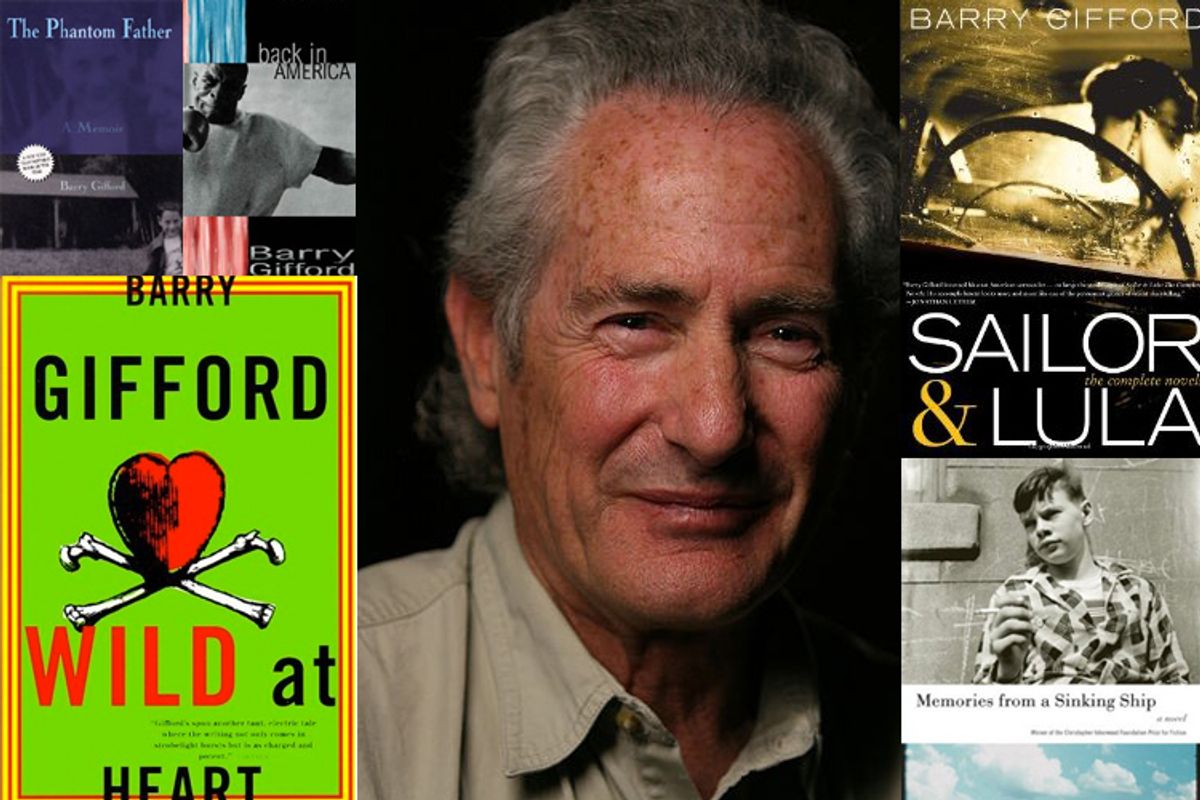

"It has taken Barry Gifford more than twenty years and nearly as many books to achieve a big reputation, and now that he finally has one, it's mostly wrong." So I wrote in Entertainment Weekly in 1990 when Gifford's novel "Wild at Heart" was made into a film by David Lynch, and Gifford was hailed by many critics as a master of new-wave crime fiction.

The image was reinforced by his work as the founder of Black Lizard Press in Berkeley, Calif., where he reprinted dozens of crime novels by 1950s drugstore book-rack legends such as Jim Thompson, David Goodis and Charles Willeford. More than two decades later, Gifford has succeeded in shedding the reputation of crime writer -- something he never aspired to in the first place -- without acquiring a new one.

Over the last 20 years, Gifford's output has doubled -- that is, if you count all seven of his "Sailor and Lula" novels as one volume (as they are in the recent edition from Seven Stories Press); his three plays, "The Hotel Room Trilogy," as one; and each of his 13 volumes of poetry separately. Gifford's vast and diverse body of work has frustrated critics by defying easy categorization. Among my fictional favorites in his oeuvre are "Port Tropique" (1980, reprinted in 2009), a stylish thriller that reveals Gifford's crime novel roots; "Landscape With Traveler" (1980, regrettably out of print), about a gay Naval officer, written in short, lyrical chapters that owe much to the influence of classical Japanese writers Sei Shonagon and Lady Murasaki; and "Wyoming" (2000, a Los Angeles Times novel of the year), a novel about a woman and her young son on a car trip through the South and West told entirely in dialogue.

What stands out most about these and other of Gifford's fictions is how original they are without in the least smacking of the experimental; mastering a subject and then moving on has been the story of Gifford's life. His enormous body of work reflects a lifetime of experience and influences. With Lawrence Lee, he is the co-writer of two biographies, "Saroyan: A Biography" (of William Saroyan, 1984) and "Jack's Book: An Oral Biography of Jack Kerouac" (1978). He is the author of "A Day at the Races: The Education of a Racetracker" (1988), a book about the delights of horse racing that would have brought a smile to the face of A.J. Liebling; "The Neighborhood of Baseball: A Personal History of the Chicago Cubs" (1981, about the joys and many woes of growing up near Wrigley Field); and "Out of the Past: Adventures in Film Noir" (2001, and currently available from the University Press of Mississippi).

The latter is Gifford's homage to his favorite heroes and heroines from the world of dark cinema. The book has earned him a large cult following from readers only vaguely aware of Gifford's fiction and biography. Sample from the entry on "Devil Thumbs a Ride," a grimy 1947 crime film starring Lawrence Tierney: "I got up at 3:30 in the morning to watch this movie on TV -- the perfect time for it." On Tierney: "There is no daylight in that face." On "The Asphalt Jungle": "Jungle reflects two shades, dark and darker."

Perhaps the best book for checking into Gifford's neon-noir lit sensibility is "The Cavalry Charges: Writings on Books, Film and Music" (2007), a collection of essays dedicated to his friend Matt Dillon, for whom he wrote the screenplay for "City of Ghosts," the 2003 film that Dillon directed. Gifford indulges in reveries on favorite TV shows, including "City Confidential," the A&E true crime series that ran from 1998-2005; musicians such as Artie Shaw; and writers whose work made an impression on his own sensibility, ranging from B. Traven, the mysterious author of "The Treasure of the Sierra Madre," and, most unlikely of all, Clair Bee, author of the Chip Hilton novels for boys written between 1948 and 1965 in which the hero, Chip, leads his teammates to success by conveying the virtues of self sacrifice, discipline and honesty.

"I imagine," writes Gifford, "that I must have learned something from reading these books, and that I'm probably still operating according to some of the same principles and under those same delusions." No easy task for the son of a small-time Chicago racketeer. He recalled his childhood in 1992 in "A Good Man to Know," subtitled "A Semi-Documentary Fictional Memoir." (The book is out of print, but Gifford incorporated much of the material into the 2009 novel "Memories From a Sinking Ship.") The point of view of his long-suffering mother was covered in a 1984 novel, "An Unforgettable Woman."

Gifford spent his early years working at a variety of jobs, from merchant seaman to rock musician. He attended the University of Missouri on a baseball scholarship but found the environment a little stuffy. "I didn't have any friends," he told me, "except for the six beatniks on campus, and two of them were from New York." After a year at Missouri he hit the road for Manhattan and kept going all the way to London, where he enrolled at Cambridge on a non-degree basis. The few months he spent there were enjoyable but proved to him once and for all that "I'd never be a scholar."

Once, when I asked Gifford about whether an incident he wrote about was part of his personal experience or invented, he shrugged and answered, "You spend a lot of time observing life, then you make things up."

In interviews and profiles over the years, Gifford has often engaged in myth mongering, sometimes being deliberately fuzzy as to whether material in his books is autobiographical or fictional. "Barry likes the tough guy image," says Michael Swindle, a New Orleans-based poet/writer. "He used to drive around Berkeley in his 'pimpmobile'" -- a white 1975 Cadillac Eldorado -- "but that was just for show. It was sort of like he was the Rick Blaine of novelists -- you know, the character with a mysterious past Bogart played in 'Casablanca.' That's kind of what he is, the Bogart of novelists."

Swindle cautions that "You've got to be careful around him. You might wind up in one of his books." Swindle found that out a year after a car trip with Gifford across the Southern states, when he opened a copy of "Sailor's Holiday," one of the Sailor and Lula novels, and found a character named Mississippi Mike Swindle.

The Sailor and Lula novels have proven to be Gifford's most popular works, and not just because of the film starring Nicolas Cage and Laura Dern, which was not a box office success. ("Wild at Heart," which takes its title from Tennessee Williams, is a much better book than Lynch's film is a movie. Many aficionados of both men's work prefer Lynch's film "Lost Highway," from Gifford's screenplay, and "Perdita Durango," Gifford's second Sailor and Lula novel made into a film by Spanish director Álex de la Iglesia in 1997.)

The characters Sailor Ripley -- Sailor's name was a tribute to a free-spirited poet Gifford drank sake with on a visit to Japan -- and Lula Pace Fortune were inspired by people he observed in a hotel in Southport, N.C., where he overheard part of a conversation going on in the next room. His notes became the genesis of a road novel, "Wild at Heart," about two young people fleeing across the South. Sailor and Lula's story is told largely in a combination of dialogue and inner monologue; not the undernourished patter of most thrillers but an unsettling torch blast of language that uses the characters' inarticulateness to express their yearnings. Through seven novels, most of them set on the roads of the American South, life reveals itself pretty much to be what Lula thought in the first book, "The world is wild at heart and weird on top."

By the final book, "The Imagination of the Heart," Lula, now 80 and living in the wasteland of post-Katrina New Orleans, tells us, "I am ready for an answer why theres [sic] endless madness and suffering on the planet. All I know is everything's been out of control from the beginning."

Taken together, the Sailor and Lula stories form one of the most amazing love tales in American literature, one that continues to evolve even after Sailor's death. (In true rock-star fashion, he flames out in a car wreck.) Like a trailer-park Tristan and Isolde, their love survives all obstacles -- including car chases, holdups, drug deals gone wrong, Satanic parents, sociopath enemies, and even a lengthy prison stretch for Sailor.

The novels take place in towns with such names as Big Tuna, Texas; Divine Water, Okla.; Candido Aguilar, Mexico; and even the Pee Dee River Correctional Facility, involving characters with names like O-Boy Wilson, Perdita Durango, Pea Ridge Day, Consuelo Whynot and Coot Veal. (The last, I happen to know, is stolen from a light-hitting shortstop who spent six years in the majors from 1958 through 1963.) As I wrote for the Los Angeles Times in a piece about Gifford's story collection "Night People," "The characters in 'Night People,' like those in 'Wild at Heart' and Gifford's other Sailor and Lula stories, seem like the kinds of people you glimpsed once briefly when you were stuck in a bus station late at night in a small town or on a subway train when it was stalled and let you off in a part of town you'd never seen before." I might have added, or when your tire blew and left you stranded in a border town.

Gifford writes about men and women of whom you ask, "Where do they go during the day?" And the answer is that they are the kind of people who always seem to show up after dark because they carry their own private night with them. You'll be glad that you went along for the ride, but also glad that you have a kinder, saner world to return to.

Shares