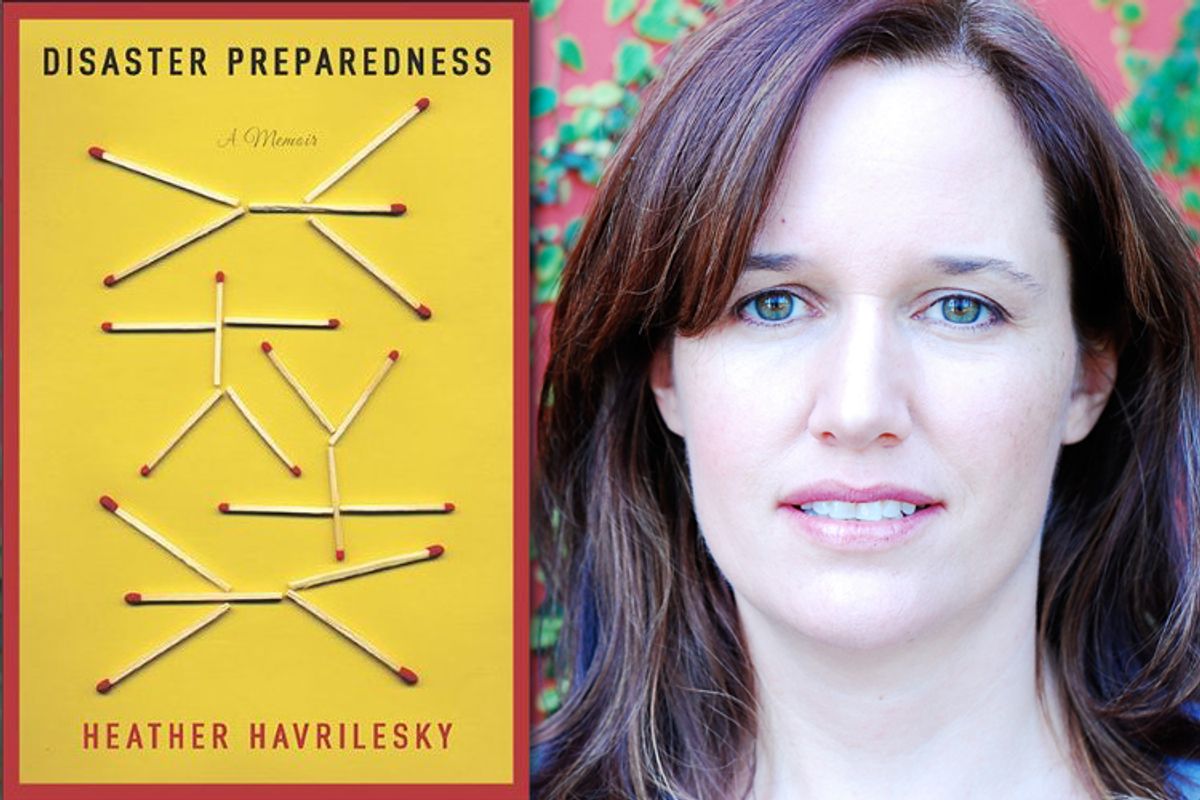

Heather Havrilesky's irreverent television reviews were a fixture on Salon. Whether she was writing about the "whoring sea donkeys" of reality TV or the soul sickness of "Mad Men's" advertising age, her pieces were as much about the world around her as the shows themselves. She has a preternatural gift for understanding human behavior, a gift she brings to her first memoir, "Disaster Preparedness," a series of finely observed tales of growing up in a tense, troubled family in 1970s North Carolina. Readers may be surprised to discover that the woman who wrote a "Deadwood" review in the voice of Al Swearengen was once a cheerleader, but her tales of feeling like an outsider -- as the sensitive youngest child, as a strange and funny teenager -- have the warmth and familiarity of an old friend.

Salon spoke with Havrilesky over the phone from her home in Los Angeles.

Because Salon readers know you as a TV critic, they may be surprised this isn't a pop culture memoir.

It's not, though I do use the disaster movies of the '70s -- "The Poseidon Adventure," "Airport 1975" -- as this backdrop for the way a lot of us grew up. But I don't think of pop culture as forming me as much as reflecting or illustrating things in my life. I mean, someone might say that's a weakness to my criticism. For someone who has similar sensibilities, I think it's a strength.

I'm wondering: Did you watch TV much as a kid?

Oh, yeah. After my parents got divorced, especially, when my mom got a full-time job. I'd take the bus home from school when I was 10, fix myself a little snack, sit down on the couch and watch three hours of TV until my mom got home.

I think a lot of us had that experience, of television as the baby sitter. What did you watch?

I watched everything. "Starsky & Hutch," "The Love Boat," "Fantasy Island," all the syndicated shows. It's weird because kids are super scheduled these days. I don't think it was great that I watched hours of TV a day, but I kind of liked that decompression time. TV still fills that role in my life.

The first half of the book focuses on your parents' divorce, but it's very steeped in the culture of the '70s. What were the weird things about growing up in the '70s?

The first thing that comes to mind is the fact that you opened the door and let your dog run into the world and then you called it to come home and you pretty much did the same thing with your kids. No one was there to say, don't do that. Having to make mud pies for entertainment sounds a little desperate, but God I loved making mud pies. We spent a whole summer making up fake TV shows and commercials. The '70s were a very interesting time of lax parenting strategies, but there were so many great things about being ignored.

When you write about your parents' divorce, there's a suggestion it rips your life apart, but my parents hated each other and the divorce was the best thing that happened to us. I had a better relationship with my dad after the divorce, and I don't think I ever knew my mom before the divorce. Once she was in charge, this new person was unveiled. She was so much happier.

There's been so much personal writing about divorce. What were the things that you thought other people had missed or that were different about your experience?

What I thought was original about my parents was the dramatic flair of their fights and the degree to which they really couldn't stand each other. Today their marriage would make it a year. They were both paying the price for being born at the wrong time or something. And my dad was a spectacularly challenging person, and I wanted to capture his unique qualities and dysfunctions. He was a professor, which is a great career for a narcissist. I know what I'm saying sounds harsh, but the book is a twisted way of honoring him. He was a provocateur, an extreme wit who could be heartless and capricious. I was extremely sensitive and emotional, and I think he taught me techniques for dealing with the world that were a little sociopathic, but they've gotten me through a lot of crazy things.

The chapter about your father, "Sting Like a Bee," is one of my favorites. You evoke your father in a way that’s both challenging and loving.

My dad was incredibly lovable and in a certain way more accessible than my mom. He wore his heart on his sleeve. You want a reader to understand the beautiful things but also the tough things. When people say, "My mother was a saint," all you can think about is, no, she wasn't.

There was one description of your father that reminded me of Don Draper -- how charming he was, how he dated so many girls. I thought about how insightful your "Mad Men" reviews were, and I had to wonder if you see parts of your father in Don Draper.

Sure. Whenever you see elements of Don Draper's past you get the flavor of what it's like to grow up under the hands of people who didn't even consider feelings when raising their kids. There's this de facto emotional neglect that took place for the whole generation, and "Mad Men" is the story of a person facing a brand-new world and trying to get up to speed with the times. That was my dad in a nutshell.

It's been said that all autobiography should contain at least one mortifying disclosure. What, to you, is the most embarrassing disclosure of this book?

When I was writing it, and even after the book was final, I remember thinking the most embarrassing thing was writing about losing my virginity. It's absurd now. It's almost like, everyone in my high school is going to read this and know what a loser I am! But the truth is that everyone loses their virginity at some point, and it's usually not very cool or romantic. It's a very common experience. In some ways, that may be the most universal experience I had.

I think I was attracted to mortifying details every step of the way. There is nothing I like reading less than a piece of nonfiction about a person's discovery or growth and yet you're not left with one embarrassing detail about that person? How is that even possible? That, I find horribly frustrating and annoying.

Let's talk about that story of losing your virginity. Can you just tell us a bit about what was going on and what happened?

It's pretty simple. My closest friend had a crush on a guy. I slept with him on an impulse. The next day, I walked into the Eddie Bauer type of place where the guy worked. Here's the guy, looking scared, like I might kill him. I said, "About last night, it's really no big deal, but I don't want you to tell anyone."

He said he wouldn't. I turned to go, and he said, "Uh, Heather, one other thing." I thought, "Is he going to ask me out?" Then, he said, "I kind of like your friend." I said, "That's cool. No big deal." I walked out. I was just mortified.

It's a fascinating story for so many reasons. One of them is this idea that you didn't really like this guy, yet you still wanted him to want you. So much of being a young woman is wanting to be desired.

It's messed up. I was the worst kind of girl that way. I just charted my value constantly. That's why, ultimately, the chapter is about friendship with women. And that's why female friendships at that time are so fraught. You're competing for limited resources, and the resources can barely complete a sentence in conversation with you.

I feel like girls in high school compete over guys not because they like the guy, but because they want to be the winner. It takes years to realize that the goal of the first date should not be to try to get the person to like you, but to decide if you like him or not. You're not paying attention to whether he actually makes you happy or delights you or whether you enjoy being around him. You're so focused on being the most beautiful, sparkly princess in the land. That's the curse. My daughter is 4, and it's happening right before my eyes. "Am I the most beautiful? Do I look beautiful?" And it's impossible. "Of course, honey. Why would you compare, honey?" It's hard to say the right thing every time. I hope that there has been progress since I was a kid, but I think there is something essential about our culture that scoops this little mermaid stuff down your throat. If I could emancipate my daughter from anything, it would be that compulsion to secure approval from creatures who are roughly as unsophisticated as garden slugs.

I identify so much with your frustration about being the comic relief as a girl, about not being "the pretty one." I instantly recognized myself in that. And how many of us must feel that way, because there really is only one pretty one, and she probably doesn't realize it.

There really only is one pretty one. That reminds me too. If there is one problem with the fairy tale it's the superlatives about looks. On the other hand, I always wanted the hottest guy. I could be blamed for the same kind of attitude. It's not like guys had the corner on that kind of judgment.

I remember the point where I stopped feeling like a night wasn't very successful if I wasn't the prettiest and the most charming girl at the party. It's so laughable to me now. You have a few kids, you get a little older. Even if you had the ability to aspire to that, it's like, "Who cares?" It's weird. It's like you're cursed with this compulsion to gain approval points from people.

Once you make the shift from trying to please men to trying to feel good about yourself, then everything changes. All the rest of the crap melts away. And that's when the possibility of having good relationships with women begins.

You realize women aren't really a threat, they won't take your princess crown.

It's so pathological. It feeds the way women get fixated on getting married too soon. There are so many bad things that fall from that one bad bit of culture.

I love the part toward the end of the book where you talk about the importance of telling the ugly truth about yourself to the people you date.

It just works much better. We try to sell guys a bill of goods about how cool we are, and how we can hang, and how easygoing we are -- especially if you have a history of being one of the guys. If you know how to impress guys in that kind of environment, you try to compulsively appeal to guys by seeming like someone who could sit on the couch for the next 50 years of your life doing bong hits and eating pizza and everything will be cool and you'll never talk about a single emotion that is flashing through you. But you're selling yourself short. Eventually, if you attract people that way, big surprise, those are the ones who don't like chicks who break down and cry unexpectedly. They act like you dropped a rock over their heads when you do that. The message you get is, "I'm a psycho 'cause I cry." It took me so long to realize, you know, crying: It's a human thing. There's absolutely nothing wrong with breaking down and crying, actually. It doesn't mean that you are dipped in shit when you cry. It's an opportunity to connect with someone.

Shares