It all begins with a grudging favor. Beatrice Nightingale, a high school teacher from Manhattan on a much-anticipated tour of Europe, agrees to look up her wayward nephew at the request of her rich bully of a brother. It's the early 1950s, and there are foreigners all over Paris, strangers who fall "into two parties -- one vigorous, ambitious, cheerful and given to drink, the other pale, quarrelsome, forlorn; a squad of volatile, maundering ghosts." The first group are, of course, Americans like Beatrice's nephew, Julian, young people who "called themselves 'expatriates,' though they were little more than literary tourists on a long visit, besotted with legends of Hemingway and Gertrude Stein." The second are the war's traumatized detritus, and anything but nostalgic: "They were not postwar. Though they had washed up in Paris, the war was still in them."

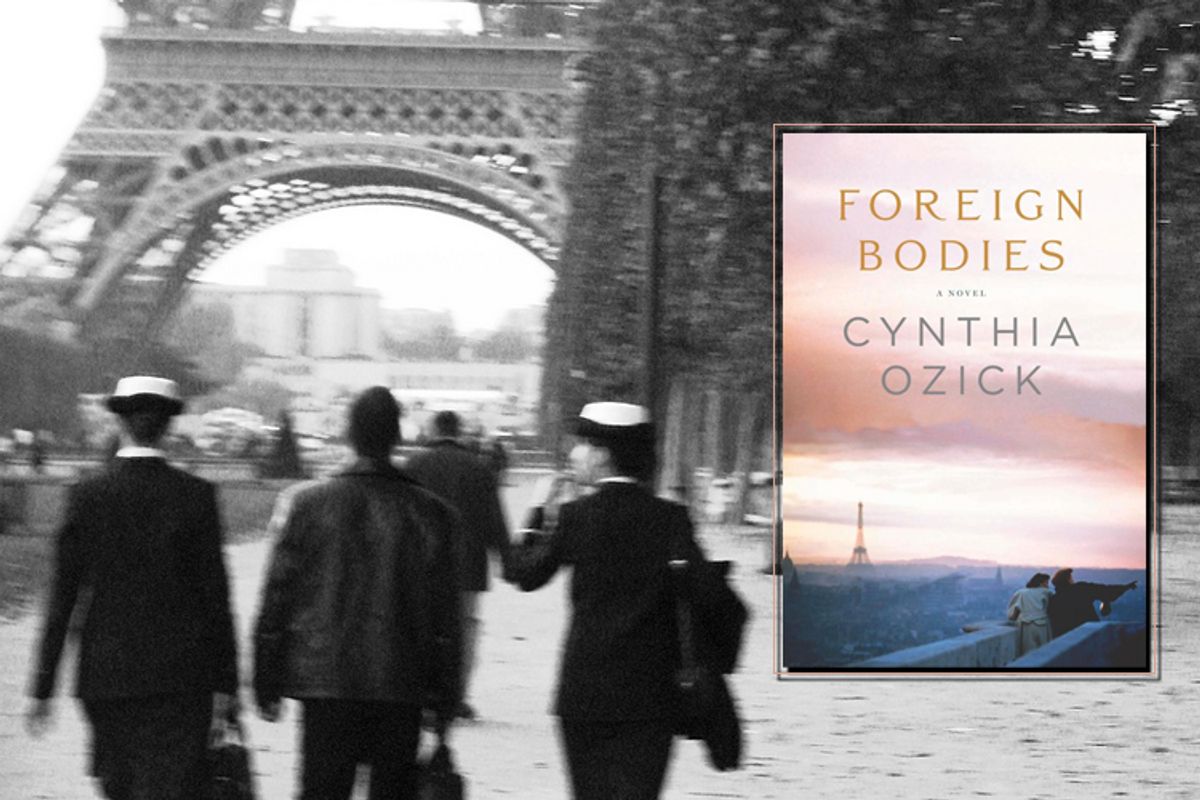

Slim, keen and astonishingly compressed without being the least bit cryptic, Cynthia Ozick's new novel, "Foreign Bodies," dissects that inexhaustible theme, the queasy encounter of America and Europe, the old world and the new, the past and the future, via the trials of one disintegrating American clan. Although she lives a quiet and apparently contented life, Beatrice, against her better judgment, allows herself to be sucked into her brother Marvin's flailing attempts to keep his family together. Julian -- and eventually his sister, Iris, who becomes an exile as well -- is rude to his aunt, and, it turns out, entangled with a haunted-looking older woman who wears long sleeves in warm weather, a detail whose significance isn't lost on Beatrice. Meanwhile, Marvin's WASPy wife, sequestered in a posh California sanitarium, sends her sister-in-law haughty, accusatory letters.

None of these indignities, however, can quite match the many brusque, imperious missives Beatrice receives from Marvin; his letters give the novel much of its brio, especially in its early chapters. "Don't tell me about your so-called job," he writes, "they'll never miss you. You do what you do and you are what you are because you never had the drive to be anything else." Why does Beatrice comply? She tells herself it's because she feels sorry for her brother, which she does, but passages dipping into her own youth and the history of her failed marriage reveal a lifelong ambition to investigate "things that start out hidden." She begins her task as an "ambassador," but she ends up as a "spy."

"Foreign Bodies" is acknowledged to be based on Henry James' "The Ambassadors," albeit loosely -- as, say, Zadie Smith's "On Beauty" is based on "Howard's End." This is one of those fortuitous homages that will appeal to the hardcore Jamesite without necessarily alienating the equally passionate Jamesophobe. Here are the same intricate moral puzzles that drive every classic Jamesian narrative, and the subtle consideration of art and its worth. There are, for the aficionado, several inside jokes and allusions to other James novels and stories. You won't, however, encounter the clause-tortured sentences and oblique evocations of class that drive James detractors nuts. There's even, I fancy, a ribbing of the Master's late style in how Iris regards her brother's justifications for his behavior:

This was the familiar Julian, sidling into vapor. Iris felt she could put her finger all the way into such talk and never get hold of a single fact. His thinking wouldn't come clean, it ran around corners, it was all melting words, you couldn't pin it down.

American energy and innocence versus European worldliness and despair: Can they ever meet without incomprehension and alienation? That's the question at the heart of "Foreign Bodies," but the divide isn't purely national or geographic. Beatrice started out with the last name of Nachtigall (changed because her loutish students couldn't pronounce it). She and Marvin are the progeny of an unambitiously bookish Jewish shopkeeper and his driven, hustling wife. But while Marvin kept the name, he took after his mother and tried to leave everything else behind. Beatrice knows her brother will explode when he finds out what kind of woman his son has taken up with, and that's exactly what he does: "I finished it off, it wasn't supposed to get into the next generation, and it never did, I stopped it right from the start ... I can't have one of those, not in my own family."

Wandering through the Louvre, Beatrice imagines Marvin, who manufactures aircraft, scoffing beside her, "belittling what he couldn't plumb. Amnesiac America, America the New. What's new is good, workable, efficient. Engineered." Then she thinks, "But what he was capable of!" Lili, the woman Julian loves, on the other hand, is so harrowed by her losses she wants only to "sit under a gourd" in the Holy Land. In the lovers' conversations, "he croaked out his California, the land of unknowing ... She bled out her Transnistria, where too much was known, and nothing he could imagine." Although this couple ends up as a paired emptiness, Ozick doesn't believe the cause of synthesis is entirely hopeless; the solution, however, will come from an unanticipated quarter.

These are obviously large and weighty themes, yet Ozick encompasses them in an effortless 230 pages, in prose of arresting vigor and clarity. To begin one of her novels is to be seized immediately by her indelible voice, but they are never mere exercises in style. The thing Beatrice and so many of the other characters in "Foreign Bodies" are all trying to do, that unification of old and new, Jew and Gentile, America and the venerable Western culture it inherited and has (ambivalently) carried forward? That's just what she does.

Shares