It's easy, and in many ways accurate, to say that the Pentagon, with its exhaustive new report that concludes that lifting the "don't ask, don't tell" policy poses essentially no risk to the military's effectiveness, is late to the game. After all, polls have shown for some time that a clear majority of Americans -- and even Republicans -- are fine with gays openly serving in the military.

In another sense, though, the scene on Tuesday -- a defense secretary originally appointed by a Republican president telling senators that repealing the ban is "a matter of some urgency" -- was somewhat remarkable.

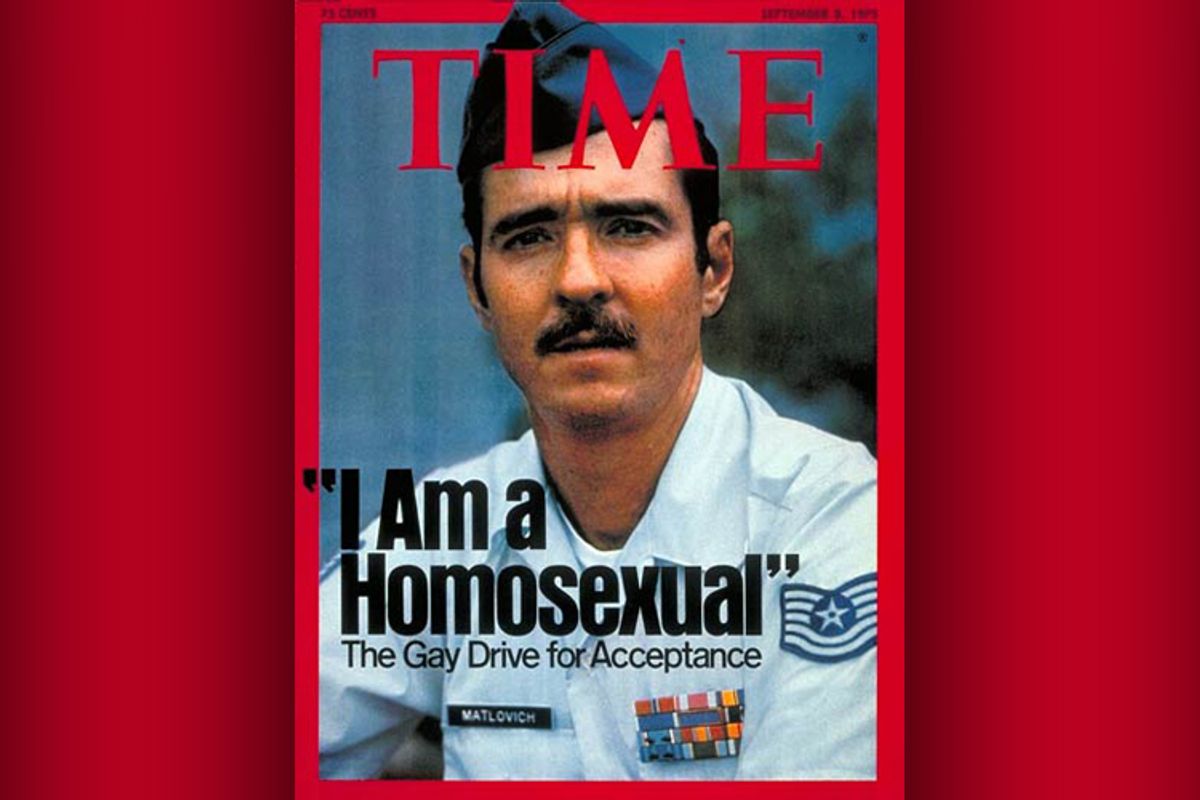

Thirty-five years ago this past September, when it was still one of the prime drivers of the national conversation, Time splashed on its cover the image of a 32-year-old Air Force sergeant who was facing a less-than-honorable discharge for being, as the magazine put it, "an admitted professed practicing homosexual." By that point, many Americans were already familiar with Leonard Matlovich, who had earned a Bronze Star and a Purple Heart during three tours in Vietnam and who was vowing to fight for his reinstatement all the way to the Supreme Court.

Time's editors had selected him for the cover of an issue devoted to the increasing prominence of homosexuals (then the customary term), who were beginning to assert themselves in ways that unsettled and alarmed many of their fellow citizens.

Less than two years earlier, the American Psychiatric Association -- following a six-year campaign by "militant gays" -- had voted to stop labeling homosexuality a mental disorder; the Federal Civil Service Commission had just decreed that, contrary to previous policy, gays were not unfit for employment; and a handful of major corporations, including AT&T, Bank of America and IBM, had even, as Time put it, "declared themselves equal-opportunity employers with regard to homosexuals." And now Matlovich was pushing even further, mounting an unprecedented legal charge against one of the country's most revered institutions.

Three weeks after the issue ran, Time printed a sample of the letters it received. The few letter-writers who were supportive all identified themselves as gay.

"I was revolted by Matlovich's face proclaiming, 'I am a homosexual,'" a Georgia man wrote. "He is a disgrace to the uniform of an honorable service." A New Hampshire woman branded the entire issue "disgusting, repulsive, lowbrow, nauseating. I'm no Victorian, but those individuals should crawl into a hole and pull it in after them -- and take TIME with them." A retired Army colonel from Florida was even more crude: "From time immemorial we have recognized yellow fever, malaria, syphilis, leprosy, perversion, degeneracy, garbage and homosexuality in about that order."

This was the atmosphere in which Matlovich set out to wage the first concerted legal challenge to the military's ban on openly gay service members, a policy that had been first enacted on the eve of World War I.

The son of an Air Force officer, a 12-year-veteran, and a staunch political conservative, he was a wholly unlikely activist. It wasn't until he was 30 that Matlovich had his first same-sex experience, an event that he described as almost instantly transformative. "I had never held another person in my arms, never kissed another person since I was a child except for family," Matlovich told Time. He quickly established a circle of gay friends and within months decided to disclose his orientation to the Air Force -- fully aware of what would come next. His superior officer thought it was a joke. "It means Brown vs. Board of Education," Matlovich replied.

Informed that he'd be discharged less than honorably, a fate that thousands of gay servicemen before him had accepted in quiet shame, Matlovich invoked his right to an appeal hearing before a three-man panel of Air Force officers. Asked on the stand to promise that he would no longer "practice homosexuality," Matlovich refused. His appeal was rejected. The discharge was official.

Then it was on to federal court, where Judge Gerhard Gesell, a liberal Lyndon Johnson appointee who had been active in the civil right movement (and who would later preside over Oliver North's Iran-Contra trial), ruled against Matlovich, decreeing that the Constitution offered no specific protection for homosexual acts. An appeals court, though, sent the case back to Gesell, noting that the Air Force's rules did state that gay servicemen, in some vague, undefined circumstances, could be exempt from discharge. The appeals court asked Gesell to clear up what, exactly, those circumstances would be. In November 1980, more than five years after Matlovich's discharge, Gesell, fed up with the Air Force's inability to offer a straightforward explanation, ordered the sergeant reinstated.

But this wasn't the happy ending it seemed. Ronald Reagan had been elected president weeks earlier, bringing in a Republican Senate with him. The Supreme Court, already tilting right after the Nixon and Ford years, would soon be even more conservative. As the Air Force began an appeal of its own, Matlovich concluded that fighting on until he reached the Supreme Court was pointless; there was no way a Nixon/Reagan court would rule for him. Offered a $160,000 settlement by the Air Force, he took it. "It was a harder decision to quit the case than it was to begin the case," Matlovich said. The first great fight to end the military's ban on gay service members was over.

Matlovich ended up dying of complications from AIDS in 1988, just shy of his 45th birthday. Thanks to his settlement in '80, he was buried with full military honors. The inscription on his tombstone: "When I was in the military they gave me a medal for killing two men, and a discharge for loving one."

The Pentagon report released Tuesday won't by itself end DADT. In fact, it's entirely possible, if not likely, that the policy will endure through the current lame duck session and into the next Congress and beyond, a function of presidential timidity and senatorial stubbornness. But it's also worth taking note of how much attitudes have changed outside Washington. Less than four decades ago, the mere sight of a gay Air Force sergeant was enough for otherwise respectable Americans to sign their names to ugly, vicious letters and to flood a major newsmagazine with them. But today, public opinion stands squarely behind that Air Force sergeant. Someday, Congress and the president will, too.

Shares