Remember the '90s, when we all thought we were crazy? Everyone ran out and got a shrink (New Yorkers got analysts — not just for Woody Allen anymore!). Couples' therapy became a widely chosen ritualistic precursor to divorce, aimed at clarifying for each party exactly when and how their spouse became reprehensible. The middle-aged departed on healing retreats en masse to learn about centering and recovering their inner child. The most fragile souls wound up in stuffy hotel conference rooms under the banner of Werner Erhard's Forum, where an authoritarian patriarch urged them to simply sweep away their "rackets" like so many dust bunnies.

Back then, everyone pathologized themselves and each other. We pointed our fingers at each other and proclaimed, "narcissist," "borderline," "bipolar," "passive-aggressive," "sex addict," then unloaded our anxiety over the demons flying around our heads in our allotted 50-minute sessions. Why were the people who weren't paying $150 an hour to be showered in unconditional positive regard so damn confused?

These days, the war of the sane versus the insane has usurped the political stage, both sides refusing to politely listen for another second, swapping out any agreement to disagree with an overarching proclamation that the other side is simply unhinged (and deeply stupid, to boot). With the globe in peril and abject lunatics threatening to take over the asylum, it seems we no longer have the luxury of dissecting each other's colorful assortment of dysfunctional tics.

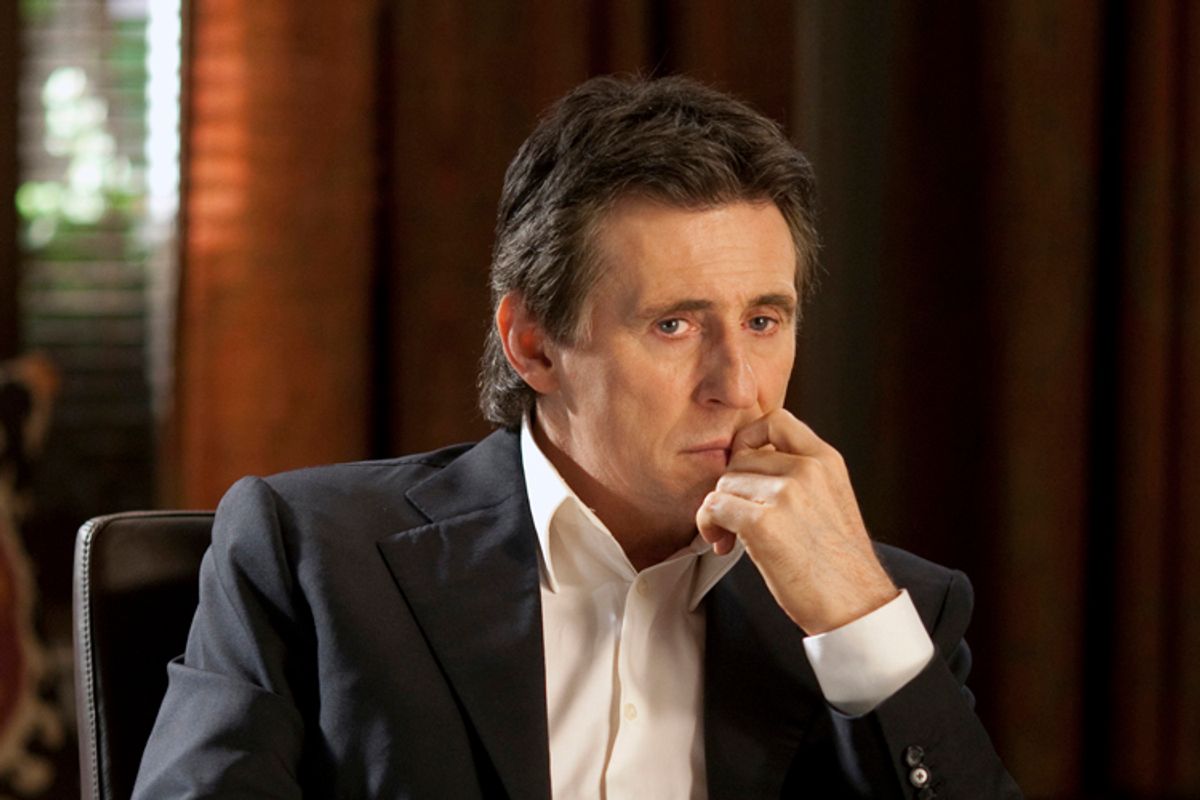

Maybe that's why HBO's "In Treatment" (premieres 9 p.m. Monday, October 25 and 9 p.m. Tuesday, October 26) feels like such an anachronism. While other dramas hurtle forward with action sequences and rapid-fire dialogue, a dizzying barrage of fisticuffs and witty quips and deep confessions flying past our heads every minute, this show unfolds with the patience and restraint of a play. We sit in the office of psychotherapist Paul Westin (Gabriel Byrne) and witness these thoughtful half-hour journeys into each patient's psyche, grappling with defense mechanisms and reflexive lies and reactive emotions along the way. Rarely do any of Paul's patients want to know the whole truth and nothing but the truth about themselves. Instead, they digress, beat themselves up, push back, roll their eyes, attribute intentions to third parties that don't exist, and generally avoid the heart of the matter at all costs.

This makes watching "In Treatment" a little bit rigorous, like solving a mystery alongside our fearless detective. As Paul tries to guide each client gently through his or her rough emotional terrain, we're presented with clues as to where the areas of resistance – and the answers – lie. Is Sunil (Irrfan Khan), a Bengali man brought to New York from Calcutta by his son after his wife died, paralyzed by a longing for his wife, or has he receded into an alienated state out of repressed envy of his son and daughter-in-law's freewheeling Western lifestyle? Clearly gay teenager Jesse (Dane DeHaan) is struggling with his sexuality, his identity, his anger at his adoptive parents and countless other issues. But does Paul have any chance of steering him away from a pattern of blaming those who love him, while leaning on and confiding in those who only want to use him? There's an undercurrent of violence and rage with these two patients that makes their interactions much more tense than usual.

In contrast, Frances (Debra Winger), a former famous actress, alternates between sweet smiles and moments of exasperation and self-doubt. She wrestles with her sister's cancer diagnosis and her daughter's abandonment, but doesn’t take any steps to repair either of those relationships. Instead, she's funneled her frustration into her work, forgetting her lines in rehearsals for a play for the first time in her career. Despite this evidence of how our avoidance can create odd side effects, Paul himself is convinced that he's developing Parkinson's disease, just like his father, which we learn in his own sessions with his new therapist, Adele (Amy Ryan). Far from the matriarchal figure and professional advisor he found in Gina (Dianne Wiest) in the first two seasons, Adele is patient but clearly skeptical of Paul's self-diagnosis, and she's resistant to his constant tests to make sure she's a therapist worthy of his time. (In their second session, when Paul demands that Adele tell him whether or not she understands his reference to Bartleby, I'm just dying for her to answer, "I prefer not to!")

Paul's shift from gentle professional to arrogant, resistant patient was always a little bit jarring, but it underscores the complexity of "In Treatment's" perspective on therapy. Instead of offering us some illusion of the ideal, nurturing therapist – an illusion that anyone who's actually been in therapy has embraced at some point – this narrative delves into the gaps in Paul's understanding as vigorously as it does with any of the other characters. Similarly, far from celebrating the work of therapy as a straightforward adventure to the last frontier of a patient's psyche, the show serves up a running critique of the therapeutic process. Paul often confuses Jesse with his son, and assumes that Jesse requires the same unconditional love and patience, to the point where Jesse, however hurt he might be by his circumstances, begins to look capable of abuse. It doesn't occur to Paul that what Jesse is crying out for, more than love, is open confrontation and clear boundaries. Jesse's mother and Paul may share an urge to avoid the darkness that Jesse continuously shoves in their faces.

If all of that seems like heavy lifting, well, it is. And as entertaining as "In Treatment" can be at times, the third season may be the most grueling of them all. It's tough to see how any of these characters will find anything remotely resembling a sense of happiness before the season is over. Unfortunately, this season may also be the most simplistic so far. While it was never even close to obvious after three episodes what characters like Mia (Hope Davis) or Alex (Blair Underwood) really needed in their lives or what emotions they were meant to sort through in order to make progress, Sanil, Jesse and Frances don't seem as mysterious or as complexly rendered. Sanil has some battle against his own desires that devolves quickly into a cliché of superego versus id, cultural repression versus indulgence, while Jesse and Frances quite obviously need to break down their defenses, open up their hearts and love a little.

It's tough to tell if it's the acting or the writing, but with Frances' scenes in particular, we're awkwardly aware of an actress performing a role, and this prevents us from viewing Frances as a real person. Granted, Frances is an actress, and maybe her therapy sessions feel like a performance, even to her. But it's tough not to feel frustrated with the very surface-level conversations she has with Paul during the first three episodes.

Frances: Ava Gardner played the part in the movie. Did you see it?

Paul: Are you worried about being compared to Ava Gardner?

Frances' remarks and Paul's responses feel predictable, and offer none of the almost furious blurring of boundaries and emotions that occurred in Mia's segments last season. With Mia, and with Sophie and other brilliant character portraits of the first two seasons, it was impossible not to become utterly engrossed in the setbacks and triumphs of their struggles for happiness.

What's also strange is that all of the characters, Paul included, are less likable and harder to empathize with this season than in seasons past. Sanil is occasionally poetic and funny but mostly a little flat, Jesse is so sarcastic and bratty, checking his cell phone and pouting and storming out, that it's hard to sit through his sessions at all, and Frances feels at once familiar and uninteresting. Paul's current fixation on Parkinson's doesn't lead anywhere intriguing either – eventually he'll either figure out that it's psychosomatic, or he'll have to deal with his diagnosis, but either way this battle isn't something that leaves a lot of room for interpretation. I almost wish that the show would go back to having four patients, not three, so that there were another character in the mix who might offer the same layers of inner conflict we've come to expect here.

Instead, during much of the first few episodes, we feel just like Paul does when he tells his new therapist, Adele, "Listen to you! You sound like a textbook."

Shares