In the early 1950s, my friend Marty Glaberman wrote a pamphlet called "Punching Out," reflecting on his experience of working in the auto factories of Detroit. Marty later became a professor of labor history at Wayne State University. But when you talked to him or read his writings, it was always clear that he'd gotten the better part of his education from his decades "on the line" -- participating in the constant struggle of workers to retain their humanity as they coped with the unrelenting pace of the assembly line. That was what he tried to convey in "Punching Out": the vitality of the working-class community that emerged on the shop floor. In Detroit's factories, people were creating not just cars, but a way of life.

When Marty died, 10 years ago, the city of Detroit was already in bad shape -- factories closing, people leaving, abandoned buildings going up in flames each Halloween in a grim festival of urban self-destruction. As it happens, Paul Clemens has given his new book "Punching Out" -- which follows the dismantling of a Detroit auto factory -- the same title as Marty's essay from six decades ago. Evidently this is a coincidence; there are no references in the text to suggest otherwise. But either way, the echo is meaningful, for Clemens is writing about the destruction of both a workplace and a social world.

The workplace in question was the Liberty Motors plant of the Budd Co. , one of the oldest factories serving Detroit's auto industry, opened in 1919. It stamped out the roofs, doors, tailgates and so forth that were then assembled into cars elsewhere. It changed hands in the 1970s and ended up as part of the German steel concern ThyssenKrupp. At its peak, 10,000 people were employed at the plant; by 2006, when it shut down, there were about 350 workers. A typical product of three decades of deindustrialization, then. As Clemens writes, the United States now has "more people dealing cards in casinos than running lathes, and almost three times as many security guards as machinists."

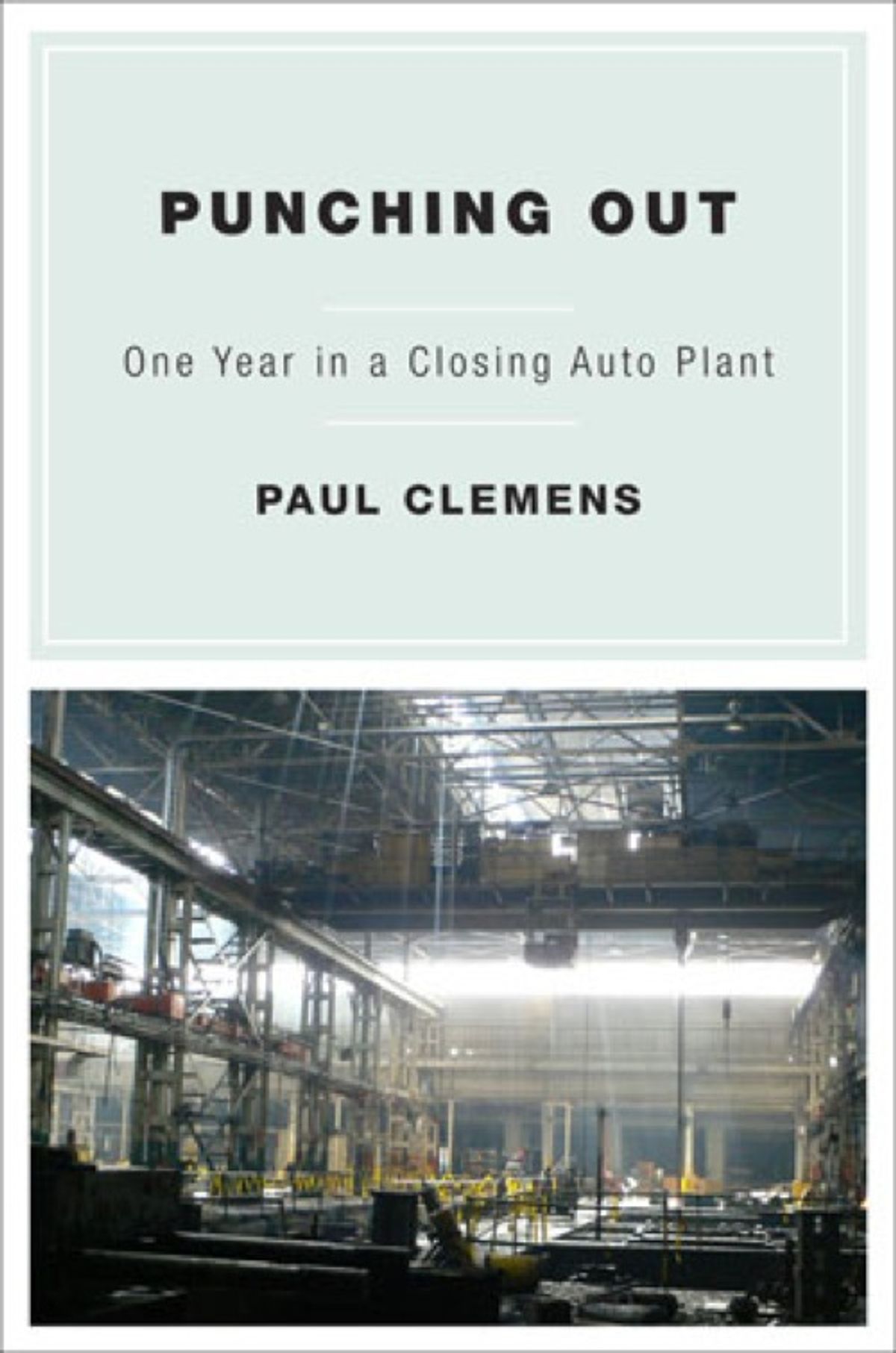

But "Punching Out" is not a retelling of the story of that decline. Instead, it is an account of what comes afterward -- when the workers have been let go, the security guards posted to keep property from being stolen or destroyed, and crews brought in to dismantle the machinery and send it elsewhere (in this case, to Mexico, where a new factory is opening). The author gained access to the inside of the plant -- wandering around its "eighty-six empty acres in the center of the city of Detroit" -- during the long months it took to break it down. The executives of the ThyssenKrupp corporation weren't helpful, but he became friendly with the guys doing the work, and his narrative is a blend of impressions from talking to them and what he could learn about the place from poking around in the ruins.

At times, "Punching Out" feels like a book in search of a thesis to pull it together, and Clemens admits as much. He is keen to avoid indulging in melancholy prose-poetry or cheap philosophizing about the "creative destruction" of postindustrial society. The real vigor of the book comes from its character sketches of the men who shrug off the label "vultures" as they go about their jobs.

In my friend Marty's day, the factories ran constantly. You'd "punch out" at the end of a shift, but somebody else was walking in. Clemens calls his book the story of "the American working class mopping up after itself." And then the lights go out. Nowadays what's open all the time is the casino, where nothing is made, and scarcely anyone leaves as a winner.

Editor's note: Marty Glaberman's essay "Punching Out" is collected in this volume.

Shares