Early in "The Romantics," writer-director Galt Niederhoffer's film about a group of 30-something college friends reuniting for a wedding, there's a scene where the bride-to-be, Lila (Anna Paquin), goes up to her room following the rehearsal dinner, sits on her bed, and takes off her high-heeled shoes. The camera stays on her as she sits there collecting her thoughts, listening to the sounds of the house, and to her friends talking on the lawn below, preparing for a night of drunken tomfoolery. After a moment Lila stands up, walks to the window and looks down at her friends as if debating whether to join them. There's no score, just natural sound. There are no cuts, either. Niederhoffer isn't afraid of inaction, of visual and aural quiet that verges on dead space; the entire scene lasts somewhere between a minute and 90 seconds, during which she's not hurriedly advancing the plot. She's luxuriating in a moment.

By current commercial filmmaking standards, it's not a good scene. It's too pokey, there's too much silence on the soundtrack, and there's nothing on-screen that straightforwardly suggests where the plot might be headed next, or what Lila (whose fiancé once dated a member of the wedding party) is thinking and feeling. Yet I loved this scene and others like it in "The Romantics," and afterward I found myself thinking fondly of the movie and asking myself what it was about it that made me want to revisit it. It's just another wedding movie, really -- part of a highly ritualized subgenre of romantic comedy that's been done to death and that should probably be retired for a while until something truly new can be added. But I wasn't thinking about any of this while I was watching it. I was wrapped up in the characters, the story and the sense of place, and thinking that if I had to choose one word to describe what the filmmaker was doing, I'd probably go with "adult."

What do we mean when we call a film or TV show "adult"?

The word is often used to refer to language, violence, sexual imagery or other material that adults don't want small children to see. But other films are "adult" in a different, arguably truer sense. They tell stories about people and situations that children (and the childishly minded) either cannot understand or aren't interested in. And they tell them in ways that demand engagement from the viewer, rather than slack-jawed spectatorship. These aren't "shows." They're situations involving somewhat believable adults involved in emotional and sometimes moral conundrums. And you don't always know whom to root for, or if you should root for anyone. Without revealing any major plot twists, suffice to say that the college friends in "The Romantics" have, to quote another character, "an incestuous dating history," and that by the end of the weekend they've relapsed into old behavior, and said and done things they'll regret later.

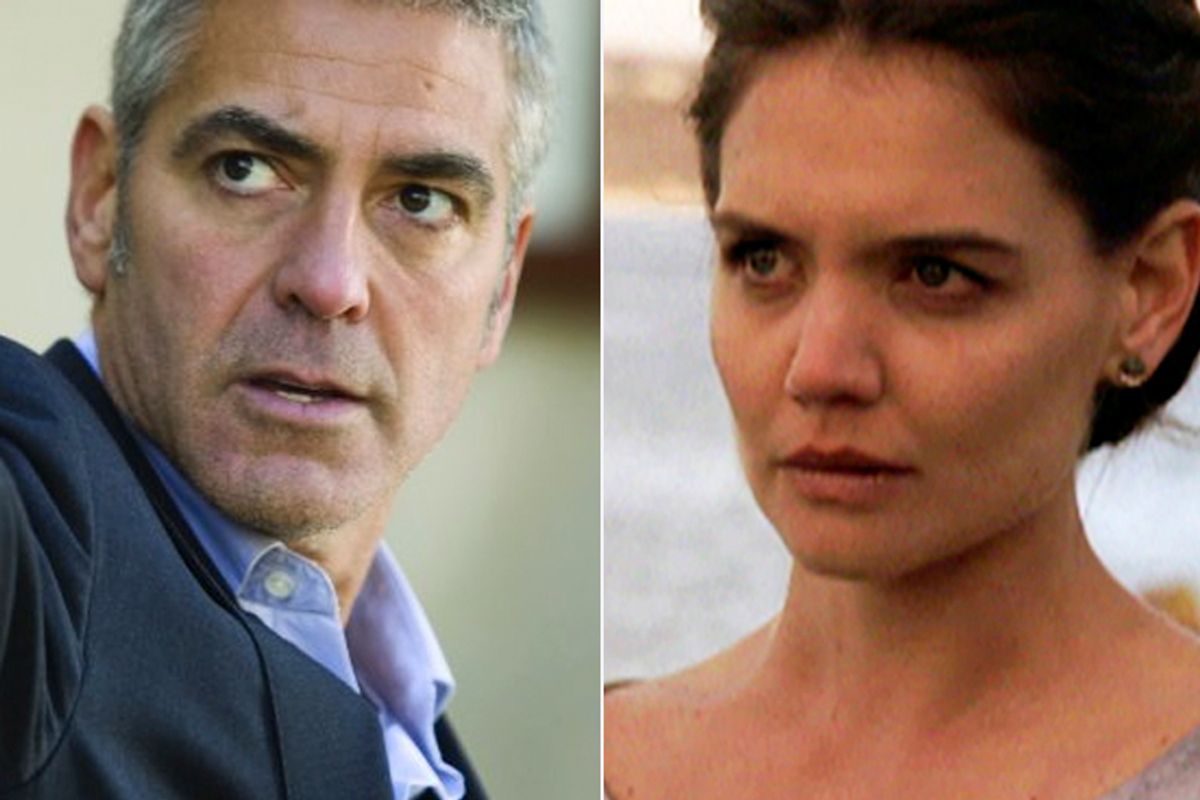

The plot finds straitlaced drudge Lila fearing that her groom, the brooding and bookish Tom (Josh Duhamel), is still in love with Lila's best friend, a novelist named Laura (Katie Holmes), and the whole wedding party getting thrown into a tizzy when Tom disappears without warning. You've seen variations of this story before. And the characters are somewhat emotionally arrested, talking and behaving as if they're still in their early 20s (to be fair, though, this is a hothouse situation -- back in the world, they probably act differently).

But as critic Jim Emerson is fond of saying, a film isn't about what it's about -- it's about how it's about it. Between the comparatively laid-back directorial style, which lets the situations breathe and the actors act, "The Romantics" has a more grown-up feel than you'd ordinarily expect from a wedding comedy. There aren't too many feature-length theatrical films being made this way in the United States, cast with recognizable names and given a wide release. And when such a film does appear, it's apt to have a tough time in the marketplace. I can think of a couple of other 2010 examples of what I'd call adult mainstream films -- movies that let you spend time with morally compromised characters and that sort of hang back a bit directorially, letting the scenes and situations breathe, and mostly resisting the urge to tell you what the movie thinks of anyone, preferring instead to simply present the characters and let you feel however you want to feel. Given what American film has mostly become (loud, trashy, stupid and devoid of even the most rudimentary interest in complex storytelling or characterization) it's a miracle such films even get made, much less released.

The spring 2010 Michael Douglas vehicle "Solitary Man," about the twilight of a womanizing alpha male, takes this sort of approach, rooting itself in Douglas' aging bad boy charisma and letting you be amused and repulsed by the character's actions, sometimes within the same scene. At no point does the film suggest that the hero deserves a pass for being funny and edgy. The script remains fully aware of the damage he has inflicted over time. But our reactions (like the reactions of his friends and family members) remain conflicted. The final shot leaves both the story and the hero's development suspended. He could redeem himself or he could revert -- you just don't know. Here, as in "The Romantics," it's the attitude of the filmmakers that defines the movie as adult. The description of the plot makes it sound like what it is: yet another Michael Douglas movie about a charismatic heel, minus the high-concept elements that made Douglas a superstar in the '80s and '90s. It's the execution -- and the filmmakers' choice of what to emphasize, namely little moments -- that makes it notable. There are a lot of scenes where the movie just watches the hero as he watches other people, contemplating a sexual or moneymaking gambit or musing on once-healthy relationships he's destroyed with intense regret and sadness. It's a movie about the past catching up to you. As of this writing, "Solitary Man" has made less than $5 million theatrically. "Iron Man 2" made that much in its first morning of release.

Another current movie, "The American," can also be called "adult," and not just because it shows its title character, an assassin named Jack (George Clooney), graphically killing a couple of people and having sex with a beautiful prostitute who can barely get through a whole scene without taking her clothes off. Like "The Romantics" and "Solitary Man," "The American" is adult not by virtue of what it shows but because of how it tells its story and what it chooses to focus on. The nudity and violence earned the film an "R" rating, but they're minuscule aspects of the movie, which is composed largely of scenes where Clooney's character, Jack, plies his trade or contemplates his life in silence or near-silence. By American blockbuster standards, it's a slow film, so slow that many critics tagged it the ultimate mainstream audience-repelling adjective: European. This isn't a movie about one of those chatterbox charmers with silenced pistols who cavorts through explosive set pieces, trading pop culture references as if "Pulp Fiction" just came out last week. It's a film about a man who has done terrible things that weigh on him, and who on some level fears that his soul is in peril (even though, when a priest presses him on the issue, he shrugs it off).

"The American" made a healthy $16.4 million last weekend, but I suspect this is mainly due to Clooney's name. The releasing studio, Focus Features, very nearly dumped the film, releasing it in the middle of the week prior to Labor Day weekend and giving it very little publicity (aside from some stark posters and billboards in major cities that made it look action-packed). I saw the film in a theater this weekend, and during the final scene -- which I found quite powerful, if admittedly melodramatic and intensely sad -- a man behind me sighed disgustedly, "This is terrible!" And on the way out I heard a woman tell her companion, "Please don't tell anybody I paid to see this."

I won't return yet again to the old canard that American cinema was once lousy with thoughtful little mainstream films that were more about character and atmosphere than spectacle, because such laments always involve a lot of nostalgic exaggeration. Most movies are, and always have been, garbage that treats dialogue as the thing we all have to suffer through en route to the next explosion, death or gadget. But there was once more marketplace room afforded to films like the ones mentioned above. They were part of the national moviegoing conversation not because they were out-of-the-mainstream oddities but because they were accessible films with serious intentions, examining the consequences of actions, the fungibility of moral codes, the weight of the past and other subjects that children and the simple-minded would find boring. If you want to see these kinds of stories today, you have to rent old movies on DVD, or subscribe to cable.

Shares