As Jane Addams, the founder of Chicago’s Hull House, lay in her bed recovering from surgery in the spring of 1916, she received a visit from Theodore Roosevelt. Addams had campaigned for Roosevelt and his Progressive Party in 1912. Now Roosevelt had come hat-in-hand to ask Addams to endorse the Republican presidential ticket in the fall election. But Roosevelt wasn’t her only electoral suitor. President Woodrow Wilson, also eager for Addams’ backing, had sent her 60 long-stemmed American Beauty roses, a wish for a speedy recovery, and also an implicit request for her endorsement.

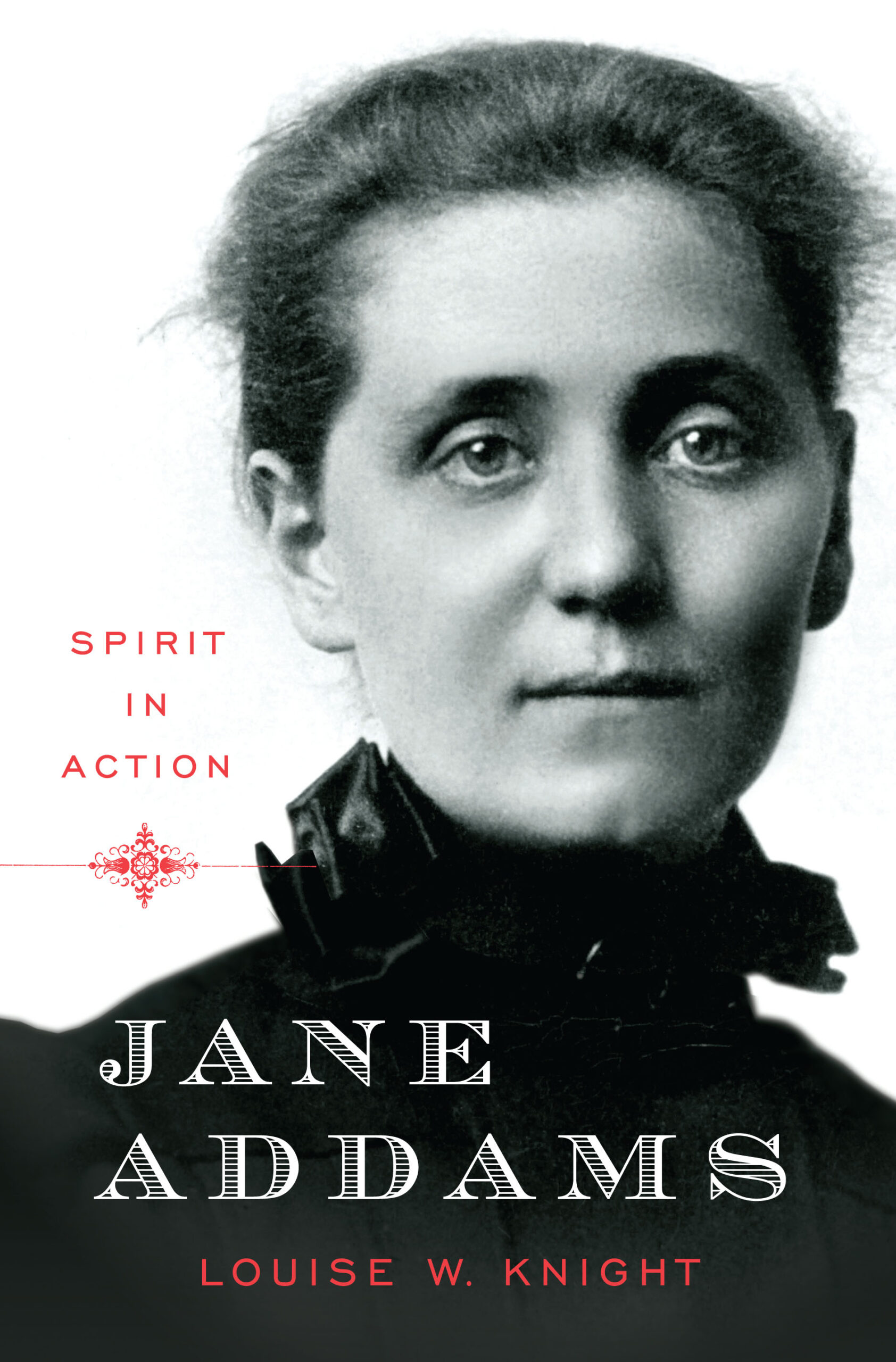

Who was this woman, who could turn two of the most powerful men in America into political courtiers? Louise W. Knight’s riveting new biography, “Jane Addams: Spirit in Action,” rescues this fascinating figure from the twilight of textbooks and polemics to bring her complex career into view. A prominent progressive, Addams was an adviser to no fewer than eight presidents, a bestselling author, and a woman who rejected the strictures of Gilded Age America, becoming along the way one of the most beloved and reviled women in American history.

Who was this woman, who could turn two of the most powerful men in America into political courtiers? Louise W. Knight’s riveting new biography, “Jane Addams: Spirit in Action,” rescues this fascinating figure from the twilight of textbooks and polemics to bring her complex career into view. A prominent progressive, Addams was an adviser to no fewer than eight presidents, a bestselling author, and a woman who rejected the strictures of Gilded Age America, becoming along the way one of the most beloved and reviled women in American history.

Knight devotes the first part of the book to Addams’ first, transformative journey — from diligent daughter to creator of the institution that would forever define her. From an early age, Addams (1860-1935) had a desire to “fix the world,” finding inspiration in Ralph Waldo Emerson, abolitionist John Brown, and suffragist Lucy Stone. Though she yearned to study medicine, her father wouldn’t hear of it, limiting her education to what was available to students of the Rockford Female Seminary. Like many women of the 19th century who had been introduced to the world of ideas, Addams found returning to life under her father’s roof small and confining.

When Addams was 20, her father died unexpectedly, leaving his daughter heartbroken, but now independent — and wealthy enough to pursue her own interests. She spent the next decade trying to figure out what to do with herself, and in true upper-middle-class style, she embarked on two extended trips to Europe. In between galleries and operas, Addams toured Toynbee House, a settlement house by the London docks, which showed her what could be done to help the poor. An idea had begun to crystallize.

Back in Chicago, she found a rundown mansion in the 19th Ward, an immigrant neighborhood home to Germans, Irish, Italians and French-Canadians. Using her own money and drawing on her network of women friends, she opened Hull House in 1889. “Her large vision,” writes Knight, “was to create a place that would nurture universal and democratic fellowship among peoples of all classes. It was a distinctly social, not political, ideal.” Although her work was inspired by her Christian faith, Addams made a conscious decision not to proselytize. It was a practical decision — she wanted all who came through Hull House’s doors to feel comfortable — but also borne of her own disdain for those who insisted there was only one way to be a Christian. By 1901, the Hull House included the mansion, as well as an art gallery, clubhouse, children’s building, quarters for working women, and a coffeehouse. Seven thousand people came through its doors each week.

Hull House made Addams famous, giving her the opportunity to put her ideas to work on a larger scale. Good with a pen and a skilled orator, Addams began speaking out on local and national issues. She soon cast aside her disdain for politics, becoming adept at lobbying for concerns close to her heart: accomplishing women’s suffrage, abolishing restrictive immigration policies, improving poor working conditions, and achieving equality for African-Americans.

What made Addams so effective at promoting her vision was her ability to build coalitions. She abhorred conflict — a product of her childhood growing up in a testy household — and could always see both sides to an issue. She also had the rare ability to invoke a sense of responsibility for the greater good without resorting to guilt. Knight, however, resists portraying Addams as a leader of the progressive movement, and rightly so: “[S]he was actually more like a surfer riding the long, splendid wave of political energy that progressives across the country were creating.”

By 1917, Addams had become a beloved public figure, but her opposition to American involvement in the Great War turned her into an object of scorn. Addams’ pacifism, according to Knight, was a natural extension of her philosophy: “To her a government at war was a government seeking to harm its citizens: it not only required them to kill other human beings and to risk being killed but redirected tax dollars from social programs into military expenses and restricted citizens’ right to free speech.” Ignoring charges that she had turned traitor, Addams became the guiding force behind a series of women-centric peace groups. In 1931, when she received the Nobel Peace Prize, her reputation had recovered enough that critics again sang her praises.

One of the pleasures of this book is Knight’s portrayal of Addams’ private life and the web of friendships that sustained her. Knight treats with great care Addams’ relationship with Mary Rozet Smith. Committed to each other for four decades, the two women shared a devotion they regarded as being equal to marriage. Knight relies on letters between the women to reveal the contour of their relationship, while declining to speculate on what happened behind closed doors.

Books about people who devote their lives to grand causes can wind up feeling like one long meal, full of fiber but short on flavor, with a side of hagiography. But Knight has resisted the urge to turn Addams into “Saint Jane,” revealing instead a complicated woman elated by the small pleasure of talking with a child at Hull House or deeply troubled by the brutal personal attacks prompted by her pacifism. The result is a biography that’s not only vital for students of American history, but highly readable, a poignant rendering of the woman and the era she helped to shape.