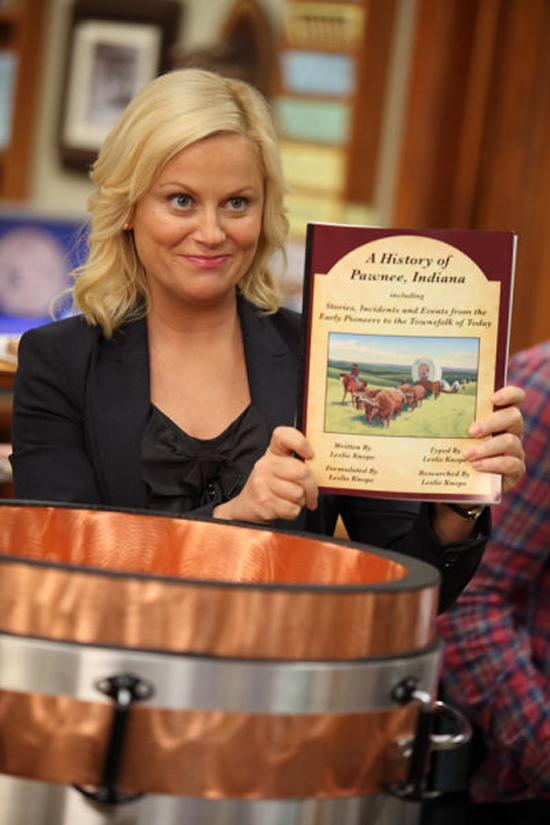

The fictional town of Pawnee, Indiana has had many slogans over the decades, and in a future episode of “Parks and Recreation,” parks department bureaucrat Leslie Knope (Amy Poehler) rattles off a sample. My favorites are, “Pawnee: First in Friendship, Fourth in Obesity” and “Pawnee: It’s Safe to Be Here Now.” There’s a whole category of slogan revealing the town’s secretly defeatist attitude during wartime (“Welcome, German soldiers”) and another commemorating a brief period in the 1970s when Pawnee was taken over by a religious cult. As is so often the case on this great NBC comedy (which premieres its third season this Thursday at 9:30/8:30 PM central), the lines are amusing on their own. But what puts them over the top is what they tell us about the mentality and history of Pawnee, and the speaker’s complex feelings about the town.

Like many small-town residents, Pawnee citizens regard their home with pride and warmth but also a nagging sense of inferiority (because the place is such a backwater) and shame (because there’s so much stupidity and strangeness on display). You sense that mix whenever Leslie talks about the place. She truly loves Pawnee; she must, otherwise she wouldn’t have devoted her life to serving it. But sometimes when she delivers Pawnee factoids there’s an anxious edge in her voice — the smiling-through-the-rage tone that people have when they tell you about their extended families for the first time, and are determined to accentuate the positive and eliminate (or at least downplay) the negative. Community-as-family and family-as-community: that’s the subject of many TV shows, including “Parks and Recreation’s” Thursday night schedule-mate, “Community.” But this series delves into it more deeply than the others, and its mix of gentle mockery and sincere affection stands it head-and-shoulders above almost any other comedy on network TV. “These people are weirdos,” says state auditor Ben Wyatt (Adam Scott), describing the citizens of Pawnee, ”but they’re weirdos who care.”

“Weirdos who Care” could have been the tagline of “Parks and Recreation.” From Leslie, with her faintly deranged optimism and “I Love Lucy”-style penchant for disastrous last-minute improvisations, to bright-eyed hustler Tom Haverford (Aziz Ansari), who can barely get through a day without plugging his swingin’ bar The Snake Hole, to Parks Department head Ron Swanson (Nick Offerman), with his awesome mustache, sleep-fighting disorder and hyper-macho affectations (“I’m surrounded by a lot of women in this department, and that includes the men”), the citizens are indeed weird (the polite euphemism is “eccentric”). The only close-to-ordinary people are nurse-turned-parks-and-rec-volunteer Ann Perkins (Rashida Jones) and department consultant and white-bread playboy Mark Brendanawicz (Paul Schneider), who left town at the end of season two to take a job with a construction company.

But those characters don’t set the tone for the show. For the most part, “Parks and Recreation” is a taxonomic study of the American kook, non-lethal variety — and it’s dedicated to proving the hypothesis that everyone’s a bit off once you get to know them. Ben Wyatt and his partner Chris Traeger (Rob Lowe) seemed on first glance to be “normal,” anchor-type characters. But Ben turned out to be a former child prodigy who was elected mayor of his hometown at age 18 and impeached shortly after; Chris is a relentlessly upbeat fitness freak whose pet phrase is “Good job!” and who compares his body to a microchip: “A grain of sand could destroy it.” When we met Ann’s useless, soon-to-be-ex-boyfriend Andy (Chris Pratt), he seemed a standard-issue lump of man-meat, but as the series wore on, he revealed himself to be a clueless rocker-wannabe, an epic doofus, a hopeless romantic, a demented man-child mentally stuck somewhere around age 10, and a latent idealist who becomes fanatically committed to any cause that happens to cross his path. Thursday’s premiere finds Andy and Ron coaching the two remaining teams in a parks and rec junior basketball league whittled down by budget cuts. Andy believes in the mission completely even though he knows nothing about basketball except that winning is great and that the winning coach is supposed to get drenched in Gatorade. (He pours it on himself.) ”When I look one of these kids in the eye and he calls me ‘coach,'” Andy says, “that’s how I know I agreed to be a coach.”

The series attains maximum oddness whenever Leslie presides over a public meeting, and we realize that the town is filled with spiritual cousins of Leslie and Ron and company. The episode that airs two weeks from tomorrow, “Time Capsule,” is one of the show’s best – a distillation of what makes “Parks and Recreation” so endearing. It starts with a “Twilight” fan trying to get a set of Stephenie Meyers’ vampire novels buried in a Pawnee time capsule and ends with a cross-section of the citizenry packed into a meeting hall arguing for and against the inclusion of particular items. Leslie lays down a few ground rules, then adds more when it becomes clear that the citizens aren’t thinking about the edification of future Pawnee residents, but about how they can immortalize their fetishes and feelings by burying them in the dirt. They seem to view the Pawnee time capsule as a democratic version of the great pyramids that pharaohs used to build as insurance against public amnesia. Citizens demand inclusion of the Bible, David Lee Roth’s autobiography, and the cremated remains of relatives and pets. The parks and rec staff isn’t much more detached; Ron’s contribution is a menu from a local diner that features his favorite breakfast, the Four Horse Meals of the Eggpocalypse. The episode briefly cuts away from the meeting; when it returns, one time capsule has become seven.

“Parks and Recreation” has a lot in common with the films of Christopher Guest (“Best in Show”) and the late, great Michael Ritchie (“Smile,” “The Positively True Adventures of the Alleged Texas Cheerleader-Murdering Mom“), right down to the pseudo-confessional filmmaking. The mockumentary format has grown stale in the forty-plus years since Woody Allen’s “Take the Money and Run” perfected it, and both versions of “The Office” have unfortunately turned it into a TV cliché. (I wouldn’t be disappointed if I never saw another character deliver exposition into the camera.) Luckily “Parks” co-creators Greg Daniels and Michael Schur (who also oversaw the American “Office”) don’t oversell, or even fixate on, the conceit that we’re seeing a record of actual events. The characters aren’t fully-rounded, psychologically deep individuals, but loving caricatures of basic human tendencies and foibles, in the Preston Sturges mode. Their asides to the camera feel more like the casual, fourth-wall-breaking confessions you’d find in a stage play, inviting us into the fiction and making us invisible, honorary citizens of Pawnee. It’s a nice place to visit.