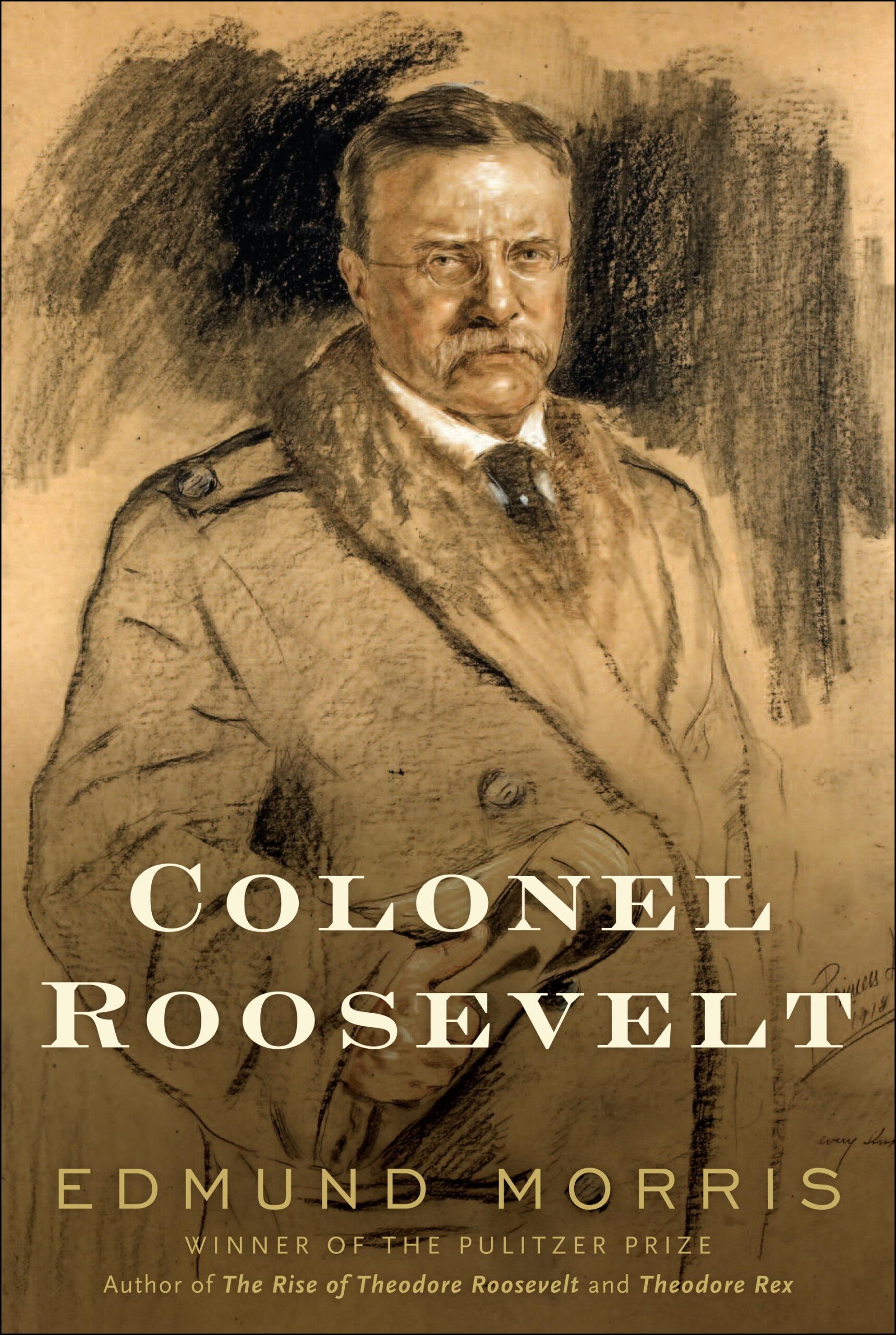

Edmund Morris, the Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer of Theodore Roosevelt (and the author of a critically panned biography of Ronald Reagan), has returned with the third and final volume of his Roosevelt biography. “Colonel Roosevelt,” with its descriptive and narrative power, its thorough exploitation of sources, and its interplay of man and nation, may be the best biography ever written about the life of an American president. It fascinates, in much the same way that Roosevelt’s editor at ‘Metropolitan Magazine” described the impression “TR” made on people: “all showing some signs of having passed through a tidal moment in their lives.”

Readers of “The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt” were engrossed by Morris’ narrative of Roosevelt recovering from the death of his young wife and his mother by spending a year in the western badlands, converting himself from an East Coast Harvard dude into a man of action, able to connect with Americans from all walks of life. Morris, who grew up in Kenya and South Africa and has a feel for the wilderness, once again provides spellbinding accounts. The first, which opens the book, sets Roosevelt in Kenya, hunting big game and collecting specimens of plants and animals for the Smithsonian Institution. The second, which comes nearer to the end, describes a harrowing trip TR took in the Amazon basin, to chart a wilderness river for the Brazilian government — the river gets renamed Rio Roosevelt — and of course to hunt, fish, and collect specimens.

Readers of “The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt” were engrossed by Morris’ narrative of Roosevelt recovering from the death of his young wife and his mother by spending a year in the western badlands, converting himself from an East Coast Harvard dude into a man of action, able to connect with Americans from all walks of life. Morris, who grew up in Kenya and South Africa and has a feel for the wilderness, once again provides spellbinding accounts. The first, which opens the book, sets Roosevelt in Kenya, hunting big game and collecting specimens of plants and animals for the Smithsonian Institution. The second, which comes nearer to the end, describes a harrowing trip TR took in the Amazon basin, to chart a wilderness river for the Brazilian government — the river gets renamed Rio Roosevelt — and of course to hunt, fish, and collect specimens.

To brilliant effect Morris uses each trip as a device to structure meaning in TR’s life. At the end of his carefree African adventure TR sails down the Nile, closer and closer to a return to Western civilization, and he receives news about American politics that presages his coming break with President Taft. It is “Heart of Darkness” in reverse. As TR portages and paddles downriver in the Amazon, the dangers increase (unfriendly locals, a mutineer among the crew, ravenous insects, difficult terrain). Morris describes a low point in a diarist’s staccato:

“Clearing skies and baking heat. Rapids, rapids, rapids. Portages too numerous to count. Occasional fish dinners, but still no meat. Evasive tapirs. Grilled parrots and toucans. Monkey stew. Palm cabbage. Wild pineapples. Fatty Brazil nuts. Disappearance of fifteen food tins. Only three weeks of rations left.”

TR and the others gradually unburden themselves, Lear-like (in torrential rain no less) of their possessions and much of their cultural assumptions. TR’s son Kermit gets one of the crew killed through an impetuous decision on the river and almost dies himself, but in the process becomes, in his father’s lights, a real Roosevelt. TR barely makes it out of the Amazon alive.

When Morris deals with domestic politics and international crises, he makes a strong case for TR’s continued relevance. Going against a tendency of some biographers to see TR in retirement as a blustering blowhard, unable to get off the stage, Morris shows the ex-President in all his complexity, at the center of progressive thought and Progressive party politics. Morris makes a strong case that TR’s criticism of Wilson’s policies in the first three years of the war were correct, and that the nation would have been better off if it had heeded his calls for preparedness and a defense buildup. It is a serious rethinking of the pre-war years.

The Roosevelt family comes alive in Morris’s telling. Wife Edith remains as private as ever, but always loving and supportive. All TR’s sons go off to war, and Quentin, the dashing pilot, dies in combat with a German ace. TR’s grief at his sons’ injuries and Quentin’s death remains a private matter, but Morris lifts the curtain for us.

“Colonel Roosevelt” settles some scores with academic historians who pummeled Morris for his unorthodox narrative approach to his Reagan biography, in a set piece in which TR lectures at the American Historical Association:

“The imaginative power demanded for a great historian is different from that demanded for a great poet; but it is no less marked. Such imaginative power is in no sense incompatible with minute accuracy. On the contrary, very accurate, very real, very vivid, presentation of the past can come only from one in whom the imaginative gift is strong.”

With this book, Morris rests his case.