This piece originally appeared in NewDeal 2.0.

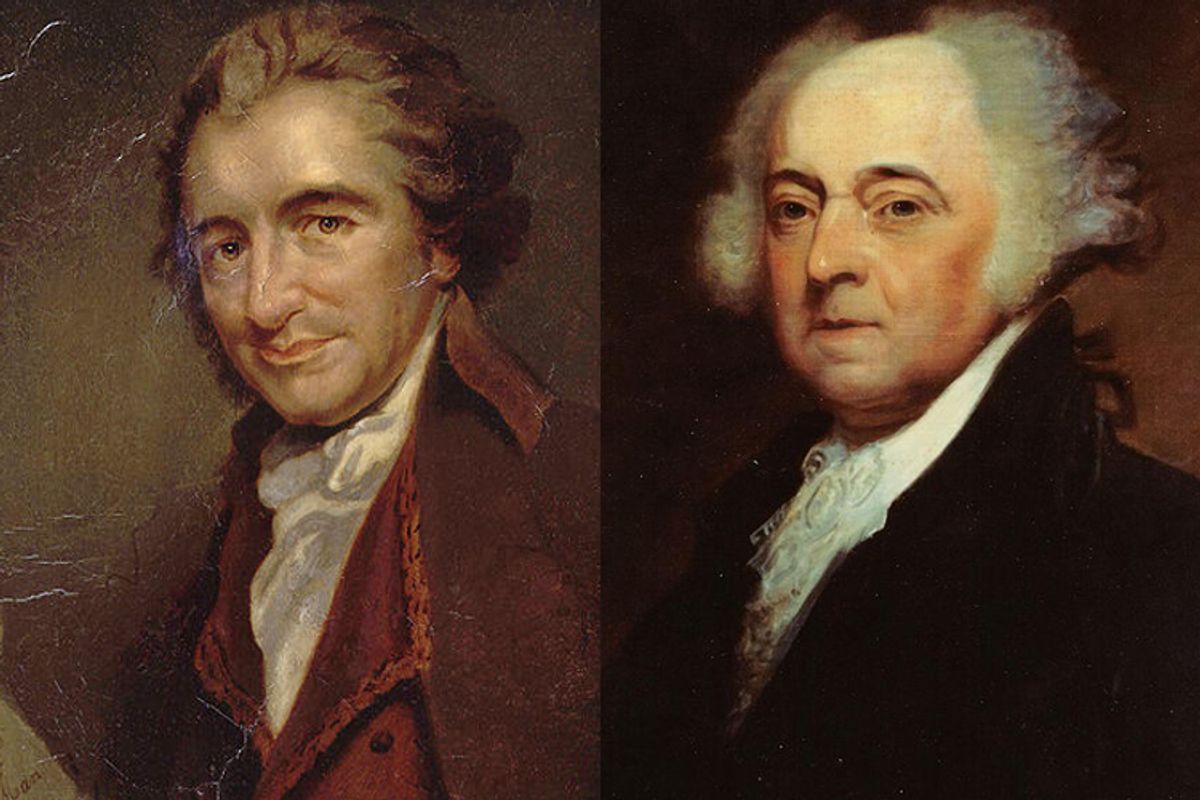

Here's John Adams on Thomas Paine's famous 1776 pamphlet "Common Sense": "What a poor, ignorant, malicious, short-sighted, crapulous mass." Then comes Paine on Adams: "John was not born for immortality."

Paine and Adams may have been alone among the founders for having literary styles adequate to their mutual disregard. "The spissitude [sic!] of the black liquor which is spread in such quantities by this writer," Adams wrote of Paine, "prevents its daubing." Paine: "Some people talk of impeaching John Adams, but I am for softer measures. I would keep him to make fun of."

They went on and on.

The Paine-Adams antipathy wasn't just personal. Its sources lay in the founding generation's deep political divisions over economic equality. Those who don't know there was a founding political division over economic equality can thank the many historians -- including even some biographers of finance-savvy founders like Superintendent of Finance Robert Morris -- who feel more comfortable with philosophies of government, issues in constitutional law, and (if they get into economics at all) the legacies of Robert Walpole, Jacques Necker and David Hume than with day-to-day American economic realities, and with the full range of 18th-century thinking from elite to working-class, on monetary and finance policy.

Things John Adams hated about "Common Sense" are revealing. One was the pamphlet's widespread reputation as the tipping point for America's declaration of independence from England. Adams thought that was nonsense. The only novel thing in "Common Sense," Adams believed -- and he meant it in a bad way -- wasn't what he cast as its belated, derivative call for American independence. It was what he blasted as Paine's "democratical" plan for a new kind of American government, which flew in the face of the balanced republicanism that Adams loved. That part of the pamphlet was its only important part to John Adams, but it is often ignored or glossed over in favor of celebrating what Adams thought the pamphlet never did: persuade Americans to support independence.

In proposing a new American government, Paine scoffed caustically at the whole idea of balance and the covalence among branches that we're taught to revere as exceptionally American, but were really derived from the post-Settlement English constitution. Where Adams saw checks and balances as key to liberty, Paine wanted an executive branch subordinated to a hyper-representative legislature (a single house, with no check from any elite "upper" house) and a judiciary directly elected by the people.

Most horrifying to Adams, Paine wanted citizens to have the vote regardless of property ownership. While in "Common Sense" Paine dialed back his thoughts on equality, arguing only for easy access to the franchise, in other works he promoted smashing the ancient equation that liberty-loving Whigs had always made between property and representation. Paine wanted the less propertied and -- horrors! -- even the unpropertied not only to vote in a free America, but also to hold office.

Paine's goal in giving the lower sort and the poor access to political power was economic equality. When ordinary Americans held power, they would pass laws promoting the interests of ordinary Americans -- and obstructing, not coincidentally, the interests of finance elites. And that's just what happened in Pennsylvania beginning in 1776, when Paine's friends wrote a constitution for that state, based largely on Paine's ideas, removing the property qualification for the first meaningful time anywhere. Assemblies elected under that constitution passed anti-monopoly laws, worked to bring about government debt relief, and took away the charter of the bank founded by the high financier Robert Morris for the purpose of enriching himself and his friends.

The ideas in "Common Sense" that John Adams feared and loathed became realities in Pennsylvania. Many historians celebrating Paine's goals of liberty and independence fail to acknowledge that for Paine, those goals were inextricable from political equality for the people he spoke for: ordinary working Americans.

One of the most fascinating moments in Paine's career therefore occurred when he went to work for the high financier Robert Morris himself, writing at Morris's behest on behalf of federal taxation in the service of national unity. Paine's democratic populist friends saw Morris's taxes, and indeed Morris's wish for national unity, as a means of shoring up American wealth and pushing back the economic gains ordinary people had made in the Revolutionary period. Paine excoriated Morris for chicanery during the Revolution and helped create the economically democratic government that took away Morris's bank and made the fat cat investor accountable to public opinion. In the 1780s, sudden support for Morris's nationalist finance made Paine look like a sellout. He lost friends among his 1776 allies for equality.

But unlike many of his populist friends, Paine wanted a strong national government for America. Many economic populists of the period made the mistake of placing hopes for popular finance in antifederalism and then in the emerging "states rights" thinking of the anti-Hamilton elites. Populists had reason to feel more sympathy for state governments than for a national one: legislatures from time to time had been susceptible to the will of the less enfranchised, expressed through rioting; states had issued paper currencies and established land banks. And nationalists like Morris and Hamilton were indeed out to end all that. They wanted to make finance and monetary policy national matters, empowering suppression of debtor riots and enforcement of taxes collected for the benefit of an interstate money elite.

Paine, however, was impatient with the anti-nationalism of his fellow democrats. Skeptical of knee-jerk populism, he had high hopes for national finance. The strangest of bedfellows, Paine and Morris were working together at weird cross purposes. Paine's vision, diametrically opposed to Morris's, was like Morris's in being a national one. Along with "the madman of the Alleghenies" Herman Husband, who also saw through state-focused elites' pandering to populism and thought an egalitarian national government might be better empowered to hold greed in check, Paine's radical democracy made him an offbeat kind of Federalist. Gazing farther than most of the popular finance activists of his time, he looked for a strong national government that would amplify the democratic gains he'd helped achieve in Pennsylvania.

The United States government, in Paine's vision, would justify its national power by regulating elite finance throughout the states, promoting the interests of ordinary Americans everywhere, and increasing social equality by law. For Thomas Paine, American finance policy must dedicate itself to economic equality.

William Hogeland is the author of the narrative histories "Declaration" and "The Whiskey Rebellion" and a collection of essays, "Inventing American History." He has spoken on unexpected connections between history and politics at the National Archives, the Kansas City Public Library, and various corporate and organization events. He blogs at http://www.williamhogeland.com.

Shares