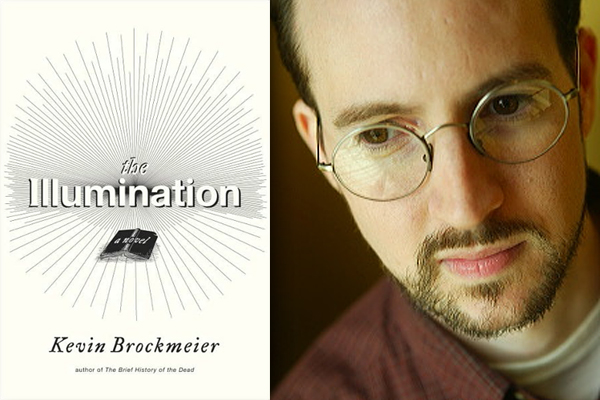

“The Illumination,” Kevin Brockmeier’s new novel, begins on a day when, all across the globe, people in pain begin to glow. “A hundred threads of light” twist down the muscles of a doctor’s stiff neck, and the cancerous lungs of an actor receiving a lifetime achievement award on TV shine through his tuxedo “like chandeliers.” Every manifestation of physical misery, from the brief firefly gleam of a pinch to the incandescence of leukemia, becomes visible.

I know, I know, this is a dangerously precious premise. And when I tell you that the linked stories of “The Illumination” are connected by a journal in which a woman has transcribed daily love notes received from her husband — a journal that, after the woman’s death, gets passed from one character to another — the novel will sound even more dubious. Both ideas seem like just the sort of phony magical realism cooked up by precocious Brooklyn novelists with little life experience and a yearning to appear soulful; tragedy in a snow globe: shake it up and watch it sparkle.

“The Illumination” is not, however, that kind of book. Not at all. This will be obvious to anyone who reads past the first few pages, or, for that matter, any page, chosen at random. The characters who momentarily possess the late Patricia Williford’s diary are too distinctive and idiosyncratic to be cute, and Brockmeier’s consistently arresting observations have the throb of lived — rather than merely imagined — experience. Take the passage in which a character calls an ambulance to take his terminally ill sister to the hospital and, following it in his car, can barely keep up with the speeding vehicle. Then, “abruptly and inexplicably, at the corner of Burlington and Court, the driver began obeying the traffic laws.”

That particular character, Ryan, is an evangelical missionary, a man who goes door to door handing out pamphlets, not because he believes, exactly, but because he’s not sure what else to do with himself after losing everyone he loves. “Nothing was so clear to him as that life presented a riddle to which no one knew the answer,” he decides, but his beloved sister had faith, and so he proselytizes for her sake, finding that “evangelism was a job like so many others.” The details of Ryan’s life — from the invalids and young mothers who slam their doors in his face during his daily suburban rounds to the out-of-town missions, staying in cheap hotels with “loamy” beds — is stitched so securely to the fabric of reality that he’s never in danger of devolving into a cliché or a symbol.

Brockmeier’s other focal characters include a misfit schoolboy who thinks he can perceive the distress of objects, a homeless bookseller, and a writer whose happiness has been ruined by inexplicably chronic canker sores that make it painful to speak, eat, smile or kiss. Each, like Ryan, materializes into a human being you can hardly bear to part from when his or her chapter ends. Each of those chapters tenderly configures itself to the person it depicts. Chuck — who has just turned 10 and abides by what seem like joyless compulsions to the adults around him — gets a chapter in which every sentence contains exactly 10 words: “He used all sixty-four crayons when it was coloring time. The trees he drew might be blue, black or yellow. It didn’t matter, as long as every color was happy.”

The rigid, seemingly arbitrary structures of Chuck’s life are suffused with a covert kindness, while Ryan, who appears to be an exemplary Christian, is only going through the motions. Nevertheless, as time goes by, in Burkina Faso and Tunisia and Sumatra and Detroit, his actions become less distinguishable from his intentions, and the prose in his chapter takes on the stately cadences of the scripture he never even mentions. Musing on “the Illumination” (as the strange new luminosity has been dubbed), he observes that it hasn’t, alas, led to greater compassion, and now a generation of children have grown up taking it for granted. “Still they grew into their destructiveness,” he thinks, “and still they learned whose hurt to assuage and whose to disregard, and still there were soldiers enough for all the armies of the world.”

“What if our pain was the most beautiful thing about us?” reads the unfortunate publisher’s blurb on the back cover of my copy of “The Illumination.” That suggestion is a sentimental obscenity — only someone unacquainted with real pain would ever imagine it beautiful. What the novel does consider is the meaning human beings find in our suffering; each of the character represents a different reaction to it. The canker-plagued writer allows it to isolate her. Chuck displaces his own hurts onto the everyday objects that are the only things he has the power to protect. Patricia Williford’s grieving widower forms an alliance with a self-cutting teenager.

And lonely Ryan contemplates theodicy, the conundrum of a cruel world created by a supposedly loving god. What good to humanity is God’s love, he asks himself, “fluttering like a bird around the margins of their wretchedness. It was a sad little robin of a word, His love. It fled at the first sign of cold weather. Its bones were hollow and filled with air. Anyone could see how feeble it was, how insubstantial. How wrong.”

Writing like that prevents Brockmeier’s novel from becoming merely bleak or lugubrious, a real hazard given his theme. Writing well about pain and grief, however, is never enough. In “The Illumination” it isn’t our agonies and discomforts that define us, but the selves we build in response to them. And so, over the course of each chapter, each character eventually eclipses whatever bad things have happened to him or her in the reader’s mind; their misfortunes become the least of who they are. Suffering isn’t beautiful or even meaningful, but it certainly does shine a light on what is.