The Los Angeles Times recently marked the 50th anniversary of the 1960 Democratic National Convention by posting a few rare photos from its archive. In one, a group of young intellectuals prop up signs for the last-minute effort to draft two-time nominee Adlai Stevenson. What slogan do you pick for a candidate who has just been rejected in consecutive landslides?

"America wants him NOW."

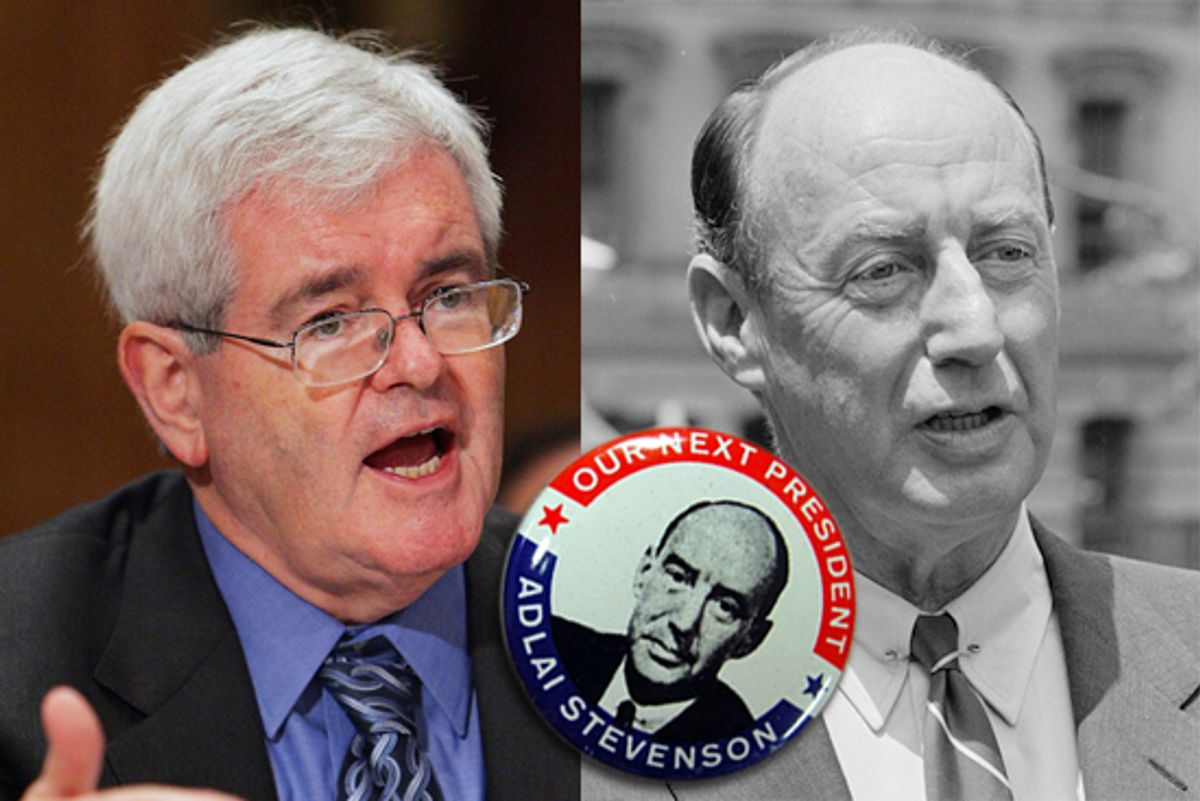

America most certainly didn't want him, but the other main contenders -- John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson -- looked flawed enough that perhaps Stevenson could get his name on the ballot, or at least get the presidential treatment one more time. The whiff of the presidency had always enticed him, just as it has with Newt Gingrich, whose flirtation with the Oval Office began anew this month when he declared in Iowa, "I've never been this serious [about a White House bid]."

But do not be fooled: "This serious" isn't that serious. Like Stevenson, Newt Gingrich isn't running for president (though he'll go along with an "if-you-must-have-me" nomination, if they're offering). What Gingrich is going for is something closer to running for ex-president.

It's a campaign to be treated like that of the elder statesman he sees every time he looks into the mirror, to retain the dignitary-behind-the-closed-door lifestyle. Whether for his personal or professional failings, Newt never secured the permanence in stature afforded to former heads of state and Washington giants, the lasting transition from middle-aged gray hair to senior citizen graybeard. And he wants it. Desperately.

So for now, an air must be cultivated. Gingrich is engaging in the travel ("ten states in the last fourteen days"), the Sunday political talk shows, and the speeches at conservative think tanks that mark the schedule of any presidential player. What gives him away is the manner in which he has raised his money.

His groups took in about $3.5 million in the second quarter -- the same amount it took Mitt Romney twice that time to raise. But while Mitt's money went into a PAC that limits how much individuals can contribute each year, Newt's went into a 527 group where all bets are off. Politico looked at the numbers and found that $935,000 of it was over the legal limit or from corporations, which PACs cannot receive money from. $100,000 came from a company engaged in deepwater oil drilling. $500,000 from a controversial casino magnate.

In exchange for the limitless donations, 527 groups are hindered in how they can spend money, prohibited from directly collaborating with campaigns the way Romney's fund can. So far, Newt's spent his coin on "a 20-plus-person staff, polling, a slick Web presence and travels across the country via private jet," according to Politico. It amounts to a personal policy center like an ex-president's -- not bad for the legacy, but no good for winning present-day allies either. And while Newt's done a little PAC business in recent months, it's still peanuts compared to that of his would-be rivals.

But who says that you have to go the modern route to the nomination? Adlai Stevenson sure didn't think so. At this time in the 1960 cycle -- the summer of '58 -- he was denouncing the primary process as too expensive and too exhausting to participate in. He then left for a long tour of the Soviet Union, receiving special dispensation to visit areas barred to Westerners, the mantle of statesman safely in tow.

It only tided him over for so long, and he allowed the Los Angeles convention to attempt to draft him, to keep him in the swim of national politics. Surely the presidency was a distant light by then. But there was also a very real, very certain outcome to his flirtation: sustenance for his dignitary lifestyle. So it is with Newt. Rack up enough 527 money in the next six months, and he can kick his heels up on those private jets for a long time.

At least, until the next presidential campaign.

Shares