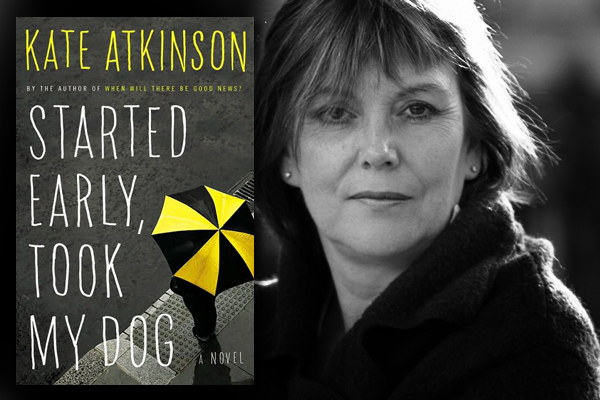

“Started Early, Took My Dog” is the fourth of Kate Atkinson’s Jackson Brodie novels (the others are, in order: “Case Histories,” “One Good Turn” and “When Will There Be Good News?”), so there can be no doubt about it: We’ve got a series here. About this, I am ambivalent. Each one of these books, including this latest, is a delight: an intricate construction that assembles itself before the reader’s eyes, populated by idiosyncratic, multidimensional characters and written with shrewd, mordant grace. They are in some respects mystery novels, but they’re written with a literary skill uncommon in that genre, and in a mode — the tragicomic — that few but the most adept novelists can pull off in any genre. Atkinson’s Jackson Brodie books are like high-wire acts in which she is forever defying gravity (in the form of crime fiction’s improbable conventions) by making the work fresh, unpredictable and alive. Can she really keep it up if Jackson’s adventures stretch out ad infinitum, like those of Michael Connelly’s Harry Bosch?

This time around, Atkinson’s theme is the appalling miracle of love, specifically the love that a grown-up person feels for someone much smaller, younger and more vulnerable. That’s the emotion that poleaxes Tracy Waterhouse, a 50-ish retired policewoman working mall security, when she spots a familiar “scrag-end of a woman,” a local prostitute, dragging a 4-year-old girl through a crowd. On a fateful impulse, Tracy pays the woman the cash she was going to spend on a vacation to hand over the child.

Jackson, a former cop and semi-retired private detective, succumbs to a lesser form of this sentiment when he rescues a border collie from its loutish, abusive owner on the same day. Both adoptions occur in Leeds, a city in Yorkshire near where Jackson grew up and where Tracy spent the best years of her life trying to curb the damage done by the worst aspects of human nature. The resentment that the salt-of-the-earth northern English feel toward their sleeker southern countrymen is a running theme in Atkinson’s work. When Jackson, in time-honored PI fashion, gets beat up by a couple of thugs, the kicks and punches bother him less that the fact that they take him for a southerner. (It’s a bit like mistaking a Mississippian for a Yankee.)

What Tracy soon feels toward her illegally procured child is an “overwhelming, gut-wrenching, lay-down-your-life kind of love.” It turns her life upside down and sends her on the lam, just at the moment Jackson shows up asking inconvenient questions about a murder Tracy worked on at the beginning of her career. His client is a woman in New Zealand trying to find her birth parents, a quest complicated by the fact that no record of her adoption or even of her birth can be found.

Tracy doesn’t have many illusions left: She missed watching Charles and Diana’s wedding on TV because she was “coordinating house-to-house after the so-called honor killing of a woman in Bradford.” Like Jackson — and Louise Monroe, a Scottish police detective who appeared in the two preceding novels and for whom Jackson pines from afar — she is a battered veteran of the war against the (undeclared) war against women. A slender thread of references to Peter Sutcliffe, the Yorkshire Ripper, runs through this novel. Sutcliffe targeted mostly prostitutes and other “throwaway” females, and the blokeish male policemen Tracy worked with as a rookie still shake their heads at the notion of raising a fuss when such women turn up dead. (Sutcliffe, quoted in this novel’s epigraph, described himself as “just cleaning up the place a bit.”)

Like Jackson, Tracy keeps a curmudgeonly commentary constantly running in her head. Thinking about shoplifting leads to thinking about consumerism leads to the rumination that “Western civilization had had a good run of it but now it had pretty much shopped itself out of existence.” But Tracy, unlike Jackson, watches a lot of TV, and in a lovely touch, her metaphors are tinted by that: Her green bathroom fixtures are “the color of Shrek,” and the woman she “buys” Courtney from “suddenly meerkatted to attention” when Tracy mentions the subject of money.

Atkinson’s other fed-up point-of-view characters include an aged actress playing the mother of a detective on a TV show both Jackson and Tracy detest; the gradual erosion of this woman’s mind from dementia is harrowingly rendered. Then there’s Tracy’s former partner, Barry, the literary equivalent of those retrograde career coppers on “Prime Suspect” and “Life on Mars” (British version only, please!), rendered somewhat more sympathetic by the loss of his own daughter and grandchild. The terror of parenthood haunts this novel far more pervasively than any murderer. The plot is (blessedly) less Byzantine this time around, but the bottom notes in the emotional register of “Started Early, Took My Dog” are deeper than those of the preceding three novels.

And then there’s Jackson, who at this point — having won a fortune, then lost it to a wife who turned out to be a con artist, then undergone near-death in a train derailment — is a knight errant, roaming the countryside, righting wrongs, or at the very least, turning up in the wrong place at the right time with implausible frequency. He is the Good Man in Atkinson’s universe, which means in part that he sticks to what he loves. There’s a perpetual tug toward attachment in his personality that makes him absurdly jealous when he hears the feminine voice of his own GPS device (he calls it Jane) emanating from another man’s car. How long can Atkinson keep him on the road before his peregrinations — and his tendency to land, Nancy Drew-style, in the middle of mystery after mystery — begin to seem hopelessly contrived?

I’d hate to see Jackson Brodie turn into a character of convenience like Harry Bosch — who is fine, I guess, just not very interesting. Somehow, it would seem like a violation of Atkinson’s transfiguration of the crime narrative if she allowed him to shamble around like this forever. Fortunately, there are signs at the end of “Started Early, Took My Dog” that Jackson’s life may be in for a serious change. And there’s the dog, of course, a winning hound who deserves a better name than the one Jackson picks for him (“the Ambassador”? Really?) and who, above all, needs a good home.