I spent almost every evening of my teen years sitting in my room. Doing algebra. Or writing essays about Julius Caesar. Or plowing through some other wholesome and useful activity that would allegedly make me into a better person. Even New Year's Eve – the one holiday where staying up late, wearing lots of makeup, and actually leaving the house are practically legal requirements – was spent at home with Mom and Dad.

But New Year's Eve was different. The rest of the year, Mom and Dad kept me (and to a lesser extent, my younger sisters) on a tight leash out of concern for our safety and well-being. But on New Year's Eve, we stayed home because of Dad's tale of the loneliest night of his life.

Dad's annual recollection of the loneliest night of his life was, and sometimes still is, the cornerstone of my family's New Year's Eve celebration. It also reminded us why we always spent the most festive night of the year barricaded in the family room in sweats and slippers.

Dad's recitation could only occur if a few necessary conditions were met. First, the TV had to be tuned to the annual bacchanal in Times Square, preferably with Dick Clark chirping happy platitudes in the background. Second, Dad never volunteered the story. Just as a child obligatorily initiates the ritual retelling of the Passover story, it was up to us kids to jump-start the narrative that made our New Year's Eve different from all others.

"Daddy! Daddy!" we'd yell as the soon-to-drop Times Square glitter ball filled the TV screen, "Tell us about the loneliest night of your life!"

Then he'd smile. And slowly begin his tale:

"The loneliest night of my life – It was New Year's Eve, 1957. I'd come down to New York with a couple other interns from Temple. I didn't know a soul in New York City.

"The other guys all had dates for New Year's Eve. They offered to set me up with someone, but I didn't have the money to treat a gal to dinner.

"So they all went off, wining and dining, And I was all by myself.

"I wandered around the city and ended up in Times Square. All those people, drunk and laughing. And I never felt so lonely in my whole life. Alone in the crowd."

Then he'd sit back. And there would be a pregnant and solemn silence. For about half a second.

"Ooh, poor Daddy! You're not lonely now, are you?"

"Yeah, you've got US!"

"Tchih!" Mom would mutter, rooting through the cupboards for champagne glasses.

And this was why, Dad would explain, we always spent New Year's Eve at home: Holidays meant nothing without loved ones nearby, no matter how much hype and glitter you threw at them. Ergo, nothing could be more meaningful than observing the passage of another year in the place we loved best, in the company of those closest to us. Even if this meant our holiday was almost indistinguishable from every other night of the year.

The key word here is "almost." The differences between New Year's Eve and ordinary nights at our place were few, but significant. First, we kids were allowed to stay up until midnight, with no lectures about the virtues of going to bed early. Second, there was almost always caviar (and champagne for Mom and Dad), to be consumed as close to midnight as possible. The very idea of feasting on exotic delicacies at that forbidden hour seemed to me almost as decadent and glamorous as going out to celebrate.

And finally, we'd always have something special for dinner before our late-night festivities. It was never anything near as elaborate as our Christmas or Thanksgiving feasts – but always something out of the ordinary.

Very often, this something special was a Chinese hot pot, a brash, blinged-out version of Japanese shabu-shabu, traditionally served in the winter.

Technically, the hot pot is just soup, but its execution makes it special: It starts as a big pot of plain simmering broth in the center of the dining table (it's kept hot over a heating unit), into which diners toss thinly sliced meat, vegetables and seafood. Diners remove these goodies as they cook and eat them with rice and dipping sauces – typically, jarred Chinese hot sauces or simple mixes of soy sauce and sesame oil.

As the meal progresses and more ingredients are added and taken from the pot, the broth grows richer and more and more flavorful – and becomes a luscious and soothing final course when everything else has been eaten.

Another thing makes Chinese hot pot special, too: It can't be made, nor eaten, by just one person. Nor is it a good choice for a first-date or business meal: Getting all those morsels of meat and vegetables in and out of the pot and into one's mouth entails lots of vulgar reaching across the table and occasionally, seagull-like theft from other diners. And no matter how careful you are, broth and sauce will end up dripped all over the table.

This means the only people with whom one can judiciously share a hot pot are those who you know will put up with you no matter what – which makes it scarily appropriate for an intimate celebration of family solidarity, observed at home in sweats and slippers.

Chinese Hot Pot

This dish is so simple and open-ended it doesn't really require a recipe, just a few guidelines.

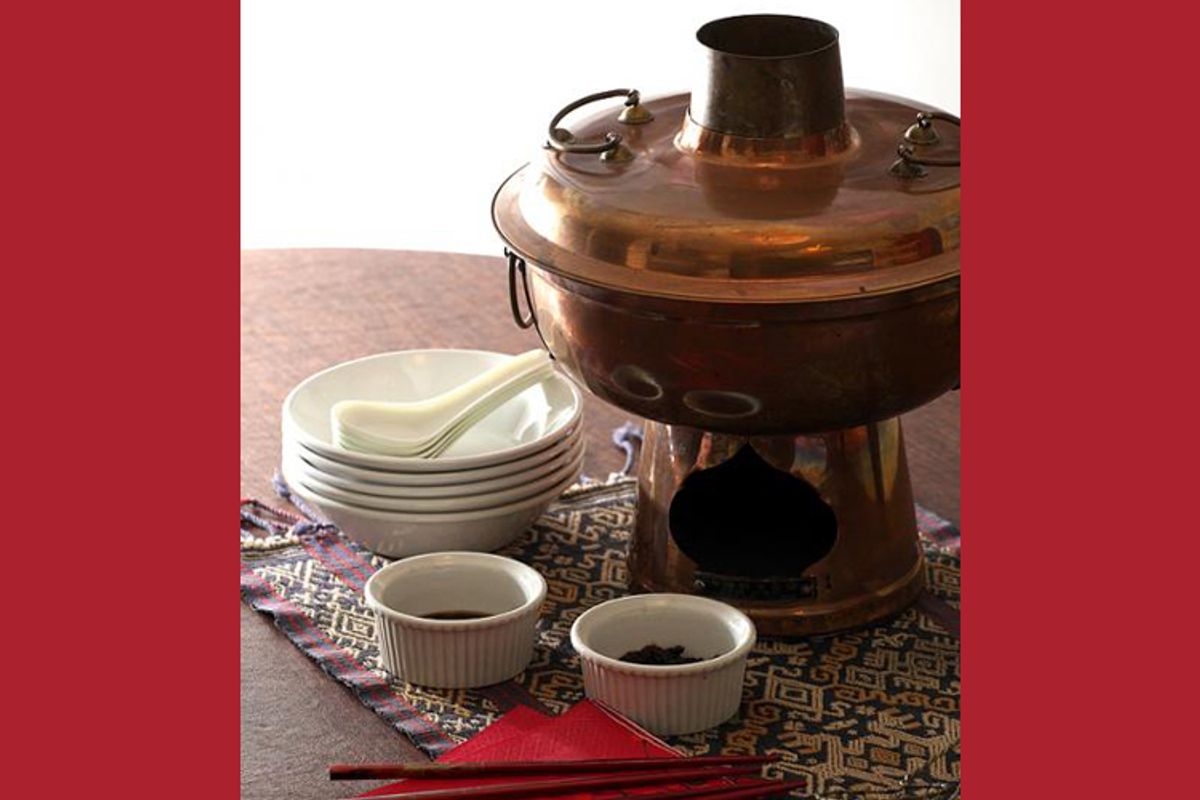

The broth: Allow about 2 cups of broth (Mom uses canned chicken broth) per person. By tradition, the broth is heated to boiling and kept hot in a special hot pot with a chimney, as seen above.

Hot coals are traditionally tucked into the base of the pot to heat the broth. But the few times my family actually used this thing, we used canned Sterno (the same stuff used to warm chafing dishes and fondue pots). In recent years, we've switched to a less-evocative but more-powerful tabletop induction unit and an ordinary soup pot to hold the broth.

The rice: Prepare about 1 cup cooked (1/2 cup raw) plain white rice per person.

The good stuff: Standard hot pot ingredients include thinly sliced beef (such as flank steak cut against the grain), thinly sliced chicken (dark meat is preferred over white by Chinese convention, and is cheaper too), cubes of tofu, fresh, shelled oysters, shelled and deveined shrimp ... pretty much any protein in bite-size pieces that cooks quickly in boiling broth. Asian markets often have packages of presliced meat and chicken specifically for hot pot; these will cut your prep time even further if you have access to them. Allow about 1/3- ½ pound of mixed meats per diner. (This can vary, of course, depending on the appetites of the individuals you're serving.)

Good vegetables to include in a hot pot are dark leafy things that cook quickly: spinach, or even better, water spinach or garland chrysanthemum leaves (available in Asian markets and every bit as fragrant and wonderful as their name suggests—and a perfect foil for rich broth and meats). Allow several big handfuls of these per diner, bearing in mind that these vegetables will wilt and shrink when cooked, so you'll probably need more than you think.

The sauces and setup: Put the hot pot full of heated broth in the middle of your kitchen table. Don't bother using your best tablecloth, or any tablecloth at all, for that matter. Turn on whatever heating unit you choose to use, and try to keep the broth at an active simmer. Set out a bowl, a pair of chopsticks or a fork, and a soup spoon for each diner.

If you can find them, also provide each diner with a hot pot basket (a small wire basket on a long handle): the baskets are used to recover cooked ingredients from the pot. If you can't find these baskets, have a couple of serving spoons available for diners to use.

Next, set out the rice and raw hot pot ingredients, as well as small dishes of Asian hot sauce (such as sriracha sauce or sambal oelek) and soy sauce mixed with a few drops of vinegar and sesame oil. Then make sure you have lots of napkins.

To serve: Place some of the meats and/or seafood into the hot broth, then some of the vegetables. Instruct diners to hold their freaking horses and try to behave themselves until the meats are cooked (this should take no more than a few minutes). Then allow them to extract whatever they want from the pot (Hey! No pushing! There's plenty to go around!), to be eaten with rice and dipping sauces.

Replenish the broth with meat and vegetables as needed. When you're out of meat and vegetables (or when everyone is too full to eat any more) spoon the broth into bowls to enjoy as a final course. By this time, it will have absorbed the savor of meat, vegetables and good conversation, and will be a perfect cap to a New Year's feast.

Shares