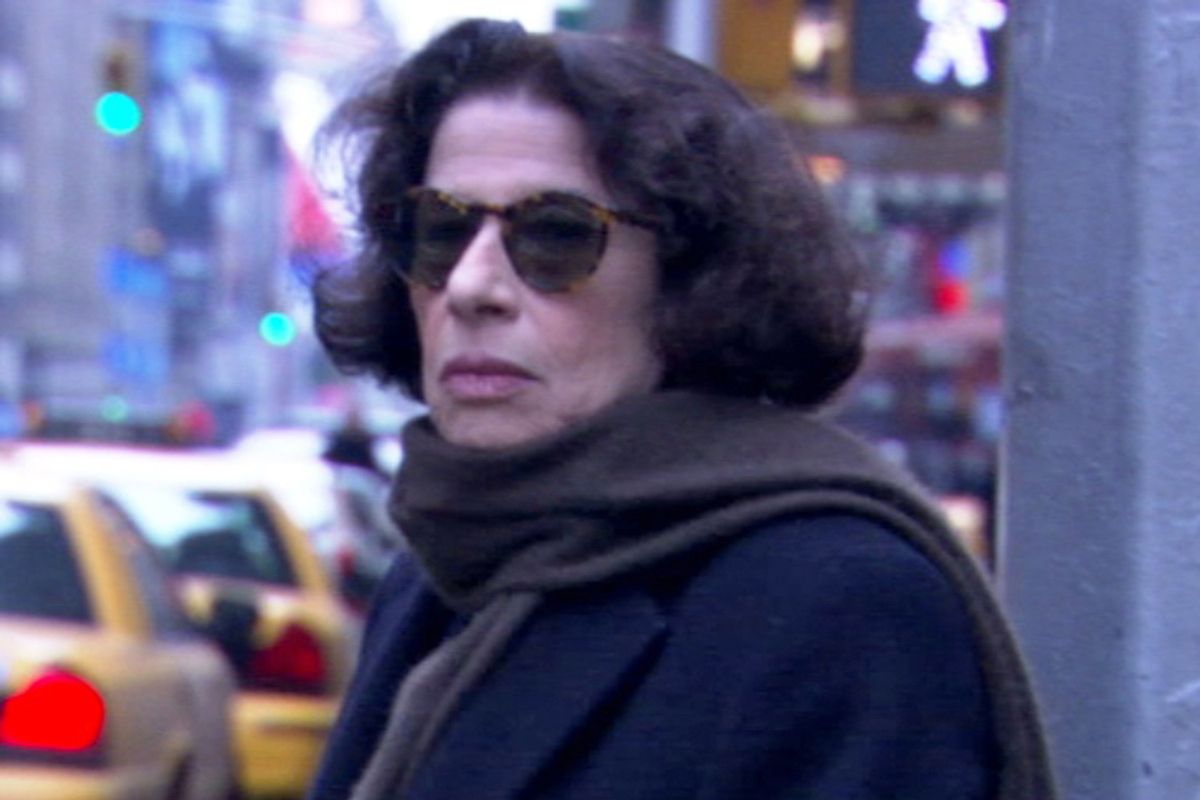

At the start of "Public Speaking," Martin Scorsese's documentary on Fran Lebowitz, you might find yourself wondering, "Just how much adoration does an author of exactly two books deserve?" After all, the woman hasn't written a book for almost 20 years, yet she's heralded as one of the singular wits of her generation.

But then, if you take the time to flip through the pages of "Metropolitan Life" or "Social Studies" yet again, you'll find two truly great books that stand the test of time. And how many truly great books do most authors have in them?

The answer to that question, of course, is zero. Or as Lebowitz herself puts it when speaking to a roomful of young people, "There are too many books, the books are terrible, and it's because you have been taught to have self-esteem." This is Lebowitz's distinct talent: making elitist contempt sound charming.

Toni Morrison, a friend of Lebowitz's, puts it a little differently. "You seem to me almost always right," she tells Lebowitz. "But never fair."

"That's why," Lebowitz responds. "I'm always right because I'm never fair."

Most of us secretly wish that we could be as right and as unfair as she is. But the world has changed a lot since "Metropolitan Life" was first published in 1974. Being unfair isn't nearly as acceptable as it used to be. Today, people demand prose that is polite, respectful, nonjudgmental, and that never employs terms, phrases, suggestions or hints that could offend any segment of the population. People demand prose that isn't prose, in other words.

Contrast that with almost any assertion made by Lebowitz in "Metropolitan Life" or "Social Studies": Jews make good stand-up comedians. Sports are "dangerous and tiring activities performed by people with whom I share nothing except the right to trial by jury." Communism is unpleasant because "I do not work well with others and I do not wish to learn to do so." Children "tend to be sticky" and "respond inadequately to sardonic humor and veiled threats."

"Public Speaking" (premieres 10 p.m. Monday, Nov. 22, on HBO) is also packed with Lebowitz's clever observations, the most gratifying of which may be her reflections on the ways our culture has changed since her books were first published. "An audience with a high level of connoisseurship is as important to the culture as artists. That audience died in five minutes," she says, referring to the AIDS epidemic. These days, Lebowitz says, "everything has to be broader, more blatant, more on the nose." The problem? "Too much democracy in the culture, not enough democracy in the society."

Lebowitz's real strength, though, lies in explaining the different social classes to each other, either in her books or in Scorsese's film. In "Social Studies" she includes a "Glossary of Words Used By Poorer People" including meatloaf ("A gloriously rough kind of pate") and overworked ("an overwhelming feeling of fatigue, exhaustion, weariness. Similar to jet lag"), and outlines the trivializing effects of the international jet-setter ("What, after all, is London to a man who thinks of the whole Middle East as just another bad neighborhood and the coast of South Africa as simply the beach?").

In "Public Speaking," it's clear that, although Lebowitz might mingle with elites, her underlying affections lie with the common man -- as unsuitable as she might find his pants or his penchant for installing wall-to-wall carpeting in bathrooms. When the topic of how New York City has changed over the past two decades arises, Lebowitz says, "When a place is too expensive, only people with lots of money can live there. That's the problem. You can like people with money, hate people with money. But you cannot say that an entire city with people with lots of money is fascinating. It isn't."

Even if her writers block continues for another three decades, Lebowitz herself remains undeniably fascinating. Scorsese's documentary offers us a long overdue taste of her unique, queasily accurate perspectives on our culture -- always right, never fair and never disappointing.

Shares