I don't like William Gibson's Op-Ed piece on Google in today's New York Times merely because, barely a week after I went all Jeremy Bentham Panopticonic on the cat bin lady, he writes that "Jeremy Bentham's Panopticon prison design is a perennial metaphor in discussions of digital surveillance and data mining, but it doesn't really suit an entity like Google." Even though it's kind of a put-down (perennial!), still, great minds think almost alike, right?

Nor am I content just to revel in the crispness of his prose:

Google is a distributed entity, a two-way membrane, a game-changing tool on the order of the equally handy flint hand ax, with which we chop our way through the very densest thickets of information.

That's some nice work. It doesn't matter what the format is, tweet, Op-Ed column or novel; the man knows what he is about with the English language. (Seriously, Gibson tweets like a cyborg-Mozart. He's unstoppable!)

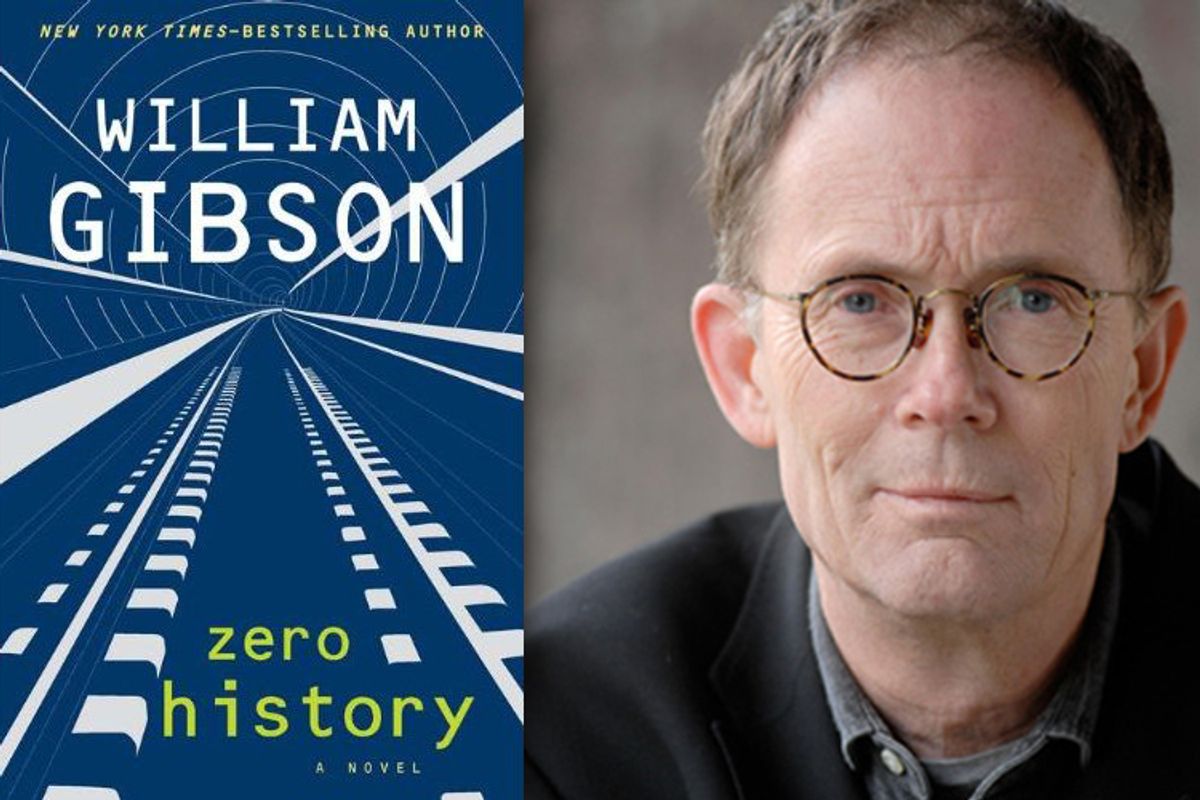

But we knew that already. No, what I like most about Gibson's column is how he manages to plumb, in his consideration of Google, depths that are equal parts menacing and cool, just as he does in his novels, including his newest offering, "Zero History," arriving momentarily at a bookstore or e-reader near you.

The cyberspace of "Neuromancer," Gibson's first novel, established the template. When Case jacked into his Ono-Sendai deck and merged his consciousness with the data flow, the adventure seemed simultaneously hip and dangerous, cool and spooky.

So is Google -- that handy flint ax and instrument of collaborative surveillance. Google knows too much about us, while helping us find out whatever it is we want to know. The two functions, of course, are complementary. You don't get the enlightenment without giving up some privacy. Few writers are better situated to explore this cyber-generated paradox than Gibson.

In his newest novel, Gibson continues his career-long flight from cyberspace into something more or less analogous to the present day. Malign Japanese transnational corporations have been replaced by the military-industrial-fashion complex. (Cool, yet scary, just like Google.) Denim jeans push the plot harder than silicon wizardry. But the sensibility is the same, even if cyberspace jockies have been replaced by ex-punk rock singers with a nose for street-level haute couture. It's a good read.

But even as abreast of the zeitgeist, or ahead of it, as Gibson usually operates, Google is moving more quickly than even a well-timed Op-Ed column in the New York Times can manage. Just yesterday, my Twitter feed was alive with discussion of a new feature for Google's Gmail, Priority Inbox. Currently in elite beta testing, Priority Inbox is supposed to be able to float the really "important" e-mails to the top of your queue, while dropping down the mailing list flame wars, office gossip and other extraneous bullshit that clogs up our e-mail pipes every day.

Of course, to do this, Gmail has to figure out even more about us than it already knows. Who are the correspondents we judge more deserving of our attention, et cetera? The trade-off is obvious. The give and take between utility and panopticonic omniscience is as exquisitely illustrated by Priority Inbox as anything Gibson name-checks.

And I want it, even as I bristle at the idea that Google can figure out what my priorities are without my help. Given the track record of the past decade, I'm trusting Google to deliver on its promises. Just as I trust Gibson to keep writing excellent novels.

Only difference, with Gibson, there's no downside.

Shares