(Corrected below)

When PBS released Ken Burns’ “Baseball” in September 1994, it was an oasis in a punishing desert for the game’s fans, since a brutal strike had stopped the 1994 season in August, unbelievably. For those of us who cared, the sudden halt of the summer game was like the sun failing to come up in the morning. Burns’ 18 hours of “Baseball” on PBS wasn’t as rewarding as a September pennant race, but it was pretty great, maybe even better than watching your team play meaningless late-season ball. For me (and I think Burns as well) the heart of the story was Jackie Robinson heroically integrating the game with the Brooklyn Dodgers, the story of New York baseball in the 1950s — the world of my baseball-crazy parents and grandparents, the stories I’d grown up on though I wasn’t born yet — and the lost tales of the Negro Leagues, some of them told by the star of the series, Kansas City Monarchs manager Buck O’Neil, who has since died.

“Tenth Inning” picks up baseball after the devastating strike that silenced the game back when Burns’ opus debuted, as though the filmmaker realized he’d missed a crucial part of the story by wrapping too soon. I wrote about “Baseball” in 1994, and I got to spend a day with Burns talking about it. As much as I loved it, I had a few quibbles: Too many white male intellectuals talking about a game with a working-class heart, plus the only women were Robinson’s wife, Rachel (who was one of the series’s stars, to be fair), and Doris Kearns Goodwin. I loved both, but two women in 18-plus hours of documentary seemed off.

“Tenth Inning” corrects some of those distracting flaws. We still get George Will, Daniel Okrent and John Thorn, but Burns adds two wonderful primary voices, ESPN’s Howard Bryant and the Sacramento Bee’s Marcus Breton. With his groundbreaking and scrupulously fair writing about steroids, Bryant becomes the vivid, trustworthy conscience of the project, while Breton, telling the story of the game’s rising Latino base (as well as my San Francisco Giants), contributes much of its heart. Burns also manages to recruit one of “Baseball’s” most prominent critics from 1994, MSNBC star (and former ESPN host) Keith Olbermann. Where Olbermann trashed Burns’ earlier work for (by his count) 160 errors, now he opens “Tenth Inning” with a meditation on baseball’s greatness because “you’re watching the same game that somebody watched in 1860″…”the only sport that goes forwards and backwards.”

At four-plus hours detailing 15 years, “Tenth Inning” lacks the sweep of Burns’ earlier work, but there’s a lot to enjoy. He shines telling the stories of former Yankees manager Joe Torre, the son of an abusive father who stood up to Yankees owner George Steinbrenner when Steinbrenner trashed Yankee players, and created a dynasty that straddled the old and new century; the great Latin wave of talent, personified by a beguiling Pedro Martinez, and the singular Japanese star Ichiro Suzuki, who talks to Burns through a translator yet speaks to us directly with his eyes and his on-field magic. The wiry, fleet-footed Ichiro becomes a counterpoint to the home-run stars of the era – a time we now know was dominated by the steroid scandal, which in many ways provides the sobering narrative arc of Burns’ new story.

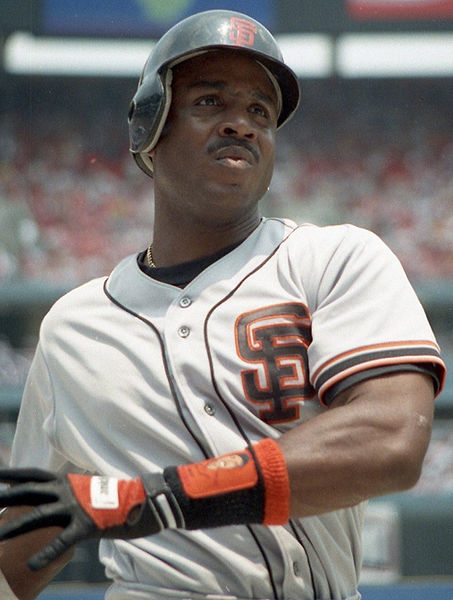

I have heard people I respect say that “Tenth Inning” makes Barry Bonds a sympathetic figure, and I can see that point of view, but I don’t share it. The story starts with Bonds’ angry father, Bobby, a star with the Giants, mentored by Willie Mays (who became Barry’s godfather), who somehow never fulfilled his promise. Burns shows the racism Bonds faced as a black baseball pioneer even in the 1960s, and how his suspicion and resentment, as well as that of Mays, fostered Barry’s often hostile relationships, not only with the media but with the game itself.

But Burns belies his human sympathy for Bonds with a filmmaker’s ham-handed symbolism: It’s always a little darker when Barry Bonds is in the picture. When he and his father are introduced minutes into the first segment, the music gets ominous, a little bit like the twangy soundtrack to an old western, as you wait for the bad guy to walk in the barroom doors. Even as Burns explains that Bonds turned to steroids after 1998, when he watched the juiced escapades of Sammy Sosa and Mark McGwire overshadow a season in which he became the first player to hit 400 home runs and steal 400 bases in a career, Part 1 ends with a menacing Bonds looking like he’s getting ready to destroy the game in a whole new way in Part 2.

In almost every shot, Bonds is glowering (except during the 2001 McGwire record chase, where the occasionally grinning Bonds looks manic, and the objectively gorgeous AT&T Park looks overexposed, bright and garish). In Part 2 George Will recounts Bonds’ already storied life in baseball, before he showed up in 1999 with a reported extra 20 pounds of muscle: “He already had a Hall of Fame career, but that wasn’t good enough.” Unfortunately, that it wasn’t good enough seems for Burns to be about Bonds’ moral and psychological failings, rather than the way McGwire and Sosa had already changed the game.

Also from early in Part 1, Bonds’ San Francisco Giants seem to be the hard luck team whose owners and fans might do anything — even cheat — to win a World Series. Giants fans are described as “forlorn … desperate for redemption.” Even the sympathetic Marcus Breton suggests “It has to be a character flaw to care so much” about his benighted team, as he talks about “the many bargains Giants fans have made with themselves over the fact that there’s no title … Barry was the next best thing.” Bonds’ transgressions even seem, in Burns’ telling, to be a reason for his team’s 2002 World Series collapse. Up three games to two against the Angels in Anaheim, leading 5-0 in Game 6, the Giants fell apart as champagne chilled in their clubhouse — one of the worst memories (apart from someone I love dying) of my entire life, in the interest of full disclosure. Bonds had a postseason for the ages in 2002, despite a reputation for choking in October, but the Angels’ Troy Glaus was the Series MVP (and Glaus, of course, would later be exposed as another steroids user).

Of course, the Giants’ counterpoint in “Tenth Inning” is the Boston Red Sox, whose fairy-tale rise becomes the sunny center of an otherwise fairly dark tale of baseball’s last 15 years. In fact, “Tenth Inning” shifts directly from the Giants’ World Series loss, featuring Bonds’ despair and manager Dusty Baker’s 3-year-old son Darren sobbing, to smiling Red Sox fan Mike Barnicle introducing his team’s admittedly historic and wonderful win. As a fan, I can’t begrudge a powerful filmmaker using his talents to highlight the team he loves (even as he diminishes mine, and also slights the World Series wins of the Philadelphia Phillies, Arizona Diamondbacks and Chicago White Sox, plus the last-to-first turnaround of the Tampa Bay Devil Rays, who are barely mentioned). But Burns transgresses in a few ways that deeply hurt his work.

One is the use of Barnicle, a former Boston Globe columnist and current MSNBC contributor, as the Everyman to tell the Red Sox story. Barnicle’s a controversial guy, in Boston and nationwide. He lost his job at the Globe in 1998 after two plagiarism charges (which makes him a strange hero for a work that tells a sad tale of cheating). On his radio show in 2004 he had to apologize for racial insults to Secretary of Defense William Cohen and his wife, Janet Langhart, who is black (which likewise makes him an odd choice for a story that celebrates racial diversity and progress). In 2008, he forever endeared himself to feminists by describing Hillary Clinton as “looking like everyone’s first wife standing outside a probate court.” (That might make him a fit for a film that features only two women, but more on that later.)

Barnicle’s professional troubles are never mentioned, but more remarkably, to my knowledge no media report has made the connection between Barnicle’s star turn and the role of his wife, Anne Finucane, the Bank of America chief marketing officer credited with the B of A’s sponsorship of “Tenth Inning.” Finucane’s role is no secret; she’s been quoted about the bank’s Burns partnership and photographed at gala events with the filmmaker. But it’s undisclosed within the project, and given Barnicle’s (to me questionable) centrality to “Tenth Inning,” something there feels off.

Even more disturbing, given that the steroid scandal frames “Tenth Inning,” Burns’ beloved Red Sox avoid its taint. While Burns shows a few photo galleries of steroids users, from former White Sox and Giants pitcher Wilson Alvarez to Yankees star Alex Rodriguez — he conspicuously leaves out Red Sox star David Ortiz, who was named by the New York Times and other media as one of the players who tested positive for steroids in 2003. (It’s hard not to think that Manny Ramirez is briefly shown only because he left the Red Sox for the Dodgers.)

Finally, “Tenth Inning” replays a major (for me) “Baseball” flaw: Again, only two women speak — Doris Kearns Goodwin (only as a Red Sox fan) and the journalist Selena Roberts, who covered the steroids mess for the New York Times. Growing up, I knew women fans were as passionate (if not as numerous) as men, since my mother and grandmother made me a Mets fan as a toddler. But when I asked Burns why he only featured two women commentators in 1994, he got defensive, telling me: ”Other people that we interviewed didn’t do as well. But I’m very happy with the film. I think this is essentially a male sport.” Since “Baseball,” there have been three female assistant general managers, Kim Ng of the Los Angeles Dodgers, Jean Afterman of the New York Yankees and Elaine Steward of the Boston Red Sox (Steward is now VP and club counsel). And Ng interviewed for the G.M. job with the Dodgers and the Mariners; maybe it was tokenism, but a lot of interviews with minority managers were tokenism back in the day. Still, but Burns couldn’t find more than two women to talk about these 15 years? That’s disappointing.

I also have to say “Tenth Inning” missed some of the joy of “Baseball,” and baseball. I admire Burns’ courage in focusing on the steroids mess; he had the cooperation of Major League Baseball on this project, providing film and video footage, but MLB can’t be happy with his focus — and yet I feel like it shut out the fact that the vast majority of fans, even after those troubling years, are still fans. I know I looked away from evidence that Bonds was juicing — I saw his head get bigger, literally, not figuratively after 1998 — from my seats in AT&T Park as well as occasionally from the field and dugout, when I sporadically covered the Giants. But I always argued — correctly — that Bonds was unfairly punished for not working sportswriters, even before the steroids controversy, and I still believe that he was made a scapegoat for an era when fans, owners and MLB management looked away from what they knew, either to play the game, profit from it or just love it.

Fans loved the game all through those years, scandal or no scandal, and we still do. Barry Bonds had the most beautiful swing I ever saw and probably ever will see — before and after 1998 — and I’ll always be grateful for that, even as I love my 2010 San Francisco Giants with their working-class heroes and pair of 20-home run stars. I’m not sure Burns captured that love and joy for anyone but Red Sox fans in “Tenth Inning.” In a year of thrilling postseason diversity — Cincinnati! Texas! Maybe even San Francisco! – when every race but one will have been decided in this glorious final week, that’s an unfortunate oversight in a work that otherwise celebrates baseball with the great love it deserves.

(Correction: An earlier version of this story said there were only two assistant general managers in Major League Baseball, leaving out Jean Afterman of the New York Yankees.)