To warp Tolstoy's famous line: "Sane families are all alike; every crazy family is crazy in its own way."

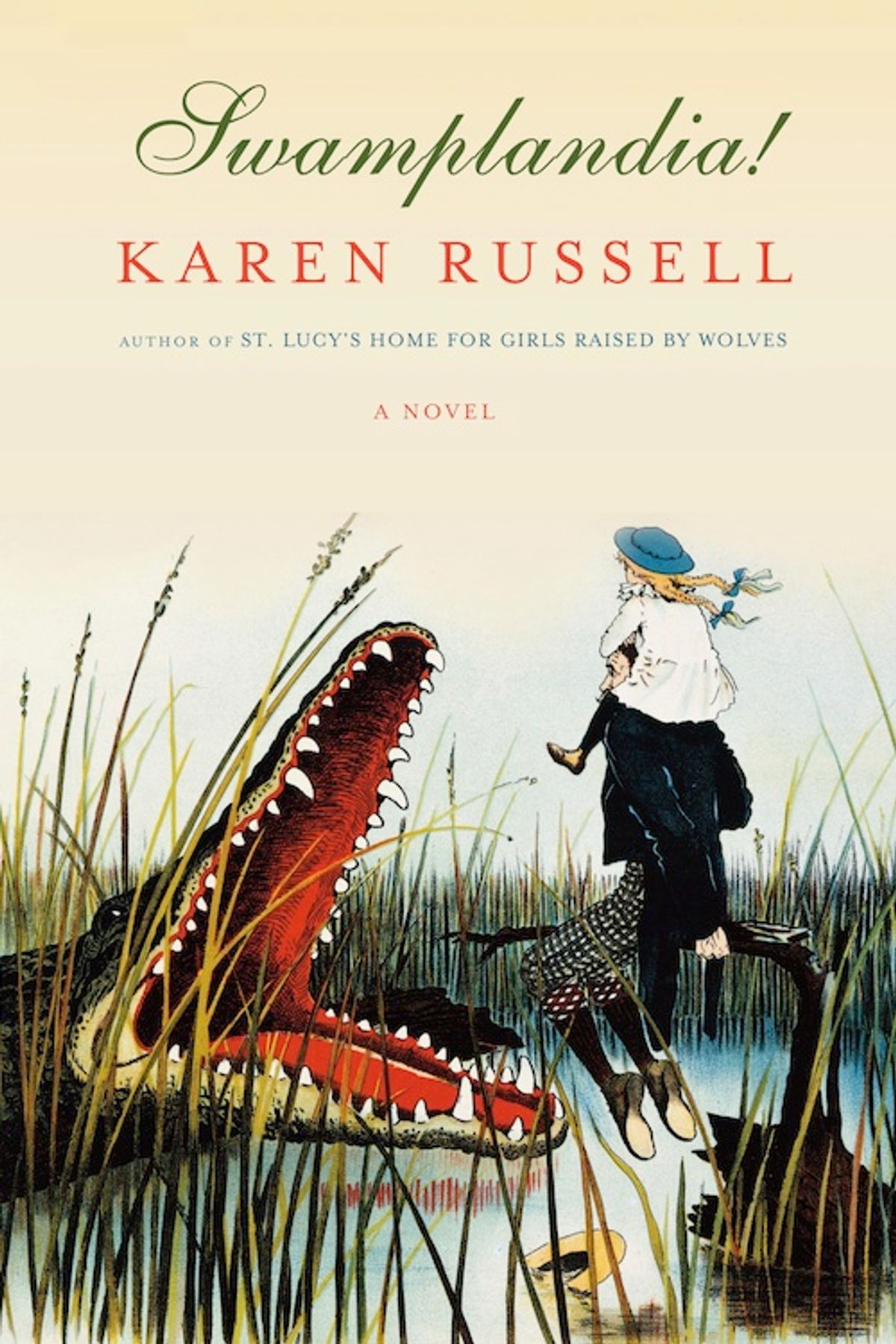

The literary trope of a tightly bound family or pseudo-family of grotesque, outré and outcast individuals operating as performers, or denizens of some cloistered Gothic environment, who serve in their eccentric manner as a symbolic commentary on society at large, has a long and prestigious lineage. Today the tradition is handsomely capped by Karen Russell's gonzo debut novel, "Swamplandia!"

We might peg the first truly modern such instance to Tod Browning's 1932 film "Freaks", with its cast of pinheads, little people and amputees, all allied against the "normal" world. Three years later Charles Finney's "The Circus of Dr. Lao" introduced the supernatural elements that often appear in subsequent treatments of the theme. Our next landmark, from 1946,William Lindsay Gresham's "Nightmare Alley," proved that a trashcan mimesis was quite sufficient to produce free-floating weirdness. This same era saw the uncanny flourishing, in their original "New Yorker" cartoon form, of "The Addams Family." A decade later, Robert Bloch's "Psycho," from 1959, offered the most stripped-down version of the crazed nuclear family, a one-member (or is it a two-member?) clan, whose motel is after all an entertainment facility of sorts.

We might peg the first truly modern such instance to Tod Browning's 1932 film "Freaks", with its cast of pinheads, little people and amputees, all allied against the "normal" world. Three years later Charles Finney's "The Circus of Dr. Lao" introduced the supernatural elements that often appear in subsequent treatments of the theme. Our next landmark, from 1946,William Lindsay Gresham's "Nightmare Alley," proved that a trashcan mimesis was quite sufficient to produce free-floating weirdness. This same era saw the uncanny flourishing, in their original "New Yorker" cartoon form, of "The Addams Family." A decade later, Robert Bloch's "Psycho," from 1959, offered the most stripped-down version of the crazed nuclear family, a one-member (or is it a two-member?) clan, whose motel is after all an entertainment facility of sorts.

Inspired by Addams, Ray Bradbury delivered his own tales of the similar Elliott family, starting with 1946's "The Homecoming," and pursued the pure circus form of the theme in his 1962 novel "Something Wicked This Way Comes." Coincidentally that same year, Shirley Jackson reasserted the creepiness of twisted and demented naturalism with "We Have Always Lived in the Castle." From that definitive milestone, it was a fairly long leap to Ian McEwan's 1978 upping of the ante with "The Cement Garden" and a comparable stretch before Carolyn Chute's "The Beans of Egypt, Maine" in 1985 and Katherine Dunn's "Geek Love" in 1989.

Perhaps discouraged by the hefty and exhaustive accomplishments of this majestic honor roll, authors have not ventured into this territory recently in great numbers. But two major admirable exceptions exist: the 1997 novel "Dogland" by Will Shetterly, in which the narrator recounts his adolescent years helping to run a Florida roadside tourist attraction dedicated to exhibiting every dog breed in creation; and Jeffrey Ford's 2008 book, "The Shadow Year," where a set of off-kilter siblings must deal not only with parental ineptitude but also murderous supernatural intrusions into their Bradburyesque town.

Sharing this noble literary bloodline of familial battiness, Karen Russell's exotic Bigtree clan comes out at the top of the weirdo heap. They operate a shabby gator-wrestling establishment on an island mired in Florida's swampy backwaters -- carnies of a sort, united against rubes and "mainlander" types. The paterfamilias, Chief Bigtree, has his heart and soul sunk into the ancestral place, as did his late wife, Hilola. (Her spectral presence, more imagined than real, haunts the characters and the book.) The teenage children, naturally, exhibit mixed feelings about their quirky destiny. Older daughter Ossie is a dreamy type, frustrated enough in her budding carnality to fall in love with ghosts. Son Kiwi is all naive practicality and has a desire to engage with the larger world. And youngest daughter Ava -- well, she's the most complex one of them all, befitting her status as our lush-voiced narrator, layering her adult sensibilities and vocabulary over this account of a few pivotal months in the history of Swamplandia! (the exclamation point is an inextricable element of their attraction's name).

Russell's zany density of setting, action and characterization had obviously been steeping for some time. In 2006, she appeared in "Zoetrope All-Story" magazine. (The tale now serves as a kind of alternate history to the events of the novel.) This story prominently opened Russell's collection, "St. Lucy's Home for Girls Raised by Wolves." Two other pieces -- "Lady Yeti and the Palace of Artificial Snows" and "Out to Sea" -- also figured at least tangentially in the Bigtree mythos. Overall, the wild-eyed fables here gleefully illustrate youthful strainings against the limits of society and consensus normality. At times Russell's work echoes that of George Saunders, though with a brighter, less mordant affect. (In fact, Saunders gets a shout-out on the acknowledgment page.)

Russell is no miniaturist or minimalist, but rather the opposite, heir to a Southern tradition of tall tales, thick descriptions, deep backstories and contrary cusses as anti-heroes. (Think of "A Confederacy of Dunces" as the template for such outrageous saintly fools.) Her theme of the onerous weight of a family's destiny would not be out of place in any Faulkner production. Neither is she shy about heaping on the plot. By the end of Chapter One, we've already been introduced to all the family dynamics and much of its history, and seen the threat on the horizon, which is a rival amusement park on the mainland called the "World of Darkness."

After grounding us brilliantly and intimately in the geography of the place known as Swamplandia! -- both its contemporary physical and psychological terrain, nuanced with some fascinating Florida history -- Russell makes the brave move of fragmenting the gestalt. Ossie and Kiwi run away separately, the Chief goes missing, and Ava is left alone on the island. Then arrives a mysterious figure, the Bird Man, who Ava is convinced can help track down her specter-misled sister, and the pair set off on a creepy odyssey whose mythic elements recall such larger-than-life quests as the tale of Orpheus and Eurydice, Frodo's wanderings and Conrad's "Heart of Darkness."

Meanwhile, half the narrative is now concerned with Kiwi's misadventures on the mainland while working at World of Darkness. This portion of the book, while highly amusing in a satirical manner that rags on many modern absurdities, lacks the epic and feverish derangement of Ava's adventures -- although, to be fair, Russell unites the two strands at the end very satisfactorily.

By expelling the characters from the safety of their shell, their self-constructed refuge or paradise or Eden, however shabby, Russell calls to mind another classic novel of familial insanity in a Gothic setting: Mervyn Peake's "Gormenghast" trilogy. Her expulsion of Ava and Kiwi into the "real world" has much the same force and flavor as the final volume in Peake's cycle, "Titus Alone."

Russell privileges a kind of idioglossia, the special language and set of associations known only to the Bigtree clan, fabulators all. (The very American trait of creating one's own identity is an explicit riff in the book as well.) For instance, the Bigtrees dub all gators "Seth," resulting in quite a few surreal sentences, such as: "A tiny, fiery Seth. Her skull was the exact shape and shining hue of a large halved strawberry." Ava's juicy, poetic voice, assembled through sheer willpower and joie de vivre and desperation from a self-taught young genius's love of language, is what carries this book even more so than the bizarre events. Without rendering Ava as some sort of impossible freak, Russell nonetheless employs subtle craft to highlight her uniqueness born of isolation and dreaminess. In a way, Ava is kin to the "girls raised by wolves" from the title story in Russell's collection.

If you were to take the exuberantly fecund tropical paintings of Martin Johnson Heade and commission the ghost of Angela Carter to write a story based on them, you might very well end up with something approaching the garish and fierce beauty of "Swamplandia!"

Shares