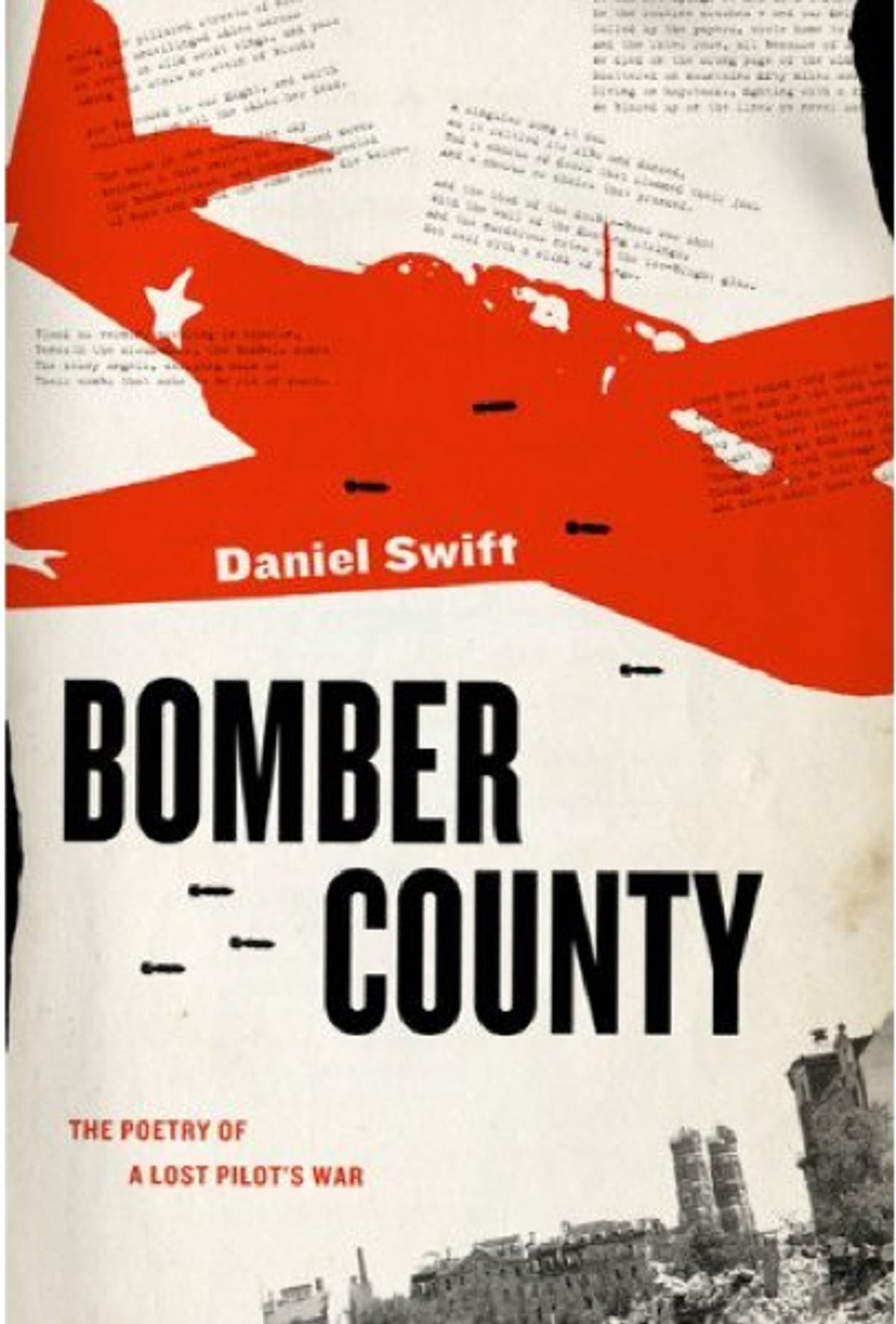

In saying of "Bomber County," this beautiful and profound book, that booksellers will be hard-pressed to know where to shelve it, I pay it a double compliment: for it is one of those rare works that defies categorization, being a tapestry of several interwoven genres at once -- a memoir, a history, an understated epic, a book about poetry and war, a personal journey, and a poignant search for a tragic truth. It ranges so widely in its references, and focuses so acutely in its vision, that it moves and impresses not only because of the sadness of the central story, but also because of the sheer scope of the meanings that the author collects around it.

A more reductive description would say that Daniel Swift has gone in search of his grandfather, a bomber pilot in the Royal Air Force who was shot down and killed in the summer of 1943 during a raid on Germany. It would also say that it is a book about war poetry, conclusively and powerfully giving the lie to the claim that the First World War monopolized this genre; for Swift shows that the Second World War's poetry-inducing equivalent of the trenches was the bombing war, in outstanding poetry both by and about the bombers and the bombed, both by and about those who fought and those who suffered.

A more reductive description would say that Daniel Swift has gone in search of his grandfather, a bomber pilot in the Royal Air Force who was shot down and killed in the summer of 1943 during a raid on Germany. It would also say that it is a book about war poetry, conclusively and powerfully giving the lie to the claim that the First World War monopolized this genre; for Swift shows that the Second World War's poetry-inducing equivalent of the trenches was the bombing war, in outstanding poetry both by and about the bombers and the bombed, both by and about those who fought and those who suffered.

I start

At sirens, sweat to feel the whole town wince

And thump, a terrified heart,

Under the bomb-strokes"

wrote Cecil Day Lewis in "Word Over All," and when one reads it in the knowledge that this is a genuine report of a horrible reality, it lances through to one's own heart, thumping to think of what has been and -- alas -- still is endured by millions in the dire territories of our human condition. Swift sees Day Lewis as challenging the bombers to write poetry from their own point of view:

"Speak for the air, your element, you hunters

Who range across the ribbed and shifting sky:

Speak for whatever gives you mastery --

Wings that bear out your purpose, quick-responsive

Finger, fighting heart, a kestrel's eye."

Day Lewis was writing from the viewpoint of the civilian craning his neck to watch the aircraft flying to their work of death, or coming to kill him and all around him: he wants their side of the experience too, and so commands them to tell us:

"Speak of the rough and tumble in the blue,

The mast-high run, the flak, the battering gales:

You that, until the life you love prevails,

Must follow death's impersonal vocation --”

Speak for the air, and tell your hunter's tales."

And, as Swift shows, quite a few did so, in poetry sometimes of the highest quality. When the response came, it could have a shattering frankness:

"In bombers named for girls, we burned

The cities we had learned about in school --“

Till our lives wore out."

Thus Randall Jarrell, airman.

"Where cloud rained fire, and we were in the cloud --”

Its climate, dark, and deluge. And we spread

Simple as rain, like thunder loud,

To be the following weather of the dead."

Thus John Ciardi, rear-gunner in a B-29 bombing Japan.

The point is not that Swift's grandfather was a poet, for he was not. It is instead that in seeking to understand the warrior life and warrior death of his lost grandfather, who was killed in action when Swift's own father was a very small boy, Swift discovered that it was not just the detailed archives kept by both sides in the struggle, not just the survivors, reminiscences, debates and histories, that fill out the picture of Squadron Leader J. E. Swift's military life and death, but poetry: remarkable poetry, all the more remarkable when one sees it in the context Swift provides. Poetry is a torch that shines into experience, and in this book its light is so brilliant that it illuminates not only the landscape of that era, but individual figures within it, including that of the lost Squadron Leader.

I should declare an interest. Swift mentions my own book on the bombing campaigns of the Second World War, in which I essay a moral audit of one significant aspect of it, namely "area bombing," which is the indiscriminate aerial bombardment of civilian populations with the aim of terrorizing them, killing large numbers of them outright, and destroying the survivors' means of existence. He does not agree with all my conclusions, which are that although the primary duty of the Allied powers was to vanquish Nazism and Japanese aggression, the use of area bombing as one means to that end was not morally justified; and further, that it lacked the uncomfortable justification of being essential to achieving victory, which it was not -- for in fact it might even have prolonged the war, and made it harder for the Allies to win.

So I lavish praise on Swift's remarkable book not because we are on the same side of the argument, for we are not wholly so. It is because, having read many books about the air war, and having written about it myself, I recognize the special qualities of Swift's account: scrupulous research, perceptiveness, sensitivity, depth of personal engagement, synoptic understanding and breadth of intellectual sympathy, all going far beyond the usual histories and memoirs on the subject.

One thing we emphatically agree about, though, is the heroism of the flyers. Fifty-five thousand British and Commonwealth airmen died in the dangerous skies over Europe during the war; 45,000 USAAF airmen died there and over the Pacific likewise. These were great sacrifices, and they were made in circumstances that would test the courage of the best in any war. For them and the survivors who flew in fighters and bombers alike I have the greatest admiration. Though one aspect of the bombing war was a major moral error, that fact does not impugn the courage of the air crews or the scars, visible and otherwise, of the veterans alive today. They have an epic stature, not least those among them whose retrospective on their war chimes with the kind of memory James Dickey captures, opening a fridge door late at night decades after bombing Japan:

"a reed mat catches fire

From me, it explodes through field after field

Bearing its sleeper another

Bomb finds a home

And clings to it like a child."

Swift builds a picture of his grandfather's experience from a wide range of apt resources, from Hector's farewell to Andromache before his fatal contest with Achilles in the "Iliad," through Dante's inferno, to Breughel's painting of Icarus plunging from the sky -- just as his grandfather had plunged from the sky into the North Sea, still in the cockpit of his Lancaster bomber. He was on his way back from a raid on Münster, and Swift's careful research suggests that he was probably shot down by a Luftwaffe night-fighter pilot called Oberfeldwebel Karl-Heinz Scherfling, flying a Messerschmitt 110. Scherfling was in his early twenties at the time, and was himself killed in action the following year: the tragedy of lives lost, individually and in the mass, was not reserved to just one side of the argument.

Swift went to speak to Germans who had endured the onslaught of the Allies, so vastly greater than the Blitz on Britain in 1940 and the indiscriminate missile attacks by V1 and V2 rockets on London and elsewhere in the summer of 1944. These attacks, as polling showed, made their victims less likely to wish for retaliatory bombing on Germany than those who had not been bombed; the people keenest on bombing Germany to smithereens were Americans in their unbombed cities far across the Atlantic.

And when Swift sat in the kitchens of old ladies in Cologne and elsewhere, hearing them speak of their experiences, one of the things he remembered about the encounters was laughter; they had all shared in the double-sided tragedy that was bombing, and were released from the obligations of apology.

At the end of the war Churchill's personal physician, Lord Moran, wrote a book called "The Anatomy of Courage" about how military personnel withstand the stresses of combat. He remarked, "We must practise a prudent economy of emotion in time of war if we are to remain sane." Swift discusses the need for such economy, particularly by limiting the imagination. Imagination made the work called for in war impossible; waiting for tonight's raid and picturing one's aircraft falling like a burning torch from the sky would unnerve one too much. He sees in what is never mentioned or even alluded to in his grandfather's letters evidence of a tight mastery of imagination. "There is no news," his letters to his family often say, shortly after and before going on bombing raids. Quoting Dante's "I, one man alone / prepared myself to face the double war / of the journey and the pity," Swift comments that "To be a bomber is daily to war against an alternative version of your own story."

Swift tells us that a naturalist who studied postwar bomb sites in London found them rich in unexpected wildlife. Rosebay willow-herb had sprung up on scorched-earth sites cleared of rubble; black redstarts that normally nest in rocky cliff-crags had colonised the broken walls and exposed interiors of bombed-out buildings. The strange beauty of cities on fire -- stark silhouettes against flames, water-covered streets where the fire-fighters struggled, reflecting the roaring inferno around them -- had transmogrified into subtle reclamations by other kinds of beauty.

When the bombing stopped in those landscapes the dead were silent, the survivors weary; the droning aircraft high above had gone home. Decades later Swift and his father traveled to the Netherlands to visit the cemetery where Squadron Leader J. E. Swift was buried, and to visit the beach where his body had washed up. They spoke to Dutch people who are still finding remains of crashed warplanes -- eight feet underground in some cases, so violent were the impacts. Sometimes the Dutch find unexploded bombs, too.

Swift was taken by one of the officials to see a recent war find.

For lunch, we have fried eggs with ham, and Gouda cheese in plastic wraps. We drink milk and eat an apple after, and then he takes me to a warehouse and shows me three wooden boxes full of jagged silver pieces. They are as sharp as a knife, he says, but to me they look like great boxes of salad. There are valves, pistons, the throttle. There are two engines and three propellers of a Lancaster ED 603, found fifteen metres down in the Ijsselmeer. One engine weighs 4000 lbs, and the propellers are twisted and organic. The whole looks once alive, with the barnacles and the propellers like fins and the valves below like gills.

This understated but piercing prose, this clarity, this juxtaposition of fried eggs with the twisted propellers of a four-engined bomber that was the coffin of dooming and then doomed men, is writing of an exceptional order. Combine it with its intricately woven personal and universal subject matters, and a classic emerges. Of all the books about war that I have read -- all war, not just the bombing war--this is among the most moving and telling.

Shares