I wrote earlier about what, to me, is silly chatter about Barack Obama replacing Joe Biden with Hillary Clinton in 2012. (And Rebecca Traister offered a different take in response.) But it occurs to me that there's a more basic question we ought to consider: Is Biden a political liability to Obama at all?

Doug Wilder, the former Virginia governor who (rather randomly) kicked off this week's round of speculation, thinks so. "Biden has not distinguished himself, other than to be more prone to gaffes -- which had been cited by some skeptics when Obama first announced his choice," he wrote on Monday. "Many had hoped a new office and new responsibilities would produce a more serious and sobered reliability in the man. Unfortunately, they have not."

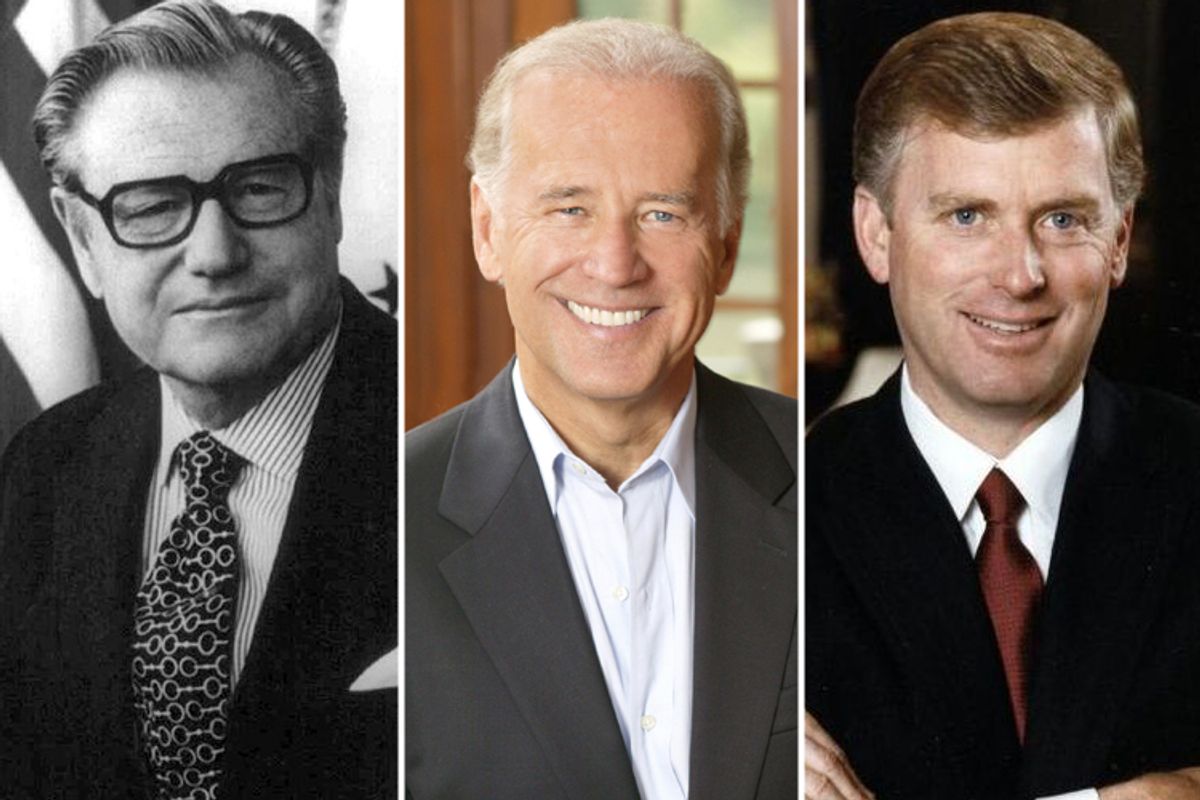

From a political standpoint, this just seems way off-base. Sure, Biden's "gaffes" are well-known, but do they really add up to anything? As Wilder noted, they were just as widely-known in the '08 campaign, but there was no evidence that they did much to erode his credibility with voters. And he performed more than ably in the only two public appearances that really matter for a V.P. nominee: his convention acceptance speech and the televised debate. I wouldn't say he's a beloved national figure, but he's hardly a Dick Cheney or Dan Quayle, either.

Which brings me to my real point: If you want to see how a vice president can really cause a president political headaches, just look at some of Biden's recent predecessors.

Two of them stirred serious dissent within the president's party. Start with Nelson Rockefeller, who was confirmed as vice president by the Senate in December 1974, the choice of accidental president Gerald Ford. Rockefeller, for whom the liberal wing of the Republican Party was nicknamed, was anathema to the GOP's ascendant conservative base, which already didn't have much use for Ford. Rockefeller's selection prompted threats of a third party movement at the 1975 CPAC conference -- although most mainstream speakers (like Jesse Helms and James Buckley) urged attendees to channel their rage into replacing Ford with Ronald Reagan in '76. It wasn't long until Ford was forced to swear off running with "Rocky" in '76 (he claimed that Rockefeller had asked off the ticket). After barely surviving Reagan's primary challenge, Ford picked the Reagan-recommended Bob Dole as his running-mate.

Then there's George H.W. Bush, the candidate of the Rockefeller wing of the GOP in the 1980 primaries. After finishing second in that race, Reagan invited him onto the ticket as a gesture of unity (and then, as president, picked Bush's confidante, Jim Baker, as his chief of staff). For the next two years, there was steady grumbling from the right that Reagan had sold his soul by teaming up with Bush, and as Reagan's 1984 reelection campaign drew closer, some conservative activists urged Reagan to replace Bush. The idea was that Reagan should pick someone who'd be a more natural heir in advance of the 1988 campaign, like Jack Kemp. But Reagan didn't bite. By mid-1983, with the economy rebounding, his grip on the GOP and its conservative base was solid; if he wanted Bush as his V.P. again, the party would allow it, and his Bush problem went away. (In the '88 primaries, Reagan stayed officially neutral and Bush survived an early threat from Dole and coasted to the nomination.)

Biden, by contrast, has no serious problems with the Democratic base.

There's also the case of Quayle, a P.R. nightmare of a V.P. if ever there was one. Bush picked Quayle, then a young, relatively unknown Indiana senator, as his No. 2 in 1988 to placate the party's right-wing. For the most part, the right loved Quayle as V.P., seeing him as a victim of the liberal media and rallying around his "family values" campaign. But his empty suit reputation, reinforced by countless bizarre blunders and misstatements, made him a national symbol of incompetence -- and prompted Baker to urge Bush to replace him on the '92 ticket. Bush refused to force the issue and Quayle never took the hint, though.

And then there's Cheney, best known now for the absurdly low poll numbers that marked his final few years in office. Fortunately for Cheney, he was considerably more popular (or less unpopular) during Bush's first term, and thus there was never any real talk about dumping him for Bush's 2004 reelection. But rest assured, there would have been had he been saddled in 2003 with the poll numbers he enjoyed in 2007 and 2008.

Again, the Quayle and Cheney examples just don't compare with Biden's. His vice presidency seems much more analogous to, say, that of Walter Mondale, Jimmy Carter's V.P. Mondale wasn't flashy and wasn't beloved, but he was a solid labor Democrat who was broadly acceptable to his party's base, who loyally served the president, and whose national poll ratings weren't remarkably high or low -- and there was never any doubt that Carter would run with him again in 1980 (even if there was doubt that Carter himself would win the presidential nomination again). When he looks at Biden, Obama probably sees -- and values -- those same attributes.

Shares