Do space flight and space exploration any longer occupy a central position in science fiction? Or has that particular Populuxe-finned rocket blasted off long ago, never again to return? Does 21st-century science fiction have anything fresh and vital to say about the realities of space travel, any inventive and plausible extrapolations that would provide rich narrative fodder for thrilling postmodern SF stories? Or is the genre doomed merely to recapitulate a well-worn fantasy of interstellar empires linked by faster-than-light schooners?

Almost since its inception, science fiction has been yoked inextricably with the notion of space voyages, particularly in the minds of the general public, who knew little of the full spectrum of SF tropes. Space flight -- that Buck Rogers/Flash Gordon stuff -- was synonymous with science fiction, and vice versa.

Almost since its inception, science fiction has been yoked inextricably with the notion of space voyages, particularly in the minds of the general public, who knew little of the full spectrum of SF tropes. Space flight -- that Buck Rogers/Flash Gordon stuff -- was synonymous with science fiction, and vice versa.

When the actual Space Age dawned in 1957, with the launch of Sputnik, the association between speculative, imaginative, technophilic literature and various real-world government astronaut programs became even more firmly cemented in public consciousness. The appearance of famous SF writers during media coverage of the first moon landing further clinched the shared identity.

But by the end of the 1960s, writers such as J.G. Ballard and Barry Malzberg began to insist on and portray a split between the genre's dreams and the oftentimes propaganda-laden and bureaucratically insipid nationalistic space programs. They argued that space travel -- at least as it was being enacted by the Soviets and the USA -- was a dead end for literature, for the soul of humanity, and for the budgetary bottom line.

With this critique bolstered by reaction to President Reagan's attempted militarization of space, SF began to retreat from realistic (and often heroic) depictions of space travel as adventure. But starting in the late 1980s, a writer like Allen Steele could once more offer solid extrapolations of our race's off-Earth future, in his "Near Space" series of novels. On the other end of the SF spectrum, cyberpunks such as Bruce Sterling and Lewis Shiner also began to limn their own radically realistic scenarios for space-going humanity.

However, the Malzberg-Ballard camp is still righteously represented today, most notably and surprisingly of late by the cutting-edge transhumanist Charles Stross, who crunched the hard numbers and the physics of space travel in a recent essay and found the likelihood of our near-term expansion into even our own solar system to hover somewhere around zero.

But recent events offer a planet-size mass of data from which science fiction might gleefully extrapolate. Private companies involved in orbital flights, filling the void left by a shrinking NASA; Indian and Chinese space programs; the completion of the International Space Station; the discovery of water on the moon and the seeming lack of life on Mars; all the alluring exotica of the Jovian moons. Science fiction seems to me duty-bound to assimilate all these yeasty tidbits and respond with some fresh stories set in the near-future of our solar system, as a continued commitment to the early dreams that launched the genre.

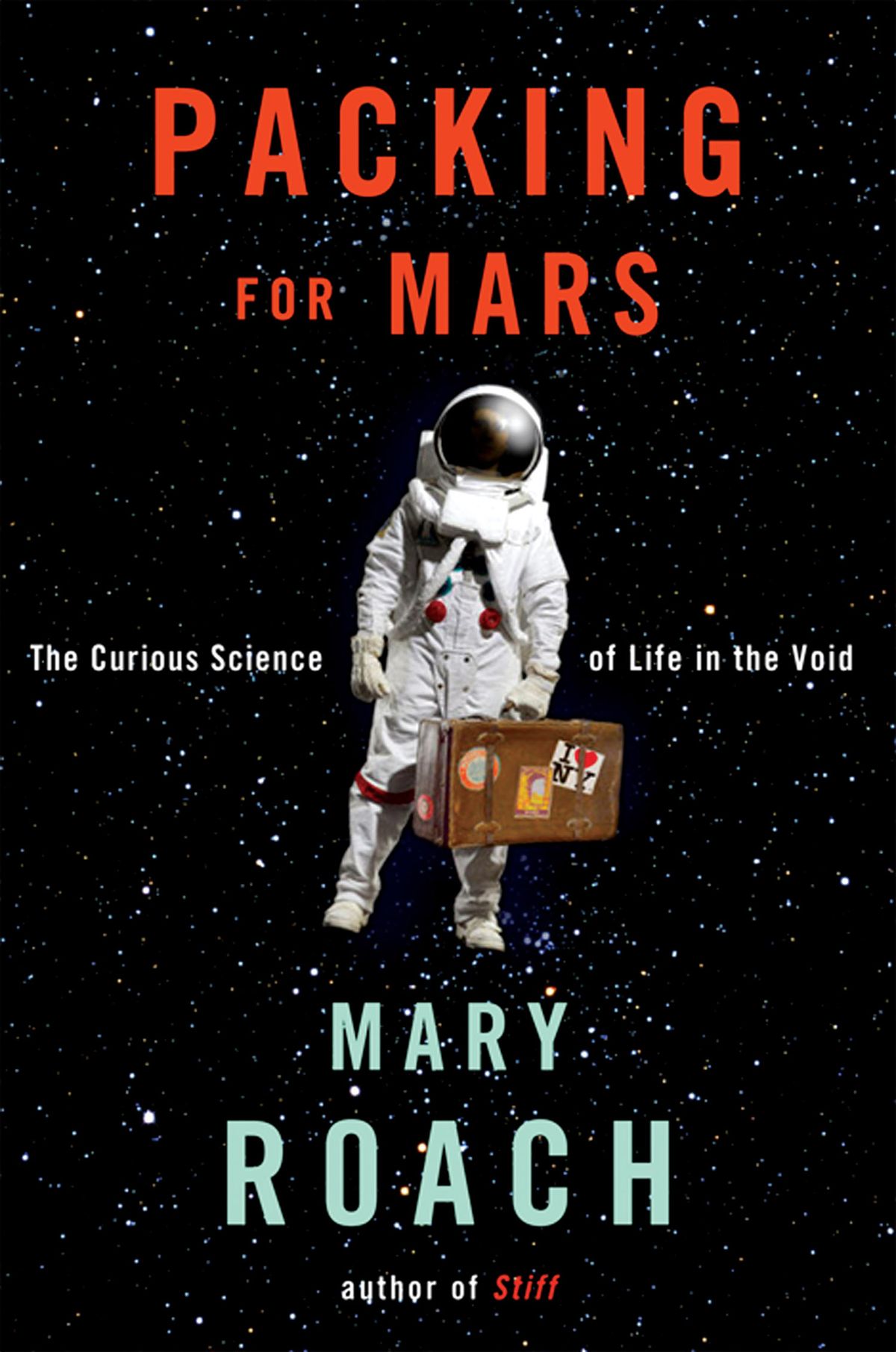

One good place to begin to get a grasp on some curious and story-rich astronautical developments is in Mary Roach's often hilarious, yet journalistically and scientifically sound new book, "Packing for Mars." As the author of three prior volumes concerning, respectively, corpses, the afterlife and sex, Roach brings a gonzo sensibility, a fluid prose style and a keen eye for absurdity to her reporting on "the curious science of life in the void." She also revels in the gritty and the macabre aspects of her topic: "[At 600 miles per hour] the windblast pried open his epiglottis and inflated his stomach like a pool toy." Her focus on the needs and engineering constraints of the human body and mind in an off-Earth environment refreshingly takes the spotlight off hardware and glorious conquest and places it squarely where Malzberg and Ballard wanted to shine it: on the ridiculous yet noble human animal at the center of space exploration.

Besides offering firsthand accounts of such little-seen contemporary procedures as the eccentric Japanese method of picking its national space voyagers and NASA's simulation of capsule crashes using corpses and a giant air gun, Roach also delves deeply into space travel's history, giving us great accounts of classic space chimps Ham and Enos; the intoxicating ecstasy that sometimes overcomes astronauts outside their ship; and how Mir cosmonauts often began to go a little batty in their extended missions. Roach reaches some sort of madcap apogee in Chapter 12 (sex in space) and Chapter 14 (bodily wastes in space). All these fascinating reports, both new and historical, are organized with an eye toward explicating and justifying the concept of a 500-day mission to Mars and all the sacrifices and novel expertise such a mission would entail. Roach's enthusiastic conclusion: "Let's squander some [money] on Mars. Let's go out and play."

Joe Haldeman must have been harking to the same tutelary deities of spaceflight as Mary Roach, or tapped into the same science zeitgeist, since his novel "Marsbound," which preceded Roach's book by two years, makes dramatically vivid, in impeccably naturalistic fashion, many of the same themes illuminated by Roach. From outer space sex and hygiene to the psychological rigors of being helpless "spam in a can" (to employ Chuck Yeager's famous derisory term for the Mercury crews), Haldeman succeeds in conveying to the reader the precise sensations and reactions of an average traveler in space, all while constructing a gripping adventure.

With a nod toward both Robert Heinlein's "Podkayne of Mars" and Kim Stanley Robinson's "Mars Trilogy," Haldeman instantly wins the reader's empathy and interest by making 18-year-old Carmen Dula his narrator -- she's as engaging and sprightly and grounded a heroine as you could want -- and by including plenty of realpolitik turmoil (2 million Israelis dead in a terrorist attack, for example).

The first half of the book, in which Carmen and family emigrate to the tiny Mars colony of only 100 brave folks, paints a very probable future for man in space, once we concede Haldeman's use of a space elevator, a mega-construction whose likelihood is not completely endorsed by many experts. But at the halfway mark of the story, when Carmen discovers a race of "Martians" (in reality, "biological machines" planted on the Red Planet specifically to monitor mankind), the book accelerates into more cosmic territory. Soon, Carmen and friends are in touch with "the Other," a Triton-dwelling representative of the creators of the Martians, who takes a decidedly unfriendly attitude toward our kind. The book ends satisfyingly, with humanity outwitting the Others, but with the race's future left in doubt.

Early this year came the sequel, "Starbound." Once again, even while opening up his story to wider galactic vistas, Haldeman scrupulously hews to realistic physics and biology and social engineering. If ever we do set out for the stars, this novel might serve as a useful primer, after taking into account the presence of as-yet hypothetical Martians and their masters.

Humanity has decided to launch a unique craft, the ad Astra, with a small crew (Carmen and friends, including some striking new characters), to the star dubbed Wolf 25, where they believe the Others live. Their objectives are part diplomacy, part espionage, part hidden aggression. Travel will be at 95 percent of light-speed, inducing the usual paradoxical relativistic effects. The round trip will occupy 13 years from the viewpoint of the voyagers, while 50 years pass back on Earth. To parallel this expanded perspective, Haldeman rotates the narrative voice from chapter to chapter among Carmen and the other crew members, a move whose utility is unquestionable, but which does dilute the charm of Carmen's voice alone.

The long interstellar trip, the meeting with the enigmatic Others, and the return to Earth after judgment by our alien superiors blends the numinosity of Arthur C. Clarke, the humbling anti-hubris of John Varley and the hard-edged and complex moral equations of Greg Bear, all climaxing in a global setback for our species. Overall, Haldeman's message resonates loud and clear: Space travel is mankind's natural destiny, the next step in our evolution -- but every evolutionary step can always end in extinction.

Haldeman had a run of mixed blessings and challenges recently, suffering from a severe bout of pancreatitis, then happily recovering and picking up the Grand Master Award from the Science Fiction Writers of America. Let us hope that, if his plans do include an extension of this saga, his energy and vision permit him to continue to chart our destiny beyond Earth's atmosphere, in the best tradition of science fiction.

Shares