The standoff between Pakistan and the United States over the detention of an American CIA contractor held in the fatal shooting of two Pakistanis is posing a growing diplomatic quandary for both countries.

Some members of Congress, Democrats and Republicans alike, are threatening to cut off funds to Pakistan if Raymond Allen Davis is kept much longer in a Pakistani jail. But turning him over to the U.S. could unleash a torrent of anti-American sentiment across Pakistan, threatening to undercut that country's fragile civilian government.

With anti-government protests sweeping the Middle East, public restlessness and anger could ripple as far as Pakistan, probably making the timing less than ideal for a government in an Islamic country to make a public show of cooperation with the United States.

The U.S. maintains that Davis, 36, is exempt from criminal prosecution under the principle of diplomatic immunity and should be turned over to American authorities. The U.S. also claims Davis acted in self-defense when he shot the two men he says tried to rob him.

Does the U.S. still maintain that position despite the disclosures that Davis was working as a CIA security contractor? "Yes," insisted State Department spokesman P.J. Crowley on Tuesday.

Crowley said U.S. Ambassador Cameron Munter met Tuesday in Pakistan with that country's foreign affairs minister, "continuing our work with Pakistani authorities to resolve the issue."

But no easy face-saving resolution for either side appeared in sight.

Pakistan's government thus far has not offered a formal position on the issue of diplomatic immunity, despite efforts to try to ease tensions by Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman John Kerry, D-Mass., who visited Pakistan last week at the request of President Barack Obama.

A judge last week put off ruling on the case until mid-March to give the government more time to formulate an official position.

Kerry later said that there were still "very difficult issues" surrounding Davis' legal situation but that several options remained. The senator expressed hope that things will be worked out.

If the dispute continues to fester, it could set back gains the U.S. has claimed in rebuilding trust for Pakistan's military and in winning that country's cooperation in going after al-Qaida and other militants inside the country. The standoff could also threaten billions in U.S. aid.

Also hovering in the background: the security of Pakistan's nuclear arsenal, given the apparent lack of influence of the fledgling central government.

The controversy is the latest in a series of recent setbacks in U.S-Pakistani relations and underscores growing friction between the CIA and its Pakistani counterpart, the Inter-Services Intelligence directorate, commonly known as ISI.

"It certainly complicates relations between the U.S. and Pakistan," said Mark Quarterman, a senior adviser at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington think tank. "This is an issue that has dominated the headlines and political discourse in Pakistan since the shootings."

In particular, U.S. drone strikes inside Pakistan, which have claimed civilian casualties, are "very unpopular among the Pakistani people," who generally think the government has already acquiesced too much in cooperating with the U.S., he said.

"A relationship that has been strained at times anyway was just sent into a tailspin by the Raymond Davis incident," said Quarterman, who headed a United Nations technical team that helped investigate the assassination of former Pakistani Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto.

Analysts in both the United States and Pakistan said that the ruling Pakistan People's Party is weak to begin with and that the shooting raises new questions about its ties to Washington and its very stability.

It has only been three years since the party's electoral victories restored civilian democracy after nearly a decade of military rule, and the government is still struggling to get its footing.

"On the one hand, the government wants to please the Americans and bow down to their wishes," said Talat Masood, a Pakistani political and military expert. "On the other hand, it wants to tell the Pakistani people it is not giving in to U.S. pressure."

Previously, the administration had identified Davis as simply "a diplomat." U.S. officials have said he was in Pakistan on a diplomatic passport.

The Associated Press and several other news organizations learned about Davis working for the CIA last month, immediately after the shootings, but withheld publication of the information because it could endanger his life while he was jailed overseas.

The AP had intended to report Davis' CIA employment after he was out of harm's way, but the story was broken Sunday by The Guardian newspaper of London.

He was working as a CIA security contractor -- essentially a bodyguard -- and living in a safe house in Lahore, according to former and current U.S. officials who spoke on the condition of anonymity because they weren't authorized to talk publicly about the incident.

There are hundreds of CIA employees on the ground in Pakistan, which is one of the agency's biggest stations. Davis' arrest raised concerns about their safety.

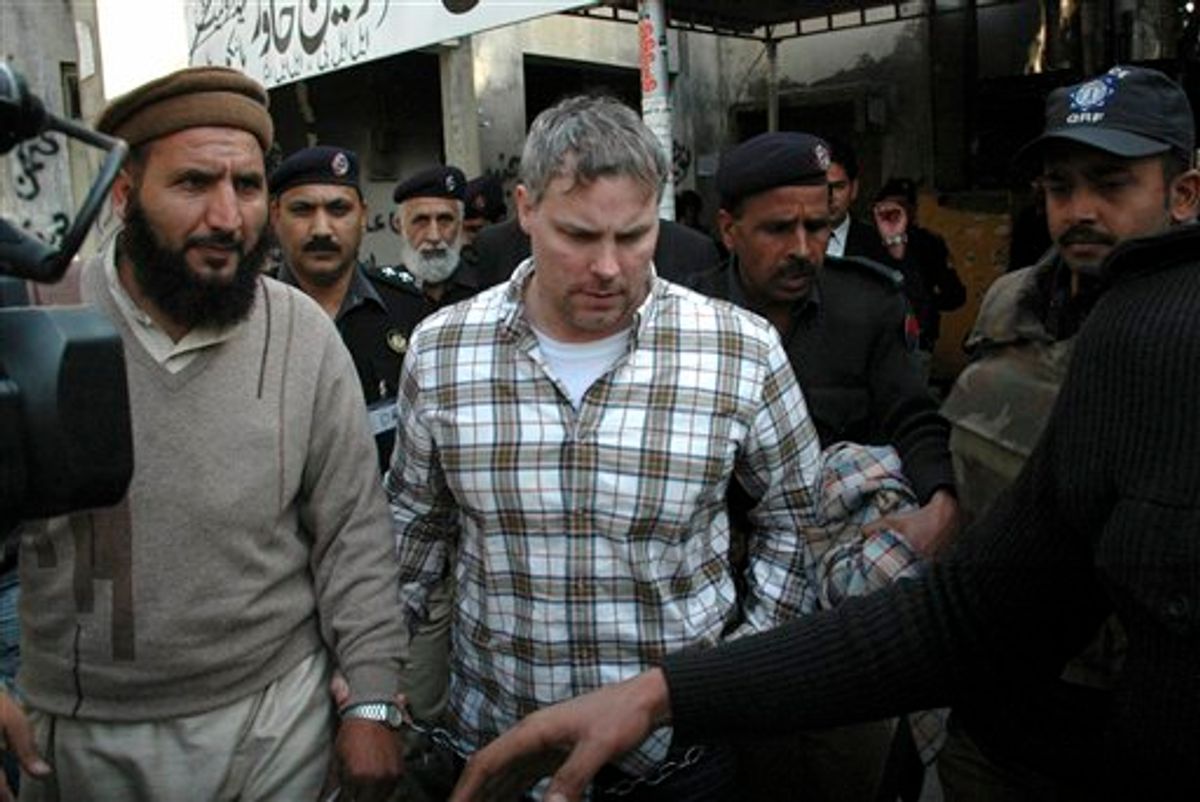

Davis, a former Special Forces soldier who left the military in 2003, was arrested Jan. 27 in connection with the fatal shooting of two armed men. Davis said he was defending himself against what he described as an attempted armed robbery as the men approached him on a motorcycle. A third Pakistani, a bystander, died when he was struck by an American consulate vehicle rushing to rescue Davis.

The two men in the response car have since left the country in what has been described by the Pakistanis as a concession to the U.S. Davis was carrying a Glock handgun, a pocket telescope and papers with different identifications.

The State Department maintains that Davis is an accredited member of the technical and administrative staff of the U.S. Embassy in Islamabad. U.S. officials said that the Pakistani government had been informed of his status in January 2010 and that Pakistan is violating its international obligations by continuing to hold him.

Under international law, diplomats are extended a degree of immunity from criminal prosecution in the countries where they are posted.

U.S. lawmakers have raised the possibility of cutting off U.S. aid to Pakistan if it continues to hold Davis. Earlier this month, House Armed Services Committee Chairman Howard "Buck" McKeon, R-Calif., and Rep. John Kline, R-Minn., bluntly told senior Pakistani officials during a trip to the country about the ramifications of their actions.

"I think it is imperative that they release him," Kline told reporters at a news conference, adding there is certainly the possibility that there would be repercussions if they don't.

Associated Press writers Adam Goldman and Donna Cassata in Washington and Nahal Toosi in Islamabad contributed to this report.

Shares