Two years ago, President Obama came into office declaring his intent to seek bipartisan cooperation as he addressed the dire economic woes facing the United States. But with the exclusion of a tiny handful of "moderate" Republican senators, he was utterly rebuffed. From day one, Republicans attacked his stimulus plan remorselessly, derided his bank reform initiatives as "anti-business" and called him "socialist" for such actions as rescuing General Motors. Even measures that normally receive routine Republican support, such as tax breaks for small businesses, or the extension of unemployment benefits during the middle of a recession, were opposed at every turn.

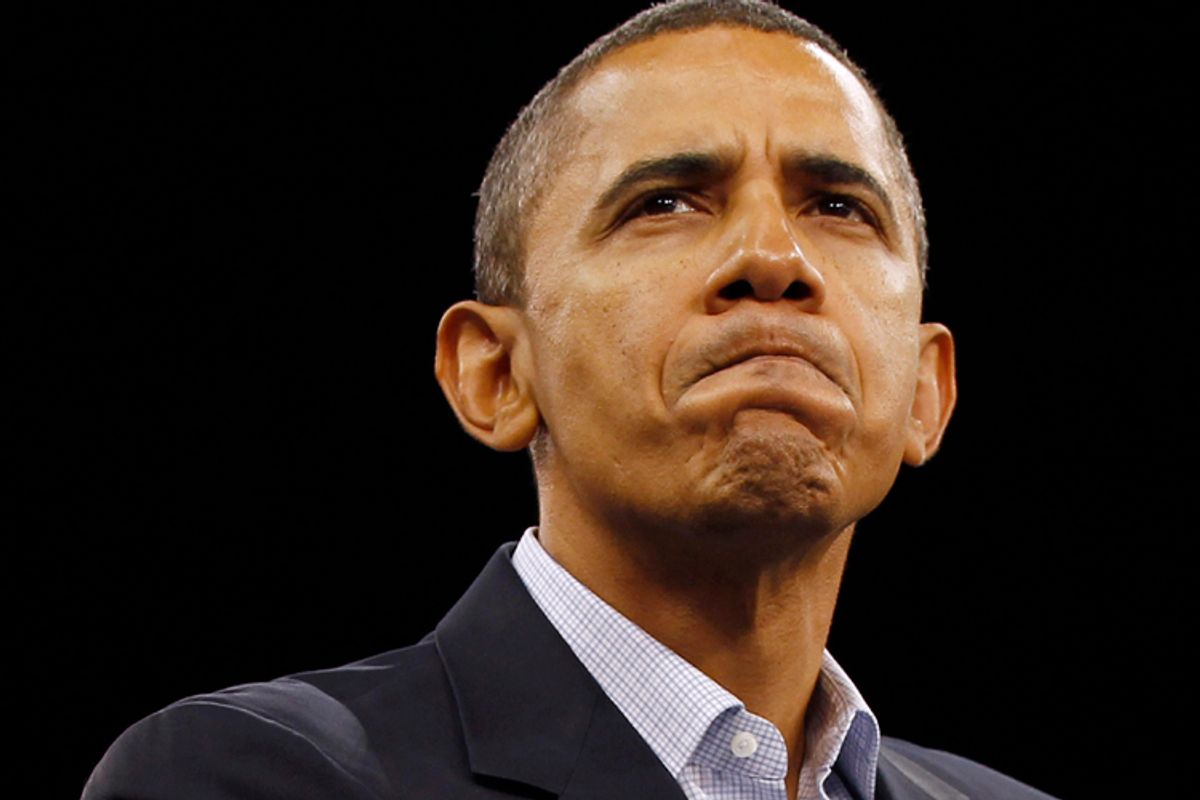

So now the Republican "wave" has swept over the landscape, the Democrats have decisively lost control of the House and witnessed their majority in the Senate substantially weakened. But unemployment is still high and the economy is growing at a snail's pace. The question is thus posed: What is the economic policy agenda for the White House from here on out? Will Obama pull in his horns, cowed by defeat, and look for ways to work with the likely new Speaker of the House, John Boehner? Or will he decide that there is no point in continuing the attempts at accommodation that got him nowhere in the first two years, and conclude that he has no choice but to become more aggressive in figuring out ways to get the economic moving again, help the most vulnerable Americans in a time of hardship, and tackle the grim reality of growing income inequality?

In practical terms, will Obama try to raise taxes on the wealthy, boost infrastructure spending, and directly employ government power to create jobs, while protecting the consumer from the depredations of Wall Street, or will he swivel his focus and energy to the supposed number one priority of conservatives: reducing the scope and size of government?

To some extent, the question is moot. The most likely scenario for the next two years is gridlock. There is little hope for major legislation of any kind moving through Congress. Further fiscal stimulus is out of the question. Instead, Obama is more likely to spend the next two years fighting off attempts by House Republicans to roll back the achievements, such as they are, of his first two terms. The grim truth is that, outside of anything Bernanke's Federal Reserve decides to do, the window for effective economic policy-making is closed, for now.

But symbolically, Obama can still set a tone. His actions in the next few weeks will tell us much. He has yet to appoint a replacement for Larry Summers as Director of the National Economic Council. If, as some have predicted, he ends up picking a CEO for the job as part of an effort to prove himself more Wall Street-friendly, he will send a clear signal that the "anti-business" jibes have taken their toll. If, as hinted late last week, he abandons his effort to allow the Bush tax cuts for the wealthiest Americans to expire, the move will mark another obvious retreat. And if he suddenly restyles himself as a fiscal conservative, aiming to bring government spending under control, he will have declared outright surrender.

But what would be the point? On Tuesday night, the New York Times reported that on Wednesday, the president would hold a press conference "where he is expected to call for both parties to put aside the vitriol of the last several months and work together to restore the nation's economy." Perhaps such boilerplate is simply de rigeur for a party leader whose party gets walloped in a midterm election. But it also is remarkably reminiscent of his rhetoric upon initially taking office, and therefore, just as unlikely to be realized in any meaningful way. If there's any lesson that Republicans are going to take away from this election it is that vitriol and intransigence and total unwillingness to cooperate work -- politically, at least, if not in terms of getting anything done that meaningfully improves the welfare of Americans.

Nothing has changed in that dynamic. Republicans are already telling us that the people have "spoken" and will surely interpret the change in electoral fortunes as a rebuke of Obama's economic policy up to this point. But their success still hinges on ensuring Obama's failure. They will be less willing than ever to compromise, if such a stance is even conceivable, given that they already were "the party of no." To attempt to seek cooperation in such an atmosphere is a fool's game.

One of the most dispiriting data points from last night's election was exit polling revealing that voters who blamed the banks for the state of the economy were voting for Republicans. Even if you believe Obama was too easy on the banks, this represents a remarkable Democratic failure, since the banking lobby has now swung its financial support to Republicans, with the explicit agenda of rolling back regulatory reform, loosening government oversight, and fending off any increase in their tax burden. The banks are the big winner in his election, in part by capitalizing on populist anger against the banks!

Perversely, one could almost argue that one message sent by the Republican upsurge is that American voters don't think the government has done enough for Main Street. The White House response should therefore be to look for ways to prove that it is actually on the side of the working man. In the new political reality Obama's options will be limited: Ultimately, his freedom of an action may boil down to a willingness to be negative, to resolutely veto anything that conservatives manage to get through the House and the Senate. But if he wants to have any chance of winning in 2012, it's hard to see how cooperating with the GOP will get him there. He already tried that. It didn't work.

Shares