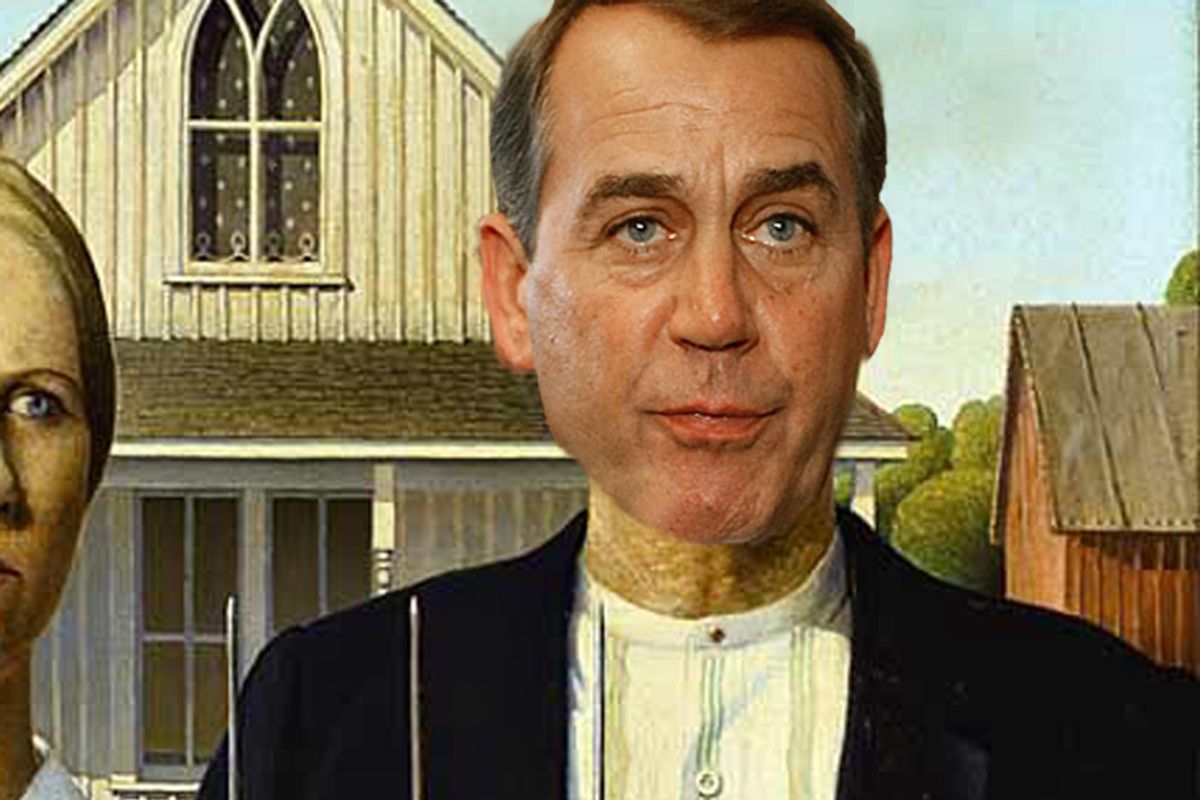

John Boehner's image makeover effort, detailed in Politico on Thursday, seems destined to fail on two fronts.

The House minority leader -- who will become the next speaker if the Republicans win back the chamber this fall -- is trying to shed his "clubby" reputation on Capitol Hill and to recast himself as a wholesome product of working-class Midwestern roots. The idea is to persuade skeptical would-be donors from far outside the Beltway that Boehner is as culturally allergic to Washington as they are -- and, presumably, to begin warming up the general public to the face of the House GOP.

If this all sounds vaguely familiar it's because Nancy Pelosi tried something similar four years ago, when Democrats found themselves with the political winds at their back -- and in position to end their 12-year exile from House control. Back then, Republicans were insisting that they'd retain control of the House by playing up the prospect of a Pelosi speakership -- Jane Fonda with a gavel, as one GOPer said to me at the time. And more than a few influential Democrats, still spooked by the savage effectiveness with which the GOP caricatured John Kerry in 2004, feared they might be right.

And so, Pelosi launched her own preemptive image campaign, one that downplayed her San Francisco liberalism and played up her Catholicism and family life. As the GOP increasingly featured her in their attacks, the stock reply from Pelosi's office would go something like this: Why are the Republicans attacking a churchgoing mother of five and grandmother of five? The Democrats' triumph that November seemed to vindicate the strategy, and when Pelosi was sworn in as speaker in January 2007, she surrounded herself with nearly a dozen children from her family -- hammering home the grandmother image.

What Pelosi and her fellow Democrats soon discovered, though, was that the inoculation campaign had been for naught. For all of the careful planning and message discipline that went into their image campaign, it didn't stop the GOP from pillorying her as a clueless San Francisco liberal (or from raising big bucks off that caricature), and it didn't buy the speaker much affection or loyalty from the general public. By the end of her first year as speaker, she sported an upside-down favorable rating -- 25 to 38 percent, which she's been stuck with ever since.

In hindsight, it's clear what happened. Before the Democrats took power after the 2006 elections, Pelosi was largely unknown to most Americans. To the extent anyone had an opinion of her back then, it was far more likely to be favorable; only hardened Republicans, who would be inclined to view anyone identified as a Democrat unfavorably, had much of a reason to express a negative view of her. So it was that Pelosi's favorable numbers outpaced her unfavorable, and that the ratio briefly spiked immediately after the '06 election, when Pelosi was showered with friendly press coverage (and before she and her party actually had to do anything).

But the minute she became speaker, everything changed and Pelosi became the face of an institution that Americans perpetually dislike. When it comes to national public opinion, it seems, the best a speaker can do is to seek anonymity -- sort of like Dennis Hastert, who hid in the shadows while his deputy, Tom DeLay, racked up awful headlines and dreadful poll numbers. But Pelosi was never interested in being another Hastert.

When it comes to Boehner, there's no reason to believe his image campaign -- should he become speaker -- will yield any more long-term success than Pelosi's has. The public just doesn't seem interested in learning about and relating to the personal side of legislative leaders. Voters are never that happy with Congress; it's just a question of how unhappy they are. And that unhappiness bleeds over into their opinions of congressional leaders.

It also seems unlikely that Boehner will convince anti-Washington conservatives -- the more immediate target of his image efforts -- that he's one of them. The fact that Boehner needs to take such pains to reach out to them in the first place is telling: The GOP's base is disenchanted with the party's Washington leadership and is reluctant to pony up money.

This disenchantment is at the heart of the Tea Party movement, which essentially represents hard-right conservatives who have traditionally voted Republican but who no longer believe that the GOP establishment means what it says. The idea that Boehner, a 20-year House veteran who stood with his party through one woefully unbalanced Bush budget after another, can appeal to these folks with a brochure that reminds them of his Ohio high school football roots is rather far-fetched.

That's the kind of pitch that might have worked in 1994, when Republican voters and donors could only dream of what their party would do if it ran the House. But not so much in 2010, when those same voters and donors remember only too well what the GOP -- and Boehner -- did do when they ran Congress.

Shares