire managers and make sure he was the biggest show in town. He could not share the stage.

So what now for the Yankees?

Well, the Yankees did well when Steinbrenner was gone in the '90s and they won a championship last year after he became infirm. They had the space to sign young free agents like CC Sabathia and Mark Teixeira, and they just opened a new stadium, which, for some reason, the Major League Baseball Network today is saying he paid for largely out of his own pocket as a love note to the city. That's a total lie. The city got soaked for that stadium. Michael Bloomberg was complicit in that process, so it's unsurprising to hear Michael Bloomberg singing Steinbrenner's praises.

Looking back, what's the most positive angle we can take on George Steinbrenner?

For the city as a whole, he was authentic and never boring. The closest we have to George today is Vince McMahon or maybe Mark Cuban. Steinbrenner did what he liked to do a lot, which he said was inflicting pain and inflicting joy. The late writer Dick Schaap once said that's a very odd phrase, if you think about it: to inflict joy. For me, if not inflicting joy, he definitely inflicted a little bit of mercy, and I'll be grateful for that.

Shares