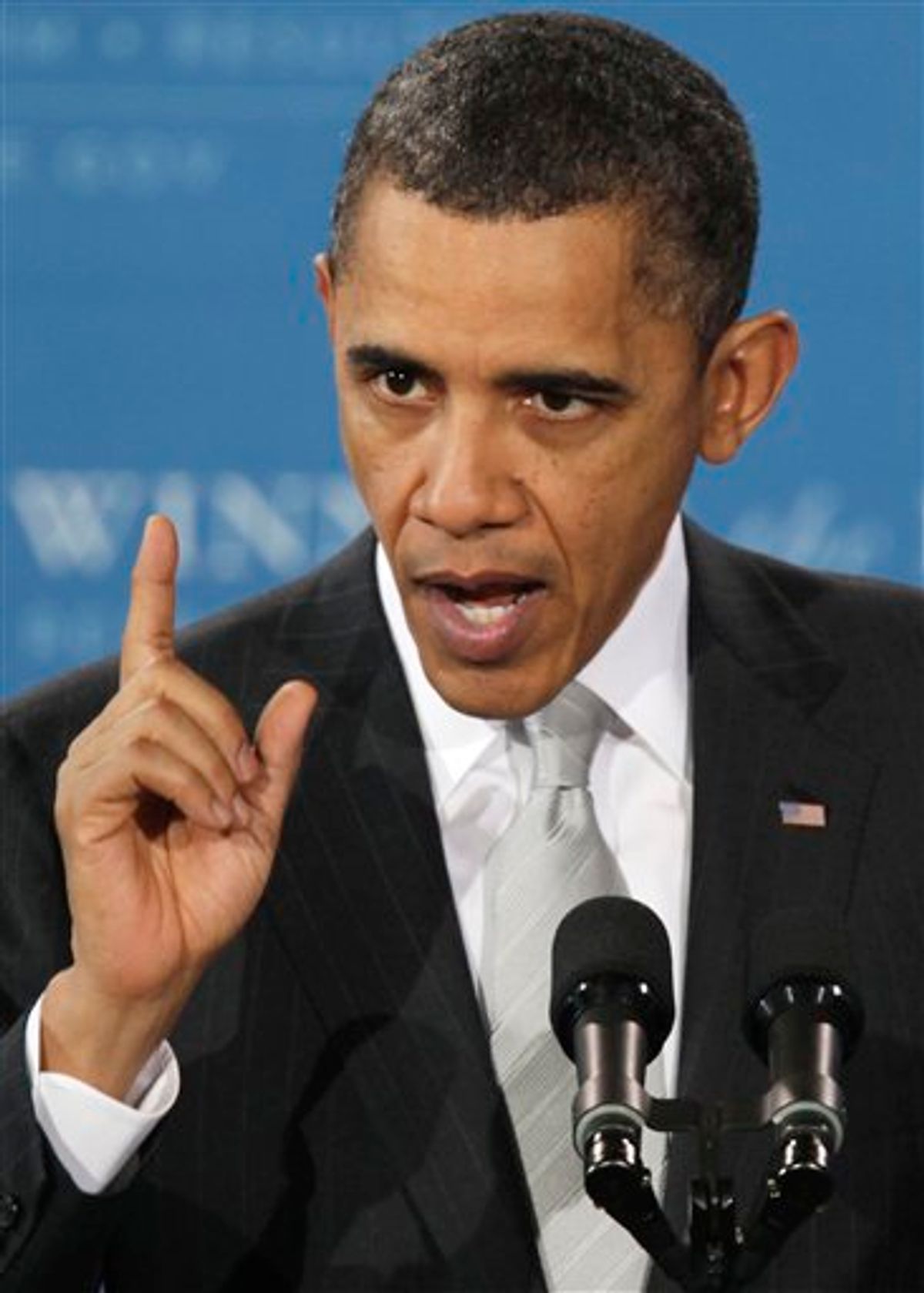

In October, 2007, candidate Barack Obama -- in response to the Bush administration's demand for a new FISA law -- emphatically vowed that he would filibuster any such bill that contained retroactive amnesty for telecoms which participated in Bush's illegal spying program. At the time, that vow was politically beneficial to Obama because he was seeking the Democratic nomination and wanted to show how resolute he was about standing up against Bush's expansions of surveillance powers and in defense of the rule of law. But in a move that shocked many people at the time -- though which turned out to be completely consistent with his character -- Obama, once he had the nomination secured in July, 2008, turned around and did exactly that which he swore he would not do: he not only voted against the filibuster of the bill containing telecom amnesty, but also voted in favor of enactment of the underlying bill. That bill, known as the FISA Amendments Act of 2008, was then signed into law by George W. Bush at a giddy bipartisan signing ceremony in the Rose Garden, which -- by immunizing telecoms and legalizing most of the Bush program -- put a harmless, harmonious end to what had been the NSA scandal.

Beyond telecom amnesty, the FISA Amendments Act also wildly expanded the Government's power to conduct warrantless surveillance of telephone calls and emails. In large part, the bill was intended to legalize the illegal Bush NSA program that had caused so much faux controversy among Democrats. As Yale Law Professor Jack Balkin put it: "Through the FISA Amendments Act of 2008, Congress has legitimated many of the same things people are now complaining about"; separately, Balkin contended that Obama voted for the bill because, as President, he himself would want the same powers Bush had to intercept people's communications without bothering with court approval.

When trying to placate his numerous supporters furious over his reversal, Obama insisted he voted for the bill with "the firm intention -- once I'm sworn in as president -- to have my Attorney General conduct a comprehensive review of all our surveillance programs, and to make further recommendations on any steps needed to preserve civil liberties and to prevent executive branch abuse in the future" (that promise caused his then-large band of faithful followers to evangelize that Obama only voted for the bill to make sure he won the election, so that he could then use his majestic power to fix civil liberties abuses of the type he had just voted for; that was when people were still willing with a straight face to invoke the 11-dimensional chess justification for everything he did). Needless to say, it would have been unhealthy in the extreme holding one's breath for that "we'll-fix-it-when-I'm-President" promise to be fulfilled, as -- more than 2 years into his presidency -- nothing like it has remotely happened.

Immediately upon enactment of the Bush/Obama-supported FISA Amendments Act, the ACLU filed a lawsuit seeking to enjoin its enforcement on the ground that the law's expanded warrantless eavesdropping powers violated the Fourth Amendment. Aside from its warped and radically enlarged "state secret" doctrine, the Bush administration's standard tactic for avoiding judicial review of their illegal eavesdropping programs was a two-step "standing" exercise grounded in extreme cynicism: (1) they shrouded their eavesdropping actions in total secrecy so that nobody knew who was targeted for this eavesdropping, and they then (2) exploited that secrecy to insist that since nobody could prove they were actually subjected to this eavesdropping, nobody had "standing" to contest its legality in courts (that's how the Bush DOJ got an appeals court to dismiss on procedural grounds a lower court ruling that their NSA program broke the law and violated the Constitution).

In the case brought by the ACLU, the plaintiffs were a variety of human rights activists, lawyers and journalists (including Naomi Klein and Chris Hedges), who argued that both they and their sources have a reasonable fear of being subjected to this expanded surveillance, and that fear-- by rendering them unable to perform their jobs and exercise their Constitutional rights -- constitutes sufficient harm to vest them with "standing" to challenge the new eavesdropping law. In response, the Bush administration argued -- as always -- that the plaintiffs' inability to prove that they were actually targeted by this expanded surveillance precluded their suing; their mere "fear" of being targeted, argued the Bush DOJ, was insufficient to confer standing to sue.

In late 2008, a lower court judge granted the Bush argument and dismissed the ACLU's lawsuit on "standing" grounds. On appeal, the Obama DOJ -- needless to say -- faithfully adopted exactly the Bush argument to demand dismissal of the ACLU's lawsuit on procedural grounds of "standing," i.e., without assessing the merits of whether this law violates the Fourth Amendment.

But today, a three-judge appellate court dealt a serious blow to the Bush/Obama tactic for shielding government eavesdropping from judicial review (i.e., placing secret executive surveillance above and beyond the rule of law). The unanimous court ruled that the plaintiffs' fear that they will be subjected to this expanded warrantless eavesdropping is reasonable given the sweeping powers the law vests in the Executive, that these fears substantially impede their work, and that these impediments constitute actual harm sufficient to allow them to challenge the constitutionality of the FISA Amendments Act:

This may sound like a legalistic development but its significance extends far beyond that. Unlike the bastardized Bush/Obama "state secrets" weapon for avoiding judicial review, "standing" is actually a legitimate and important constitutional restriction on a court's jurisdiction. The idea is that courts are permitted to resolve only actual disputes between actual parties where the defendant's conduct has uniquely injured the plaintiff in direct ways; we don't want courts to be free-floating, omnipotent tribunals that issue binding answers to every abstract political question. They are empowered to issue legal rulings only when there is an actual "case or controversy" before them involving parties directly and uniquely harmed by the challenged conduct.

But what the Bush DOJ and then the Obama DOJ have done is manipulate that important "standing" limitation beyond all recognition into a weapon of full-scale presidential immunity. If one were to accept their tactic, a President need only break the law in total secrecy and prevent anyone from finding out what exactly he did and to whom he did it. With that secrecy in place, the DOJ can then tout that secrecy as a means of preventing any judicial challenges to the President's conduct -- which is another way of saying that the President has placed his conduct outside of the rule of law (because we did it in secret, everyone is unable to sue over it). Obviously, if one can break laws but then block courts from adjudicating allegations of lawbreaking, then one is -- by definition -- free to break the law. That has been the case thus far with the Bush administration thanks to the warped doctrines it pioneered and the Obama DOJ then swallowed whole.

This danger is particularly acute in the post-9/11 world where so much of what the Executive branch does of any significance -- I'd say most of what it does -- takes place behind a wall of secrecy. To allow Presidents to escape all legal challenges on "standing" grounds merely because they managed to conceal the identity of the victims of their lawbreaking would be, in essence, to have laws that apply to Presidents only in theory but not in reality.

Today's ruling puts at least some brakes -- for now -- on that license of lawlessness. It rejected the Bush/Obama claim that citizens must prove they have been targeted by an illegal presidential program before they have the right to ask a court to declare it illegal. Instead, a plaintiff's reasonable fear that their rights are being violated due to enactment of an allegedly unconstitutional law -- combined with actual harm suffered as a result of that fear -- suffices to allow them to challenge the legality of those actions. It is, of course, possible that the Supreme Court can review and reverse this ruling, but the Second Circuit is a well-regarded court -- situated on the level immediately below the Supreme Court -- and this well-reasoned decision will have significant sway. At the very least, this is an important ruling in eroding what is easily one of the worst political problems plaguing America in the post-9/11 world: the ease with which Presidents and their underlings can insulate their secret actions from the rule of law.

Shares