When artist Jasper Johns was mourning the end of his relationship with Robert Rauschenberg, he took one of his famous flag paintings, made it black, and dangled a fork and spoon together from the top.

Hidden symbols in Johns' "In Memory of My Feelings," tell part of story, curators said. Color from the relationship is gone. A fork and spoon elsewhere in the painting are separated. Here we have a coded glimpse into a six-year relationship that was rarely acknowledged -- even in Rauschenberg's 2008 obituary.

The Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery is decoding such history from abstract paintings and portraits in the first major museum exhibit to show how sexual orientation and gender identity have shaped American art. The installation, "Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture," opened Saturday and is on view through Feb. 13.

"There's been an entire history hiding in plain sight," said Portrait Gallery historian and curator David C. Ward. "Telling the history of art without the history of gay people is like telling the history of slavery without mentioning black people."

Many have avoided the subject, he said, out of politeness or homophobia.

Ward said he was surprised to discover more gays were fired from federal jobs during the Red Scare of the Cold War era than suspected communists. In that political climate, he said, many modern artists turned to abstraction and coded language to portray themselves and those they loved.

The exhibit, funded primarily with private donations, comes 20 years after the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington canceled a retrospective of photographer Robert Mapplethorpe's homoerotic images for fear of a backlash from Capitol Hill.

The Smithsonian's exhibit is different, Ward said. Indeed, there are few pictures of men kissing, but curators carefully chose many of the 105 pieces for what's not obvious at first glance.

An 1898 Thomas Eakins painting, "Salutat," opens the exhibit, portraying a boxer's bare body -- but in a way that challenges what it means to be male, considering its creation during the testosterone-charged 1890s, Ward said.

A 1914 painting of "Men Reading" by J.C. Leyendecker used for Arrow shirt ads treads a thin line between portraying two men as acquaintances or lovers. The artist modeled one character on his male partner.

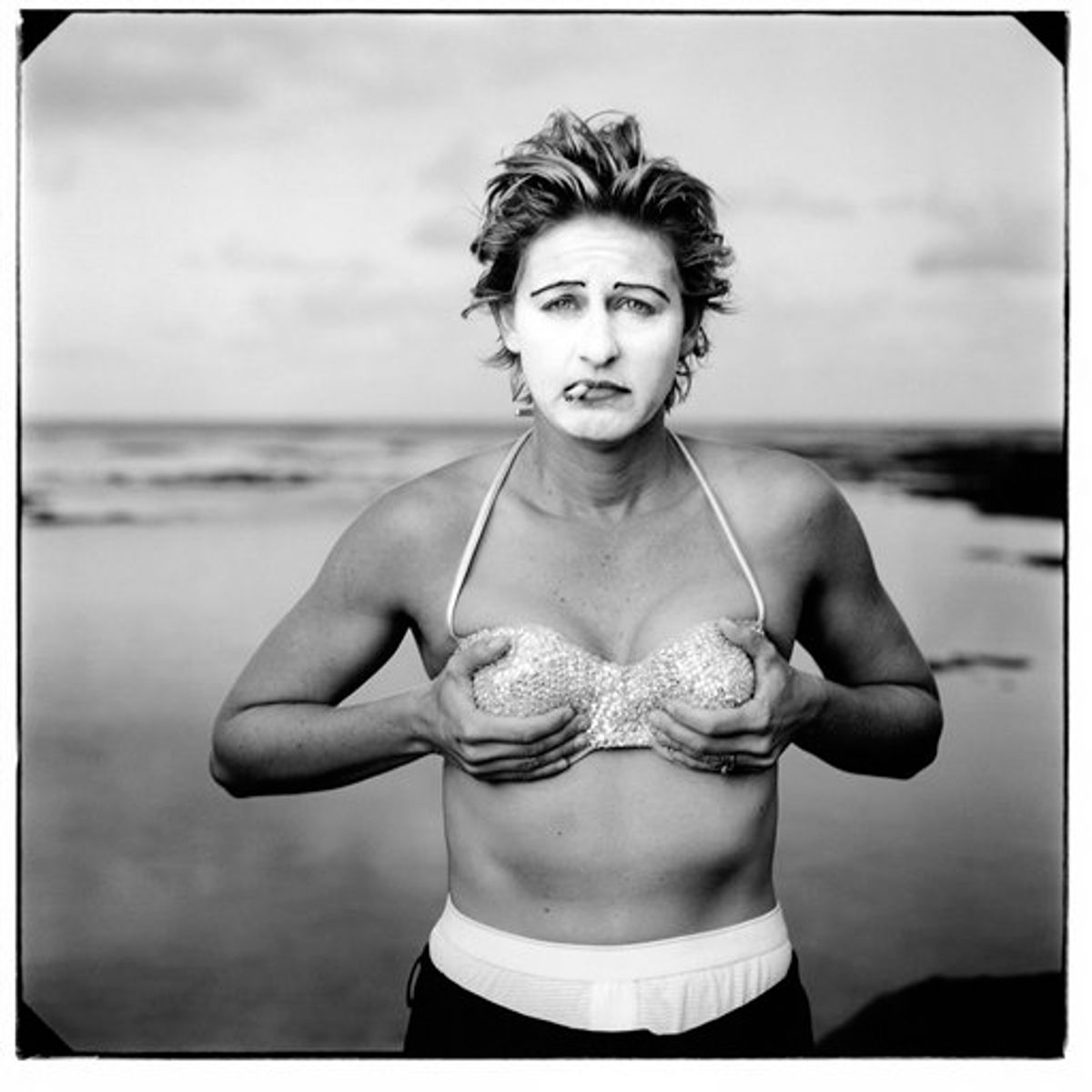

Fast forward to 1998 with an Annie Leibovitz portrait of Ellen DeGeneres meant to capture the ambiguity of how the actress presented herself to the public before she came out.

Other portraits show male nudes, which are still less common in museums than portraits of bare women.

While the images are mostly tame, curators know such a show at the publicly funded Smithsonian Institution could draw scrutiny. Co-curator Jonathan Katz of the State University of New York at Buffalo said he tried for 15 years to mount a similar exhibit in New York City but found no takers.

"How did we get to a point where the banking world is more progressive than the museum world?" he said, noting many corporations already offer benefits to same-sex partners. "This was the last acceptable prejudice."

------

Online:

National Portrait Gallery: http://www.npg.si.edu/

Shares