If you can't be a creator, you might as well play the muse. That was the deal, such as it was, that noted feminist and fiction writer Anne Roiphe made in the early 1950s -- and so did countless other women with serious aspirations, literary and otherwise. She attended parties with great talents like George Plimpton and Norman Mailer, where intellectual debate took center stage, but women were not a part of the main act. "The weight in the room, the power in the room, that was all male," she writes. As for the women on the edges of these conversations: "Beauty was an asset. It always is in a Harem." So, Roiphe utilized that asset.

Her tumultuous and unmoored 20s are the subject of her new memoir, "Art and Madness: A Memoir of Lust Without Reason." The male artists of her time embarked on their hero's journey, fueled by whiskey and sex; meanwhile, she was motivated by her romantic belief in the supreme importance of artistic creation, and a lack of options. As early as college, she felt an "overwhelming desire to bring coffee to the side of a writer, to wash his socks, to stare down his enemies, internal or external" -- to be his caretaker. Once married, she typed out the manuscript of her philandering playwright husband instead of hammering out her own masterpiece. At the time, she believed that the "wives and girlfriends of artists had a great task: to pay bills, to supply meals, to keep fear of poverty at bay so creation could continue." Post-divorce, and with a child, Roiphe had flings with and fielded late-night calls from drunken, and married, authors.

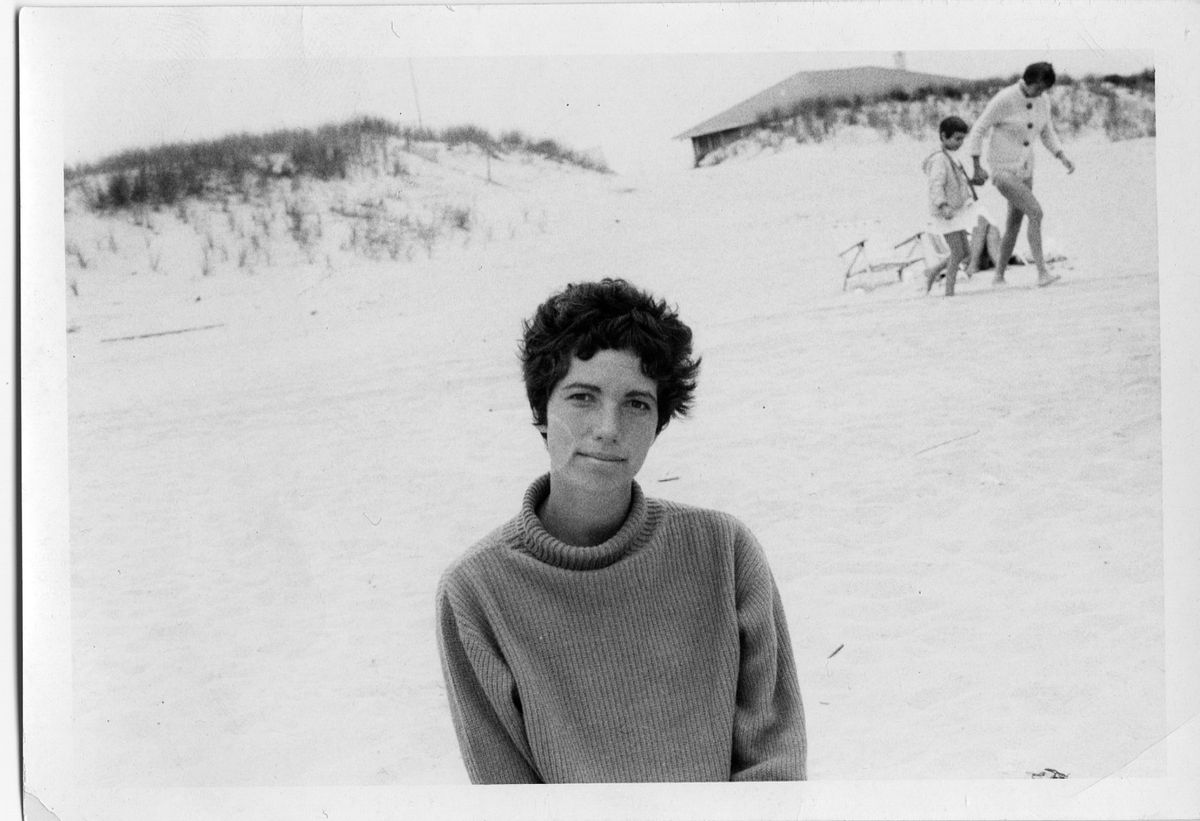

It was better than the alternative. As she saw it then, "Women who had married doctors and lawyers, stockbrokers and dealers in real estate or politicians had settled, had lost hope." Roiphe describes a fling with a man during a party at Plimpton's house. "His wife was in the living room and her babies were home with the nanny and my heart was broken because this wasn't what I really wanted -- to be a dark thick-haired girl who was had in someone else's bathroom," she writes. "On the other hand I didn't want to be a suburban housewife waiting at the train station for a husband who had taken a secretary to the bathroom earlier in the afternoon."

It was hardly just a cynical weighing of options or self-sacrifice in the name of art, though. Her romantic regard for art became a sort of lust for those who were doing the creating. These were men of great charisma, magnetism and romantic allure. "These kings of the hill were jostling for prizes named and unnamed and sometimes I was one of those prizes which was fine with me," she writes. That was true "even when I knew the man was a snake charmer and I was a snake."

Roiphe, author of "Up the Sandbox," tells a familiar story of a woman seeking to achieve through men, rather than on her own terms -- simply because it was all that she could envision for herself at the time. But her book is also uniquely honest, emotionally complex and utterly readable. She is, after all, a talented writer -- and this book tells the story of how she came to embrace that. It's rather poetic that several decades later, her second daughter, Katie Roiphe, who published her first book at the ripe age of 25, lamented that contemporary male authors "are so self-conscious, so steeped in a certain kind of liberal education, that their characters can't condone even their own sexual impulses."

What kind of satisfaction did you find in these relationships with the male literary talents of the time?

Well, I suppose that I found the same satisfactions that any young woman of that age would find with whatever fellow she was hanging around with. There was a sense of excitement and there was a sense that something important was happening -- as opposed to if I had married a golf pro, for example. I felt this was an important endeavor, and there was a kind of excitement that came from the creative energies all around. In a feminist world, those same excitements would be coming from the women as well as the men, but this was a pre-feminist world.

It seems there are still faint echoes today of this tendency for women to look to achieve through men, or to at least gravitate toward the sort of male power that they want.

I really can't speak to what's going on today -- you have to do that. I will say that it seems to me that women today have reason to expect so much more of themselves. They don't have to delay or submerge their own ambitions and creative energies. The idea that you would grow up wanting to be someone's muse today is fairly laughable. But that was a very, very different world. I had never ever met, seen or gone to a woman doctor. Just a simple thing like that. It was a very different set of expectations, so it wasn't all that unreasonable that your ambitions would be explored through a male.

You say in the book that you had never had a conscious moment where you weren't wanting to be a writer.

That's true --until all of a sudden I forgot that.

And how did you forget?

Think about your average Jane Austen female character who, say, really, really wanted to be a writer -- but along comes this entire society that takes her to dances, and everyone is looking at her expecting her to make her choice. Her fortune is going to be made, not by what she's got in her head but by her choice here. The way I would explain it is I didn't exactly do what was expected of me, but, emotionally, I did do what was expected of me, which was to attach my fortunes to a male. It certainly didn't seem strange; at the moment, it seemed reasonable.

Right. You were a young woman who wanted very much to be a writer, so you surrounded yourself with these creative sorts and particularly male talents.

That's right, and it wasn't just me. There were a lot of women who were doing this. Let's say you were interviewing a woman who had become a gangster's moll and all her life she'd wanted to be near the center of power in her community. If she had the physical beauty, she might have married the top gangster. You can understand why she would do that, because she's not going to become head of the mob. That's essentially what was going on.

How was it that you transitioned from this total devotion to art and to someone else's creation to actually creating your own work?

Maybe we call it growing up, and the times changed somewhat, though I think I changed slightly before they did. I was divorced, I had a child, I had to live a life. This was not an option. Now, I could have retreated and found somebody from my mother's country club to protect me, but by that time I knew that there were things I could do. It's the difference between being 21, which is how old I was when I got married, and 28.

Another interesting revelation in your personal storyline is that you go from having this romantic, almost religious, regard for art and its creation to being very businesslike and pragmatic in how you go about writing, that it's just work. It loses its magical allure. Was that just a gradual change?

Romanticizing the act of writing or any other art is not very helpful to the artist or the art. It's much better if one simply does. It worked better for me when I was just a writer, a working person. I've never felt that I needed a special desk with a special light coming in from the window at a special angle. It's work, not so different from that way you fix dinner or you pick up a child at school.

I'm curious what you thought of your daughter Katie Roiphe's piece about the flaccid sexuality of the male literary talent of today. It's such a stark contrast to the period that you're writing about.

I think Katie is a very, very keen observer. It seems to me that she was observing some of the fruits of the movements of which I had been a part. What we're seeing is the difference between her generation and my generation and what my generation was able to give to all of you was a completely different sense of family life, artistic life and male and female relationships.

Shares