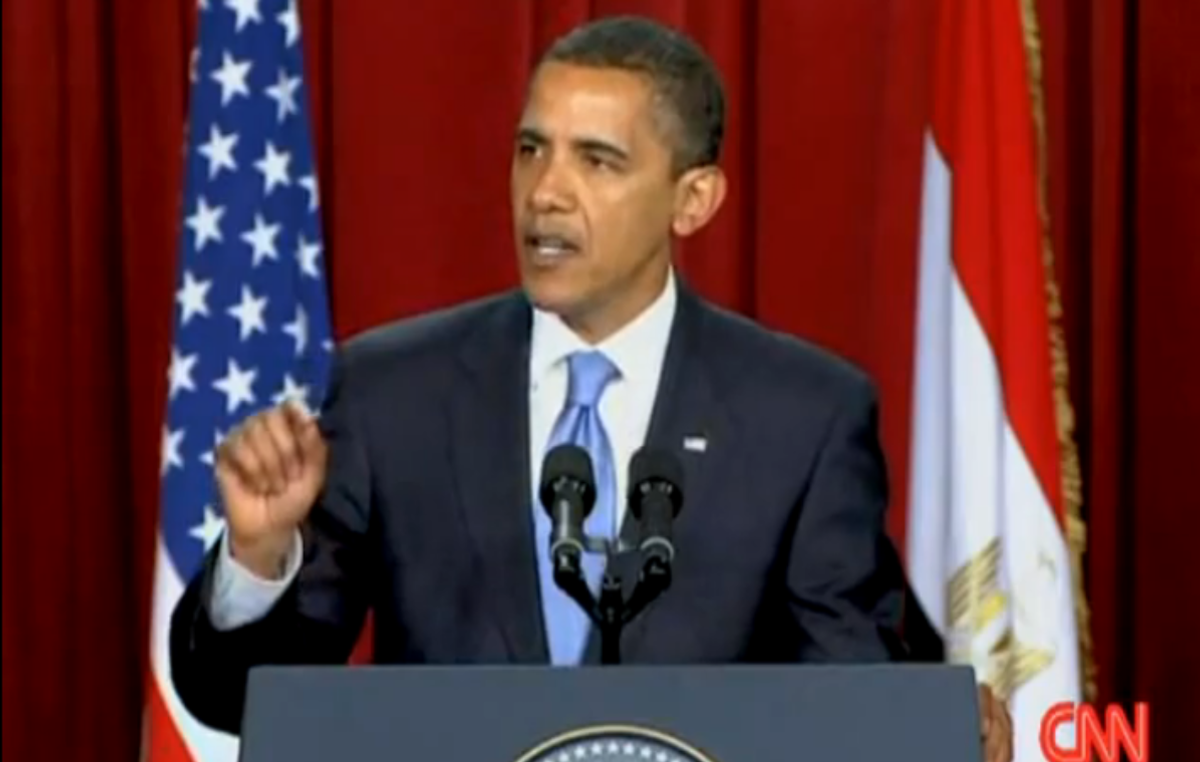

In his 2009 speech in Cairo, President Obama acknowledged that tensions between the Western and Muslim worlds have "been fed by colonialism that denied rights and opportunities to many Muslims, and a Cold War in which Muslim-majority countries were too often treated as proxies without regard to their own aspirations." He failed to mention that, long after the fall of the Berlin Wall, many of these countries were still being treated as proxies, their leaders -- including Hosni Mubarak -- propped up by the West. But his audience in Egypt and beyond hardly needed reminding.

In a bold new strategy, Obama called for an increase of democracy, openness and freedom across the Muslim world. Just weeks later, that strategy was put to the test for the first time when, in Iran, the Green movement took to the streets in protest at the so-called stolen election. As demonstrations were violently suppressed and international condemnation grew, Obama hesitated. If he came out strongly against the election results he would jeopardize future relations with President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. If he ignored the crisis, he risked being seen as weak. In the end, he chose a middle path, not congratulating Ahmadinejad and expressing "deep concern" at the legitimacy of the election and the treatment of protesters.

The dilemma Obama has faced over the past week has been very different. Egypt is not a long-term foe, but a key strategic ally. America relies on Egypt for access through the Suez Canal, for maintaining its 30-year peace treaty with Israel, for supporting the Middle East peace process and for cooperation against terrorism. Obama does not want to cut Mubarak adrift unless he absolutely has to as his demise would dramatically reconfigure power relations in the region. With oil prices edging toward $100 per barrel and the existence of a not insubstantial Islamist movement, the U.S. fears that the advent of democracy in Egypt might not be in America's strategic interests. As protesters enter their second week on the streets and international condemnation of Mubarak's regime increases, Obama is again prevaricating.

Despite America's concerns, if the people on the streets are successful in ousting the discredited Egyptian president a confluence of factors bode well for the introduction of a genuine and progressive form of Arab democracy in Egypt. Despite having lived under emergency laws for over 30 years, civil society movements there are strong and there are over 20 well-organized political parties. While there is some support for the Muslim Brotherhood, Egyptians do not want to create an Islamic state and 70 percent expressed concern at the rise of Islamic extremism in a 2010 poll by the Pew Research Center.

Egypt also has an exceptional potential leader in the shape of Mohamed ElBaradei, the Nobel laureate who commands respect at home and abroad and who could represent a unifying leader. Indeed ElBaradei’s call for a boycott of last December’s parliamentary elections not only brought many groups together but the boycott itself was the final nail in the coffin of Mubarak’s claim to legitimacy.

The emergence of a genuine non-aligned democracy in Egypt might give Western governments cause for anxiety, but rather than hedge their bets perhaps now is the time for Western leaders to recognize the tide of history and come out strongly in support of the Egyptian revolution. While the U.S. can't decide Egypt's future, withdrawing U.S. support for Mubarak would rapidly hasten his demise and enable Obama to live up to the commitments he made in the historic speech in Cairo that reverberated across the Muslim world.

Shares