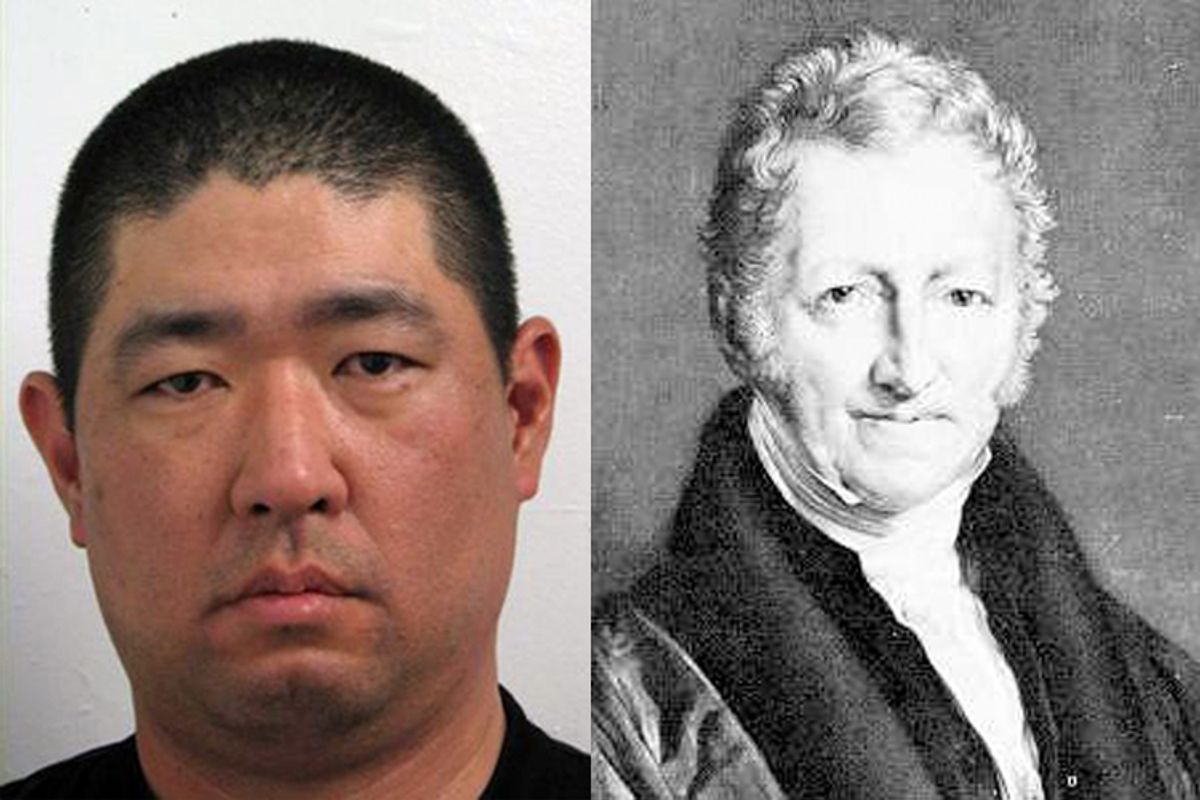

Among the demands of James Lee, the deranged gunman who rampaged through the headquarters of the Discovery Channel in Washington, D.C., before being shot and killed late Wednesday afternoon, was a request that the TV network "develop shows that mention the Malthusian sciences about how food production leads to the overpopulation of the Human race."

Insane, but perhaps not quite as kooky as it might initially seem. Because when choosing crazy-making prophets of doom and destruction as your inspiration, you could do a lot worse than the late 18th-century economist Rev. Thomas Robert Malthus.

The original "dismal scientist's" main contribution to economics -- the theory that the growth of population would always outrun the growth of production, thus dooming humanity to crushing poverty -- was proven wrong by the Industrial Revolution almost immediately after he set his thoughts down on paper. Few theorists whose names have endured for centuries have been more spectacularly off the mark. In almost every measurable way, the world is immensely richer than it was at the time of Malthus, even in the face of a surge in global population that the economist would never have dreamed remotely feasible. For at least the last century Malthus' ideas have been routinely dismissed in introductory economics textbooks and scoffed at by most mainstream economists, whether liberal or conservative, Keynesian or Chicago School.

Not only has food production outpaced population growth, thanks to technological innovation, but the richest nations on the planet tend to be the ones in which the birth rate drops the fastest -- the so-called demographic transition. So Malthus was wrong twice.

And yet his dystopian vision that humanity's lot, our inescapable fate, will be grinding, desperate poverty, lives on. Down for more than 200 years, but not yet out, because there's always a get-out-of-jail-free card for Malthus: Just wait.

Just wait until the technological wellsprings of innovation run dry, when even the most advanced genetic modification technologies can no longer boost food yields. Just wait until peak oil puts an end to the age of cheap energy, until the oceans are overfished and the atmosphere is choked with carbon dioxide. Just wait until Chinese and Indians and Brazilians consume with the same unsustainable abandon as Americans. Malthus isn't wrong -- he just isn't right ... yet.

Malthus stays popular, he disturbs our dreams and sends mentally disabled people rushing to the local gun store, because that unsettling question -- is the Industrial Revolution sustainable? -- lurks in the dark recesses of our collective consciousness. We've had a pretty good ride, especially in the West, for the last couple of hundred years, but where is it written in stone that our great fortune is a permanent state of affairs? Who gets the last laugh? All those economists, serene in their assumption that human ingenuity will keep on innovating our way out of the bottleneck? Or Malthus?

With this background, the connection between environmentalist concerns and the work of Thomas Malthus is easy to make, especially when one is considering the subset of environmentalists who believe that unchecked population growth is the planet's biggest problem. So no question, poor James Lee is already becoming the latest front in the culture wars. Any suggestion of resource limits spawns ideological division. The free market, in this formulation, is either Malthus' worst enemy, or will ultimately prove him right. Capitalist self-interest will either keep finding new resources to exploit, or ways to exploit them more cheaply, or will empty its bag of tricks and, suddenly, we're headed back to the Dark Ages. Pick your side.

But what made crazy James Lee's craziness bizarrely more interesting than your run-of-the-mill whacko eruption was his very first demand:

"The Discovery Channel and it's affiliate channels MUST have daily television programs at prime time slots based on Daniel Quinn's 'My Ishmael' pages 207-212 where solutions to save the planet would be done in the same way as the Industrial Revolution was done, by people building on each other's inventive ideas."

"My Ishmael" is a very odd book. I haven't read it from start to finish, but I've skimmed it, and paid close attention to the section called out above. Best I can tell, it features the philosophic, economic and sociological observations of a telepathic, intelligent gorilla as told to a young girl. Fox News anchors are already reading passages of it aloud to their readers, and everybody's getting a good chortle.

I can't tell you whether it is true, as some tweets are declaring, that "My Ishmael" is "anti-religion anti-human anti-capitalism pro-gang pro-commie racist BS." But I can tell you that the section where the gorilla discusses the Industrial Revolution bears a pretty astounding similarity to the new growth economic theory of Paul Romer. This gorilla kind of knows what he's talking (or thinking loudly) about. Paul Romer is no wacko. He makes a compelling, mathematically grounded case that the key to economic growth is the widespread production and distribution of information. That's how the Industrial Revolution took off, that's how scientific knowledge accelerates -- that's the pathway to the utopian Star Trek future.

Saith the gorilla:

James Watt is often credited with inventing the steam engine that started it all, but this is a misleading simplification that misses the whole point of this revolution. James Watt in 1763 merely improved on an engine designed in 1712 by Thomas Newcomen, who had merely improved on an engine designed in 1702 by Thomas Savery, who doubtless knew the engine described in 1663 by Edward Somerset, which was only a variation of Salomon de Caus's 1615 steam fountain, which was in fact very like a device described thirteen years earlier by Giambattista della Porta, who was the first to make any significant use of steam power since the time of Hero of Alexander in the first century of the Christian era. This is an excellent demonstration of how the Industrial Revolution worked.

In other words, we progress by copying, tinkering and making gradual improvements. One of new growth theory's primary insights is that if you put up impediments to the spread of knowledge -- like overly strong patent and copyright laws -- you create friction that slows down economic growth. This does not mean abolishing all intellectual property laws; it means finding the right balance between property rights and the freedom to share and innovate so as to create a more prosperous, equitable society for all.

Talking (or telepathic) gorillas, Malthus-gone-wild, a deranged armed man wreaking havoc on the Discovery Channel: It's a crazy stew, and it will only get crazier as political opportunists start weighing in. Lee's own manifesto doesn't hold together in the slightest. If you believe, as he purports to do, in finding ways to unleash the creativity that spawned the original Industrial Revolution, then you don't have to worry at all about population growth or immigration or the "pollution" of "filthy human children." Those children -- those newly educated Chinese and Indians and Brazilians -- are exactly the people who will come up with the ideas and innovations that keep us hurtling forward into the unknown future.

Unless, of course, they are prevented from doing so by governments in thrall to special interests, corporations intent on monopoly control, politically motivated attacks on the scientific method, and a growing chorus of ranters who wear ignorance as their coat of arms and shout down all those with whom they disagree. We probably have the tools to solve the big problems that face us this century, but our own stupidity may well prevent us from properly using them. That's truly crazy making and we'd better get used to the collateral damage.

Shares