If investors were as visionary as Steve Jobs has proved to be during his 35 years of tech wizardry, they might be able to figure out whether Apple can still thrive if its founder and CEO doesn't return from his indefinite medical leave.

But Jobs' prescience is a rarity, which is why doubt and anxiety will probably hang over the company until his fate is clearer.

The iPod-iPhone-iPad revolution that Jobs unleashed over the past decade should ensure that Apple's revenue and earnings keep growing for at least the next two to three years, according to analysts. What's more, Jobs has assembled and trained a savvy, hard-driving management team that should be capable of following his road map for the company.

The question is whether Apple can remain a step ahead and develop products that reshape technology, media and pop culture if Jobs isn't around to divine the next big thing.

Without Jobs, "Apple is a lot more like other companies. Its extraordinariness fades," says technology analyst Roger Kay of Endpoint Technologies Associates.

Apple Inc. announced Monday that Jobs, who co-founded the company in 1976, would take an indefinite medical leave for unspecified problems. The leave could be related to his previous bout with pancreatic cancer or his 2009 liver transplant.

For now, investors appear to be hoping for the best. Apple stock fell $7.83, a little more than 2 percent, to close Tuesday at $340.65. It recovered more than half of that loss after the closing bell after reporting strong earnings.

For the regular trading day, Apple lost $7 billion in market value, although most analysts believe Jobs' leadership and presence is worth much more to the company.

Jobs' value is difficult to gauge because of the sheer force of his personality, said Robert Sutton, a professor of management science at Stanford University who has studied Jobs and Apple. "Anyone who thinks they can estimate that is probably lying," Sutton says.

Stock market analyst Brian Marshall of investment bank Gleacher & Co. suspects people still hope Jobs will return to the CEO job that he has held since 1997. Since then, Jobs has orchestrated a turnaround that increased Apple's market value by 100 times.

Marshall and other analysts aren't optimistic that Jobs will resume his CEO duties, partly because he did not set a timetable for his return. Before he got the new liver, Jobs took a leave of absence from January through June 2009.

It's tough to gauge Jobs' current health problems because he has said so little about his past ones. He had a tumor removed in 2004 -- a rare and very treatable form of pancreatic cancer -- but never said whether it had spread to lymph nodes, nor how extensive his surgery was.

"We don't really know how much of his pancreas was removed. He may just have a remnant," and that may be causing continued digestive difficulties, said Dr. Charles R. Thomas of Ohio State University's Knight Cancer Institute.

Dr. Jennifer Obel, a spokeswoman for the American Society of Clinical Oncology and a cancer specialist at Northshore University Health System in suburban Chicago, said the prognosis is good for those with pancreatic tumors like the one Jobs had, even if the tumors spread.

"He's done extremely well living with this disease for many years," she said. "I wouldn't assume anything until he has released more information."

Apple declined further comment Tuesday on Jobs' health.

Apple barely missed a beat the last time Jobs was gone, and its stock climbed more than 60 percent as sales of the iPhone and Mac computers surged, even as the recession dragged on. That's a testament to Apple's chief operating officer, Tim Cook, who will be in charge while Jobs is away once again.

In a Tuesday conference call to discuss Apple's earnings, Cook predicted Apple will still shine.

"Apple is doing its best work ever," Cook said. "We are all very happy with the product pipeline, and the team here has an unparalleled breadth and depth of talent and a culture of innovation that Steve has driven in the company. Excellence has become a habit."

Cook has pretty much the same management team supporting him this time. The key players besides Cook include Jonathan Ive, who oversees the elegant design of Apple's products; Ron Johnson, who runs Apple's stores; Philip Schiller, the marketing chief; and Scott Forstall, who supervises the iPhone software.

It's a bench that investors would like to know better, says Jeffrey Sonnenfeld, a professor at the Yale School of Management and an expert on executive leadership.

"You only hear about Santa," he says, "but it's time that we hear more about the elves."

Cook, who has been with Apple since 1998, and Ive, who has been with there since 1992, will probably carry the biggest load while Jobs is gone, analysts say.

Partly because his role at Apple attracted so much attention during Jobs' last medical leave, Cook is better known than Ive. Apple has recognized Cook's contributions by making him its top-paid executive, with a 2010 compensation package valued at $59.1 million. Jobs limits his annual salary to $1.

But Ive has played a critical role in turning the products that Jobs envisioned into reality, said Leander Kahney, who has written books and a blog about Apple.

Apple's management team has been working together for so long that all the key executives should have a sense of what Jobs would want. And they may still be in touch with Jobs on key decisions because Jobs said he intends to remain involved in the company's strategy. Kay thinks Jobs may have planned even more in the past year than he usually does because of his shaky health.

The stakes are much higher than during Jobs' last medical leave. When Jobs left last time, Apple's market value stood at about $78 billion. It is now $312 billion, behind only Exxon Mobil among U.S. companies. Apple also is facing fiercer competition from Google, which has already threatened the iPhone with a rival software system for smart phones and is now setting its sights on the iPad in the market for tablet computers.

Jobs' greatest gift hasn't been for invention as much his uncanny ability to anticipate what people want and then demand the technology be designed in a simple way that appeals to a mass market.

"You can't really teach that," said George Haley, a business and marketing professor at the University of New Haven. "You can teach the processes, but not the insight. It takes a genius to do it right."

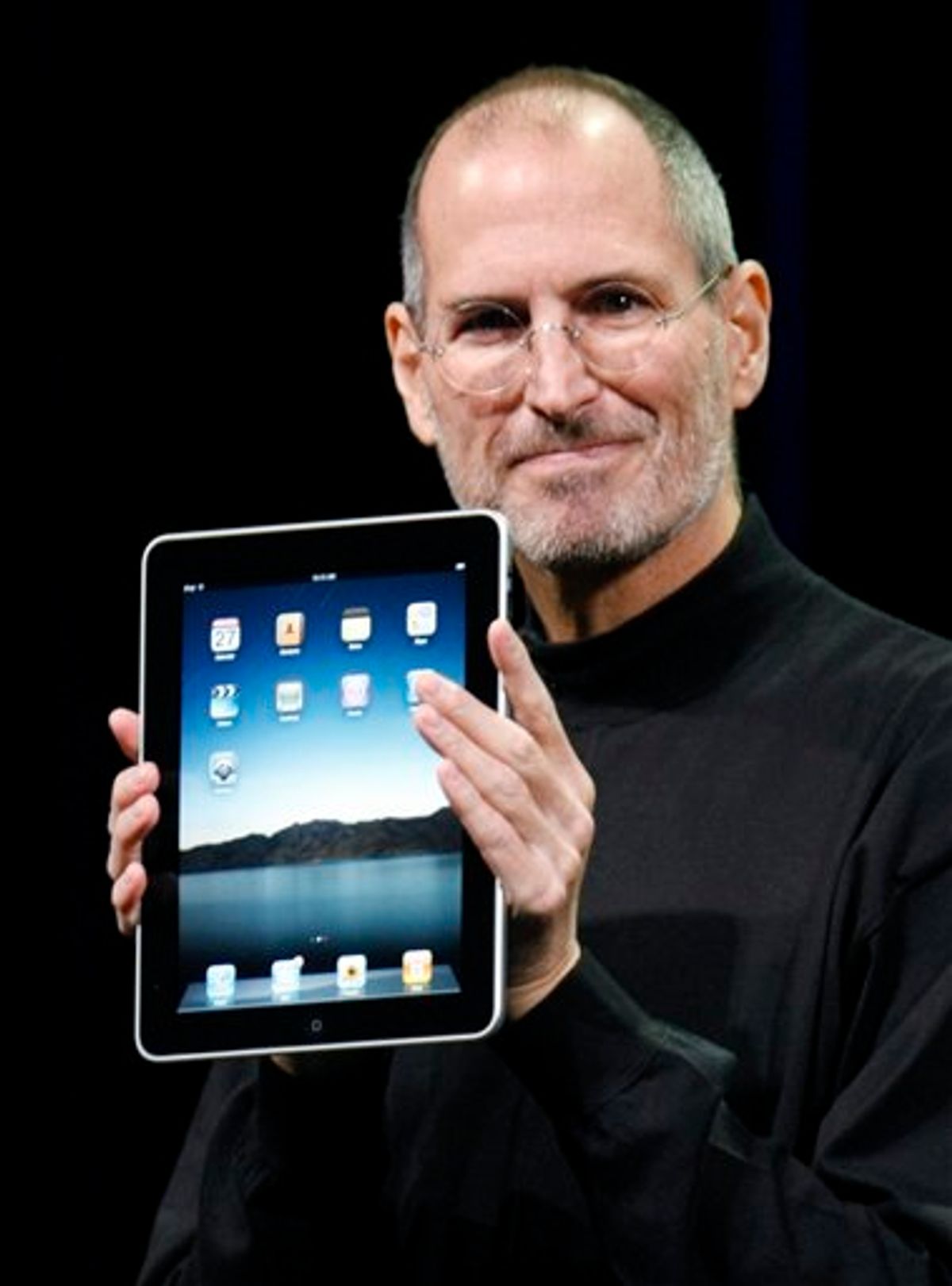

Jobs has also shown an exquisite sense for when the time is right for a product. For instance, the concept for what turned into the iPad was brought to Jobs several years before Apple had even introduced its own phone. Jobs liked the idea of a computer tablet but decided instead that its touch-screen technology would be better suited for a smaller screen at that time. That decision hatched the iPhone in 2007, a hot-selling device that paved the way for Apple's latest must-have gadget, the iPad.

Other companies developed the technology that created the computer mouse and digital music players, but neither of those innovations caught on until Jobs embraced the ideas and turned them into game-changing products.

"Steve did not invent MP3 players -- he reinvented them," said Tim Bajarin, the president of Creative Strategies and a longtime Apple watcher. "He didn't invent the smart phone -- he reinvented it. He didn't invent the tablet -- he reinvented it."

It's difficult to put a price on that kind of market intuition, particularly in an industry that changes so quickly. Almost no one had heard of Twitter three years ago or Facebook five years ago -- or for that matter the iPod 10 years ago.

Many analysts liken Jobs to Walt Disney, an entrepreneur who didn't come up with animation or amusement parks but sculpted them into a business that left an indelible mark on the world. Jobs is now the largest shareholder of Walt Disney Co., a stake he accumulated when he agreed to sell Pixar Animation a few years ago.

Just as Walt Disney Co. survived the 1966 death of its founder, Apple looks to be positioned well if Jobs doesn't return to health. But even Disney struggled for years after the well of its founder's ideas finally ran dry.

----

Jessica Mintz reported from Seattle. AP Business Writer Rachel Beck in New York, AP Technology Writers Rachel Metz and Jordan Robertson in San Francisco, AP Technology Writer Barbara Ortutay in New York and AP Medical Writer Marilynn Marchione in Milwaukee contributed to this report.

Shares