Thomas Carcetti was determined to turn Baltimore around. A well-meaning man whose fatal flaw was political ambition, the fictional mayor in David Simon’s "The Wire" quickly concluded that the best way for him to help Baltimore was to become governor. Then he would have the resources to aid Baltimore’s schools and address the city’s drug violence. Then he could really solve his city’s problems.

Carcetti’s bid for governor was ultimately successful, but the critical question remains unanswered at the end of the series: Will his commitment to Baltimore fade as Maryland’s suburbs and exurbs place their own demands on the new governor? The only hint we have is the beginning of Carcetti’s victory address, which, like the acceptance speech of an Oscar winner who thanks his agent and God but not the wife we see clapping in the audience, seems to be missing something: "It’s a great day for Democrats and it’s a great day for Maryland," he says. Baltimore must have winced.

Competition between ambition and principle is nothing new in American politics. But more than any other political transition, the decision to move from mayor to governor involves sacrificing nuts-and-bolts policymaking for an office that, while better resourced and higher profile, is shackled by the competing and often opposed demands of urban, suburban and rural constituents. Mayors are ensnared by a nasty contradiction, the Carcetti dilemma: remain mayor with the mandate but not the resources to improve urban life, or take a shot at the governorship and win the resources but lose the mandate to help cities.

This dynamic is on display this year, with a number of current and former mayors -- 12 as of the end of August -- competing in gubernatorial races. The idea of the city as a wedge issue, a bipartisan tactic with a history of effectiveness, is also on display -- and helps explain why few mayors have gone on to lead their states. Yet many mayors, knowing the odds, are still trying to follow in Carcetti’s footsteps.

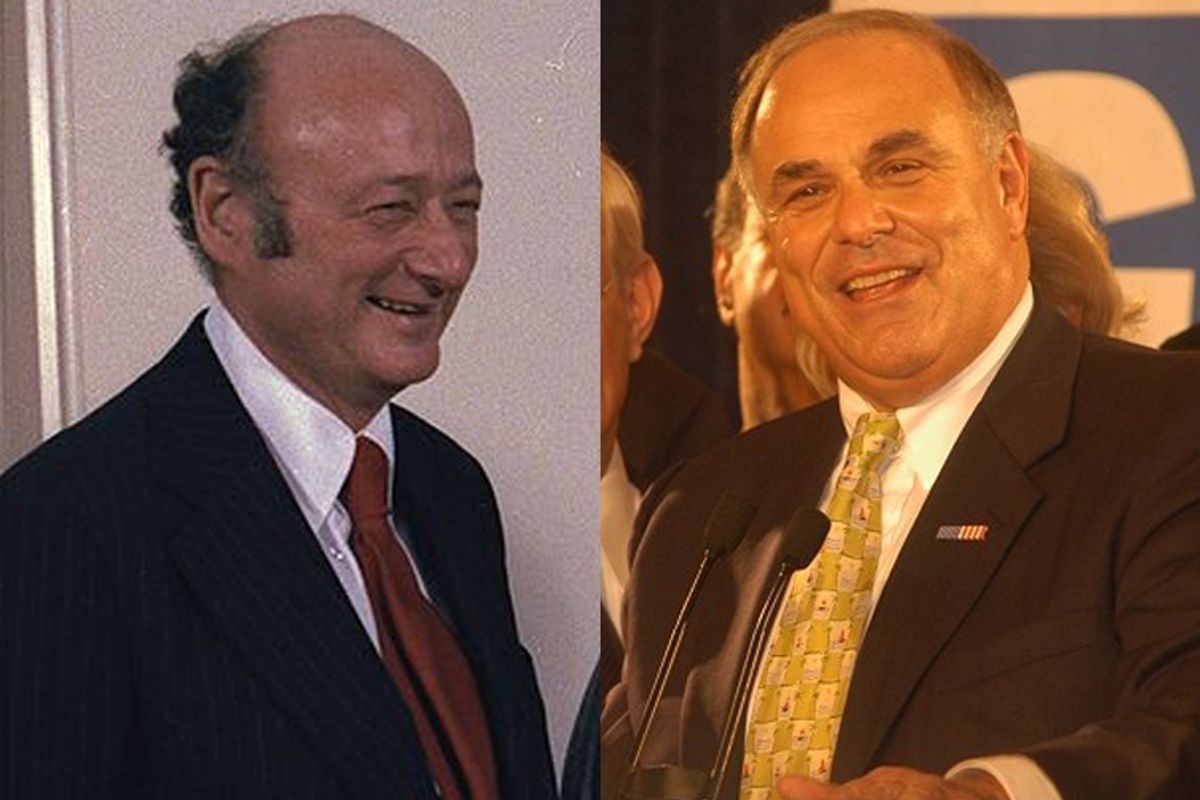

If they succeed, they will be giving up something unique in American politics. Joel Rogers, a professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who has founded organizations focused on both state- and city-level policymaking, calls being mayor "a total gas ... You're known everywhere. Your decisions touch people directly. You deal with an incredible variety of issues. You get instantaneous feedback." He points out how much fun Ed Koch had as mayor of New York. "He found it endlessly intoxicating," Rogers says. Pennsylvania Gov. Ed Rendell, the former mayor of Philadelphia, admitted to me that the mayoralty is so fulfilling that he might have forsaken the governorship and remained mayor had he not been term-limited.

The governorship, in contrast, is a drag. Governors travel all the time and knock heads with provincial, and often unruly, state legislatures. The suburban and rural preferences of the legislatures, whose urban membership has declined precipitously over the years, can be particularly jarring for a mayor-turned-governor.

Bill Bishop, author of "The Big Sort," adds that the heterogeneity of state, as opposed to city, electorates makes policy achievement extremely difficult. Consensus is elusive and partisanship dominant. "The likelihood of success is diminished," he says.

The mayor-turned-governor is a rather rare occurrence in American government. Between 1981 and 2006 the position held by a governor prior to gubernatorial office was a local elective position of any sort only 8 percent of the time.

Academics have a particularly harsh outlook on mayors’ prospects for higher office. Sayre’s Law, named for a Columbia University political scientist, instructs that mayors, particularly New York mayors, "come from anywhere and go nowhere." An oft-cited 1963 study of mayors’ upward mobility is even less circumspect: "Mayors throughout the United States have little in common but the lack of a political future -- that they are, as a profession, predestined to political oblivion is a historical fact." Larry Sabato’s classic 1983 overview of the American governorship, "Goodbye to Good-time Charlie," all but dismisses the mayoralty as a steppingstone to the governorship.

While some recent studies wonder if the mayoralty is a career destination rather than a career dead end, the literature suggests that if the governorship is your goal, any statewide office would serve you better than a term as mayor.

One of the reasons for this is that mayors are immediately confronted with suspicion when they step onto the statewide stage. Tim Ceis, a Washington state political operative and former Seattle deputy mayor, says that "The mayor of a central city is hated for various reasons. The city is looked at as the powerhouse. The rest of the state assumes their tax revenue supports the city though the opposite is often true."

Rendell told me that mayors are handicapped when they run for governor. After almost eight years as governor, he says, there are still people who worry that his policy decisions are designed to benefit Philadelphia to the detriment of other parts of the state.

Rival campaigns often play up such suspicions, peddling the worst stereotypes about urban decline to associate mayor candidates with high crime rates, poorly performing schools and corrupt Big City political machines.

Former Maryland Gov. Bob Ehrlich, a Republican, employed so-called scary city tactics in his 2006 campaign against current Gov. Martin O’Malley, the former Baltimore mayor on whom "The Wire’s" Carcetti is partly based. These ads, researchers at the University of Maryland noted, painted a "bleak picture of O’Malley’s Baltimore as a fenced-in urban nightmare with residents locked on a fixed path from early childhood to a dreary future and possibly even a life of crime."

The use of the city as a wedge issue is bipartisan. In the same 2006 election cycle, Democrat Bev Perdue released an ad shown in less urban eastern North Carolina that painted her Republican opponent, Pat McCrory, the former mayor of Charlotte, as dismissive of rural interests and overly sympathetic to the needs of the city he served. McCrory, the ad warns as the shadow of Charlotte’s buildings creeps ominously over the state, thinks "rural people" get too much highway money. McCrory had been a vocal advocate of transit while mayor, a dicey proposition for a politician seeking votes from auto-dependent suburbs and exurbs. (A similar, but more lighthearted, Perdue ad accuses McCrory of wanting to import New York City’s trash to North Carolina. The voice-over instructs, "Pat McCrory: Don’t let him dump on us.")

Candidates are reviving these same themes in the current gubernatorial election cycle.

While the self-destruction of the Colorado Republican Party has insulated John Hickenlooper, the Denver mayor and the Democratic nominee for governor, from serious attack, the Washington Times noted that his "urban liberal" label might harm him as a candidate; the Denver Post columnist Vincent Carroll questioned Hick’s preference for transit over roads; and Republican candidate Dan Maes unleashed a bizarre diatribe against the mayor’s bike-share program, attacking it as a strategy to "rein in American cities under a United Nations treaty." To make himself more appealing outside of Denver, Hickenlooper has downplayed his strongest pro-environment positions, talked about his "rural roots," and cultivated his already folksy persona with charming, somewhat flimsy advertisements.

In Texas, Republican Gov. Rick Perry’s chief political consultant tried to gin up support for his candidate with a missive that played up the urban pedigree of Bill White, the former Houston mayor who is running against Perry as a Democrat. The e-mail argued that "In this political environment no competitive state will elect a big city trial lawyer, anti gun, sanctuary city promoting, Clinton protégé D.C. politician, let alone a conservative state like Texas." A Democratic consultant who spoke with the Dallas Morning News echoed this line of attack, worrying that Rick Perry would "try to paint Bill White as a sissified urbanite." To ensure that the contrast wasn’t lost on voters, Perry shot a coyote dead with a laser-sighted pistol while out for an early morning jog.

Membership in the Mike Bloomberg-led Mayors Against Guns coalition, not exactly the anti-gun equivalent of the NRA, has become an issue for both White and Bill Haslam, the Republican mayor of Knoxville who is running for governor of Tennessee. Worried their affiliation would play poorly outside their cities, both dropped their memberships, with Haslam accusing the group of radicalizing after he joined.

Minneapolis Mayor R.T. Rybak, who ran unsuccessfully for the Democratic gubernatorial nomination in Minnesota this year, is particularly sensitive to the dilemma mayors face. He sums up the suspicion of his candidacy outside of Minneapolis: "The pundit and professional political class just assumed that I couldn't sell in other parts of the state."

So why do mayors even bother to run for governor?

Blind ambition is a possibility -- but even the precocious Thomas Carcetti was motivated at least in part by a concern for Baltimore and its inhabitants. More likely, says Joel Rogers, it is a matter of cities’ role in American governance. "Legally," Rogers observes, "cities are creatures of states, and state governments often let them know that." Mayors who run for governor are probably concerned that if they don’t, "they’ll always be limited by people who don’t like cities as much as they do."

Cities’ inferior position in American federalism was codified in "Dillon’s Rule," an 1868 decision of Iowa’s Supreme Court that held rather biblically that "[The state legislature] breathes into [municipal corporations] the breath of life, without which they cannot exist. As it creates, so it may destroy. If it may destroy, it may abridge and control." While the extent to which cities can govern themselves varies, Dillon’s Rule essentially put cities at the whim of state legislatures and the governors that wield significant influence over them, a condition that has been exacerbated as cities have come to rely more on state than federal funds.

Without a sympathetic governor, cities can languish. Mayor Rybak, for instance, expresses frustration with Minnesota Gov. Tim Pawlenty who he says "is like a lot of cynical politicians in America today who think they can get votes by pitting people against big cities."

Gov. Rendell frames mayors' impotence in terms of resources: "You get tired of not having resources to affect health care, education, and welfare and you just decide you want to have more resources." In the end, he says, "[As governor] I’ve done more for Philadelphia in education -- 10 times more -- than in my eight years as mayor."

The Carcetti dilemma is not simply a lament for a politics that is kinder to mayors. The deeper, and more disturbing, lesson is that our current federal structure hangs cities, the economic and cultural giants that generate the majority of the nation’s economic output, out to dry. Rendell is an exception: Even the most "urbane" of governors -- even those who were mayors -- must fight against state legislatures dominated by rural and suburban interests and against the temptation to cater to suburban values when their urban roots are attacked. The city has no representative at the state level.

In this environment, urban advocates like Mayor Rybak who hope to become governor are sticking their necks out quite far indeed when they campaign on the straightforward argument that urban and rural America are interconnected and interdependent. "When you’re a big city mayor running statewide," he says, "the first thing you have to do is to remind people that the big city grew because of its connections to the rest of the state." But voters resist even this conception. After all, Rybak concludes, "the past 50 years have been about separating cities from the land around them."

The Carcetti dilemma, it turns out, is much less a critique of political ambition than it is one of American governance. Who, indeed, can champion America’s cities if not its mayors?

Shares