When Andre Dubus III was 14, the older brother of a neighborhood girl stormed over to his family's row house in an old mill town in Massachusetts. Dubus' 13-year-old brother, Jeb, had been fooling around with the girl, and now her brother, on leave from the Army, intended to punish him for the presumption. What happened next became totemic in Dubus' memory: The beefy M.P. punched Jeb twice, and when the boys' mother came out of house to chase him away, he called her a whore. Dubus himself stood transfixed, "my feet were bolted to the concrete, my arms just tubes of air, my heart pounding somewhere high over my head."

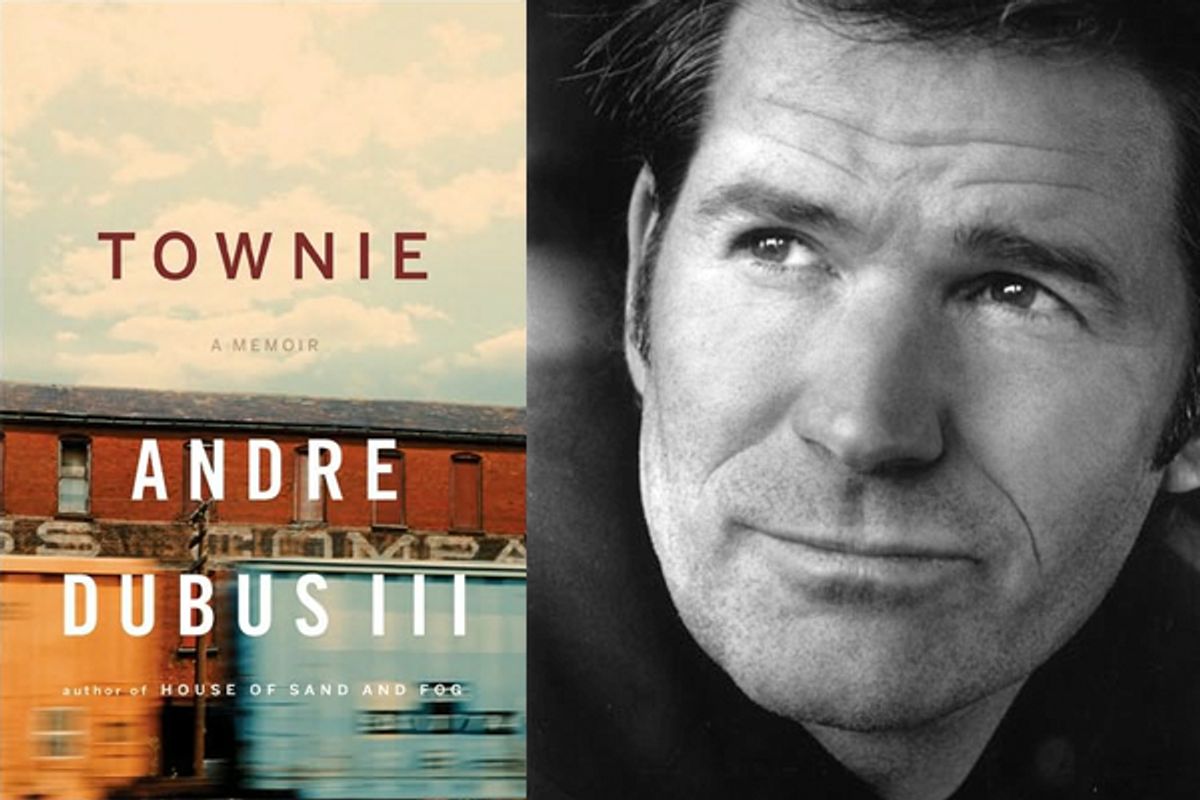

Such incidents weren't unusual, not in the Avenues, the neighborhood Dubus -- a novelist best-known for "The House of Sand and Fog" -- describes in his new memoir, "Townie." It was a domain of swaggering bullies and weak, negligent or absent authority figures. A few years earlier, yet another thuggish neighbor had stolen the brand-new bicycles given to Dubus and his three siblings, then brazenly rode one of them down the middle of the street, looking right through Dubus as if he weren't even there. Seeing Jeb beaten up by a grown man made Dubus feel even more helpless and cowardly, so from that day forward he began lifting weights, resolving to "get so big I scared people, bad people, people who could hurt you."

"Townie" recounts Dubus' sojourn in the kingdom of violence, and its counterpoint, the time he spent with his father, Andre Dubus II, an acclaimed author of austerely beautiful short stories about the anguish of working-class life. Dubus' parents split up when he was 10, leaving his mother to raise four kids on a social worker's salary, supplemented by what little alimony her ex-husband could eke from his job teaching creative writing at a nearby college. She and her children lived in the Avenues because they were poor, and while Dubus' father was close to broke himself, he nevertheless inhabited the tranquil "green world" of the campus, spending his days writing and jogging and his nights drinking with friends and dallying with rich, pretty students.

Meanwhile, Dubus' sister fell for one loser after another, some of them abusive, and for a while she sold drugs out of the house while their mother was at work during the day. Jeb was a creative oddball who played classical guitar, once wore a tail from a dead cat as a tie and had a long-term affair with his 35-year-old art teacher. There was never quite enough food, and their mother was always exhausted. The household slipped into disorder and decay; Dubus once got up in the morning to find that a gas burner on the stove has been left on all night. Worst of all were the frightening, loutish boys and men on the streets, at school and, all too often, in his own home.

The muscles Dubus built and the boxing he soon took up seemed absolutely necessary to his survival. Yet learning how to fight -- a matter, as he saw it, of breeching a "membrane" surrounding not only his opponent's face and body, but his own -- mangled his insides. Working himself up into a state in which he didn't care if he hurt another human being, in which he wanted nothing more than to do just that, gave him a "dark, tilting feeling I had added something to myself that each time I used it subtracted more than it gave."

This is a memoir both disconcertingly naked and immensely careful; Dubus refrains from bitterness the way a Buddhist monk renounces worldly possessions. He loved and admired his father, even though he could not help resenting him for abandoning their family to the tender mercies of the Avenues. The writer and teacher who was so good at drawing people out, who sought and absorbed their stories so eagerly, never seems to have understood how deprived his own children were, not merely financially but culturally and socially, as well. He was amazed to learn that his teenage son knew nothing about baseball (who would have taught him?) and had never heard of Manhattan. When Dubus enrolled in the college where his father taught, he overhead some girls in the cafeteria marveling that he was their teacher's son: "Look at him. He's such a townie."

Dubus' circumspection makes the pain of such moments even more biting. It's tempting to get angry on the author's behalf, but "Townie" patiently teaches its readers that rage is self-poisoning. Besides, there's a thinness to memoirs of recrimination that makes them ultimately unsatisfying; they're didactic rather than artful.

Here, by contrast, there is art in abundance, in the way, for example, that Dubus' descriptions of his run-down neighborhood gradually change as the narrative goes along. In the early chapters, it's all weedy yards, broken sidewalks and the sound of "the canned laughter and commercial jingles of six or seven TVs" drifting from open windows in the summer -- the sensory impressions of a child, who is, like most kids, a pedestrian. Later, the teenage Dubus sees his town as a collection of buildings with stories attached to them, like "Saldana's bakery that'd been closed down because the owner hired only Puerto Ricans and Dominicans straight from their homeland and was accused of never paying them."

For Dubus, salvation lay in getting at the stories imprisoned within a reality that at first seemed merely brutal and mindless. "Townie," in addition to probing the wounds of class and family, explains how the son became, like his father, a writer. If that narrative is the least remarkable aspect of this book, it's nevertheless intimately entangled with Dubus' quest to understand his father and to escape the lure of violence. Long before the end of "Townie" it becomes evident that Dubus reached a maturity his father never quite attained. His growing up may have been hard, but he grew up all the way.

Shares