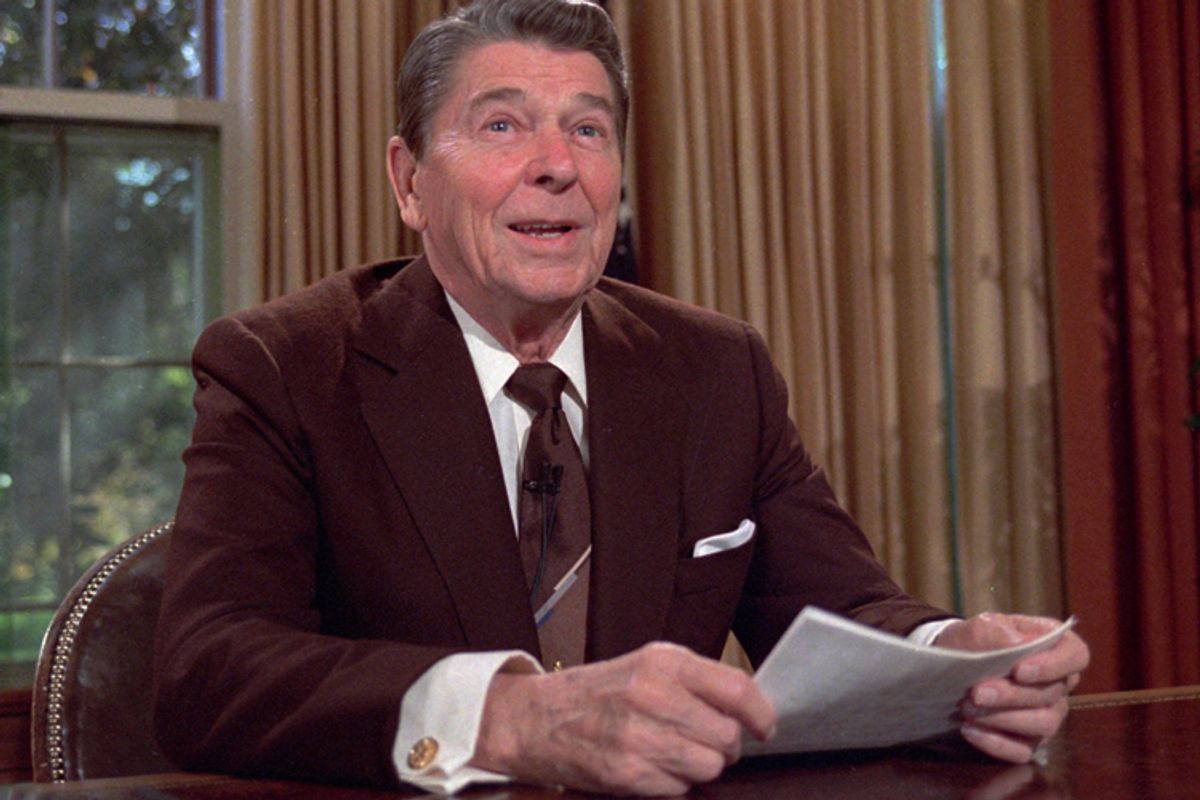

The Washington Post's Stephen Lowman has an early look at Ron Reagan's new book about his father, which will soon be released to coincide with what would have been the former president's 100th birthday. Specifically, Lowman highlights passages dealing with Reagan's struggle with Alzheimer's disease, which was formally diagnosed in 1994 (and disclosed to the public in a dramatic handwritten letter by Reagan in November of that year). The most startling revelation may be this:

[I]n 1989, doctors operating on Reagan expressed their belief he was suffering from the degenerative disease.

Ron Reagan writes that in July 1989, his father was thrown off a horse while visiting friends in Mexico. He received medical attention at a hospital in San Diego. When surgeons opened the president’s skull to relieve pressure they "detected what they took to be probable signs of Alzheimer’s disease." But no formal diagnosis was given.

By the time of that '89 accident, Reagan had been out of office for six months. But if his brain was showing evidence of the disease then, it seems logical that the disease actually would have started years earlier, back when he was in the White House.

Of course, from the earliest days of his presidency, there were those who questioned Reagan's mental faculties. At 69, he was the oldest man ever elected to the White House, and he was frequently portrayed by critics as detached, overly relaxed and generally uninterested in -- or even oblivious to -- the day-to-day details of governing. In his book, Ron Reagan makes reference to a particular incident that fueled this talk: Reagan's rambling, stumbling closing statement at the end of his first presidential debate with Walter Mondale in 1984:

Watching that debate, Ron Reagan writes, "I began to experience the nausea of a bad dream coming true. At 73, Ronald Reagan would be the oldest president ever reelected ... [M]y father now seemed to be giving them legitimate reason for concern. My heart sank as he floundered his way through his responses, fumbling with notes, uncharacteristically lost for words. He looked tired and bewildered."

A few months ago, I actually spoke with Mondale and asked him about that moment. The former vice president was a decided underdog in the '84 campaign, but in the wake of the debate, more than half of Reagan's lead vanished. It was, Mondale said, the only time in the fall campaign when he thought he had a chance to win:

After the first debate, we jumped about 8 points and we were up in 10 or 12 states. And there was a lot of concern about Reagan the person. It was nothing I said. I never tried to make this issue. But they could see it on camera. The second debate, he came back and he was confident, and he was direct and positive, and the public liked it, and they were reassured that the first debate was just an off-night for him. And that's what they wanted to know about him. Once they were assured, that's it.

If he'd had a second night like that -- if he'd done in the second debate as poorly as in the first debate, it might have opened up a real chance there. But it would have been based on their concerns about him, not where he was taking us. By that time, I knew all of Reagan's speeches and themes. And that first night, he was forgetting his themes. He started down the trip on the West Coast, and he got lost. It was something. One of the reporters told me afterward that I should have just ceded my time to him. But there's no joy in that. But if he'd done that again the second night, I think I'd have had a chance. But he didn't.

Of course, Reagan bounced back in the second debate with one of the best debate one-liners in history, giving voters the reassurance they badly wanted and clearing the way for his 49-state landslide on Election Day:

For his part, Ron Reagan writes that he thinks his father would have stepped down as president if he'd received an Alzheimer's diagnosis during his term.

Shares