Not since World War II has the federal budget deficit made up such a big chunk of the U.S. economy. And within two or three years, economists fear the result could be sharply higher interest rates that would slow economic growth.

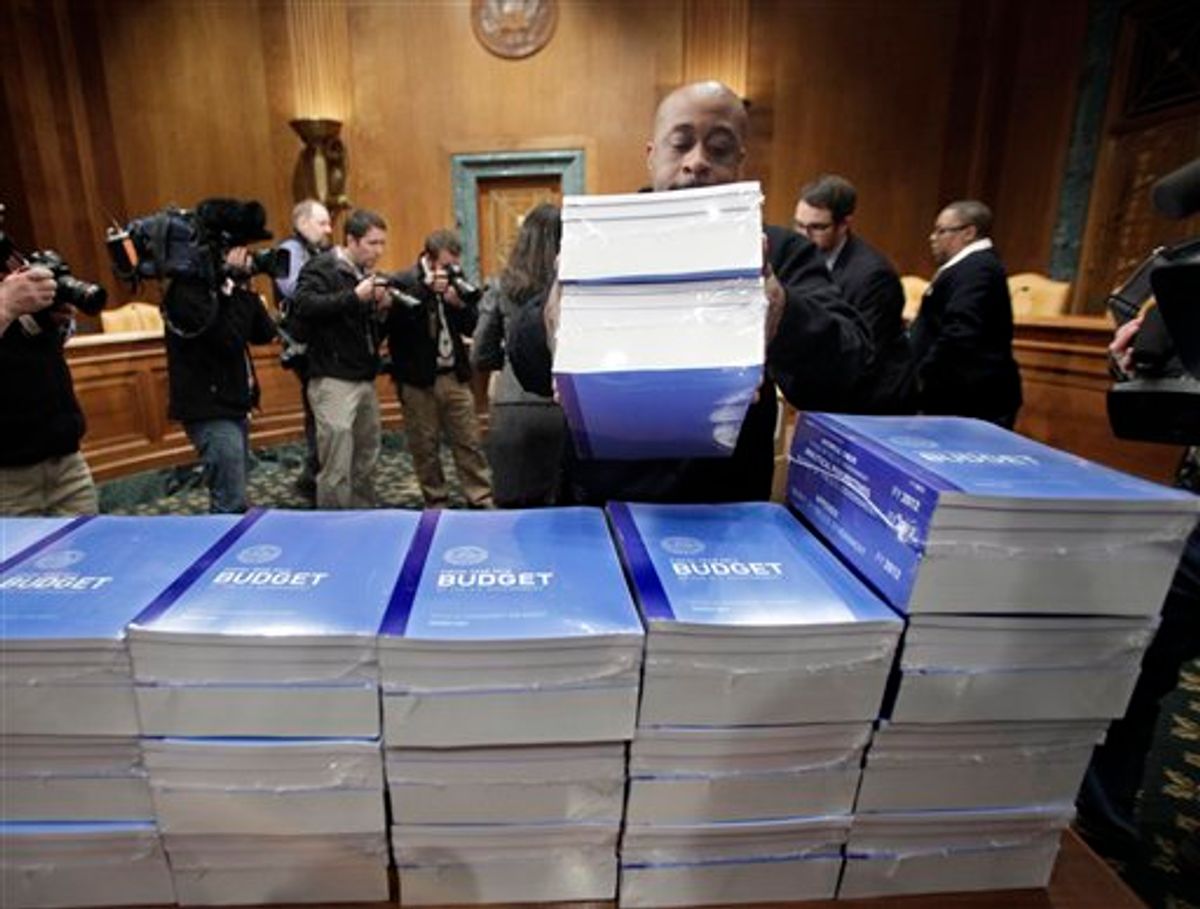

The budget plan President Barack Obama sent Congress on Monday foresees a record deficit of $1.65 trillion this year. That would be just under 11 percent of the $14 trillion economy -- the largest proportion since 1945, when wartime spending swelled the deficit to 21.5 percent of U.S. gross domestic product.

The danger is that a persistently large gap in the budget could threaten the economy. Investors would see lending their money to the U.S. as riskier. So they'd demand higher returns to do it. Or they'd simply put their cash elsewhere. Interest rates on mortgages and other debt would rise as a result.

And if borrowing turned more expensive, people and businesses might scale back their spending. That would weaken an economy still struggling to lower unemployment, revive real estate prices and restore corporate and consumer confidence.

So far, it hasn't happened. It's still cheap for the government to borrow money and finance deficits. But economists fear the domino effect if all that changes.

"The moment when markets react negatively to our budget deficit cannot be known in advance, but we are absolutely in the danger zone," says Marvin Goodfriend, an economics professor at Carnegie Mellon University's Tepper School of Business.

Higher interest rates would also raise interest payments on the federal debt. It would be costlier for the government to finance its operations. The interest payments themselves could then make the deficit increase, creating a vicious cycle.

Under the projections in Obama's budget, the deficit as a share of the overall economy would narrow from 10.9 percent this year to 7 percent next year and eventually to 2.9 percent by the 2018 fiscal year.

But after that, in the remaining years of this decade, the deficit would widen slightly as a percentage of the economy. It would average about 3.1 percent because of escalating costs for programs like Social Security and Medicare as baby boomers age and receive benefits.

Economists generally say cutting the deficit to about 3 percent or less of the economy would be healthy. Deficits at that level are considered "sustainable" -- meaning they could be easily financed and wouldn't make investors nervous about the government's finances.

Most economists don't think the deficit should be cut deeply now. They say the economy remains so fragile -- unemployment is at 9 percent -- that it needs big government spending to invigorate growth.

In this camp is Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke. He's argued that now isn't the time to slash government spending or raise taxes. Instead, Bernanke has urged Congress and the White House to preserve federal stimulus -- including tax cuts -- in the short run but draft a plan to reduce the deficit over the long run.

A presidential commission last year made recommendations that Bernanke and other economists say could help curb the deficit over the long term. Its suggestions included raising the Social Security retirement age and reducing future increases in benefits. It also proposed increasing the gasoline tax and eliminating or scaling back tax breaks, like the mortgage interest deduction claimed by many Americans.

Obama embraced none of these proposals in his budget. But his plan is designed to cut $1.1 trillion from the deficit over the next decade, two-thirds of it from spending cuts. The rest would come from tax increases, such as limiting the deductions for high-income taxpayers.

In Bernanke's view, a long-term plan to reduce future deficits would mean lower long-term interest rates and increased consumer and business confidence.

For months, though, longer-term rates have been creeping up, driven by prospects of stronger growth and concerns about higher inflation. The yield on the 10-year Treasury note is now 3.61 percent. That's up sharply from 2.48 percent in early November.

That increase is making other loans, including mortgages, more expensive. The average rate for a 30-year fixed mortgage just rose above 5 percent for the first time since April.

Rates are still extremely low by historical standards. In 1983, during Ronald Reagan's first presidential term, the deficit soared to $208 billion, about 6 percent of the economy at the time. The rate on the 10-year note topped 10 percent. And getting a 30-year mortgage meant paying 13 percent.

Economists say that if investors trust that Congress and the White House will curb budget deficits over the long haul, interest rates could stabilize -- even if deficits exceed $1 trillion over the next year or two. But if investors lose confidence that Washington policymakers can curb the deficits, rates could rise sharply.

"It's all about perception," says Lou Crandall, chief economist at Wrightson ICAP, a research firm.

So far, China, the biggest buyer of U.S. debt, and other countries have maintained their appetites for Treasurys. Foreign demand for Treasury debt has helped keep U.S. interest rates historically low.

The reason is that the United States is still considered a haven for many foreign investors. That point was underscored by Europe's debt crisis last year, when money poured into dollar-denominated Treasurys.

If the United States had to finance its debt through U.S. investors alone, the government, along with American companies and consumers, would have to pay higher rates.

Last year's budget deficit totaled $1.3 trillion. That was just under 9 percent of U.S. economic activity. The first time the deficit topped $1 trillion was in 2009.

The growth of U.S. budget deficits has reflected the costs of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the continuation of broad tax cuts, the worst recession since the 1930s and a surge in spending on Social Security, Medicare and the military. The recession prompted higher government spending to stimulate the economy and cushion the effects of the downturn. It also reduced tax revenue.

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development estimates that the United States' deficit as a share of the U.S. economy will be smaller -- around 8.8 percent-- than the president's budget estimates.

Still, that would be a higher figure than for other major industrialized countries. The OECD projects, for example, that Britain's deficit this year will be about 8.1 percent of its economy. Germany's deficit is expected to make up 2.9 percent of its economy, Japan's 7.5 percent.

"So far, investors haven't been bothered by large U.S. budget deficits," says Jim O'Sullivan, economist at MF Global, an investment firm. "The fear is that could suddenly change. It's not clear whether investors will remain patient once the U.S. recovery is on track."

Shares