In March 1949, a group of Illinois college students traveled to Springfield, Ill., to protest a group of anti-Communist subversion bills introduced by state Sen. Paul Broyles, the chairman of the Seditious Activities Intelligence Commission. Broyles wanted to outlaw the Communist Party, make membership in a Communist "front organization" a felony, and require all public-sector workers -- including public school teachers and university professors -- to swear loyalty oaths.

The protests drew wide attention and prompted the hasty passage of a joint resolution declaring that "It appears that these students are being indoctrinated with Communistic and other subversive theories contrary to our free systems of representative government." A public investigation of whether University of Chicago professors were responsible for such indoctrination followed, but mostly fizzled out after a bravura performance by University of Chicago chancellor Robert Hutchins.

Hutchins later reflected on his experience.

Since a university faculty is a group set apart to think independently and to help other people to learn to do so, it is fatal to force conformity upon it. Nobody would argue that all professors must be members of the Republican Party; but we seem to be approaching the point where they will all be required to be either Republicans or Democrats (right wing).

I do not claim that the status of university professor should entitle a man to exemption from the laws. But I do say that imposing regulations that go beyond the laws is impractical and dangerous.

There are fashions in opinion as well as in behavior. We are just emerging from an era in which a schoolteacher could lose her job by smoking, dancing, or using cosmetics. We should avoid entering one in which a professor can lose his post and his reputation by holding views of politics, economics, or international relations that are not acceptable to the majority.

This is thought control.

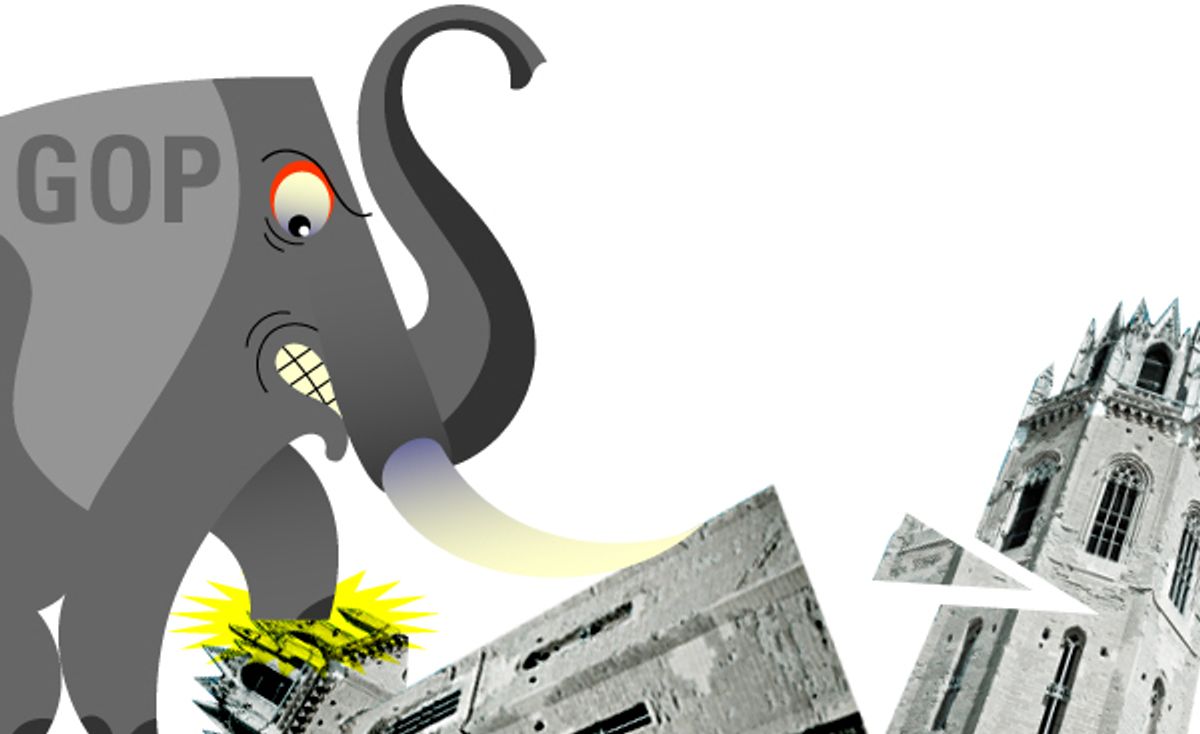

It is a little amusing to note Hutchins' worry that all professors might be required to be right-wing, in light of the current conservative gripe that universities are dominated by left-wing "tenured radicals" who enforce their own dogmatic thought control on today's students. But it's certainly no joke to today's public university faculty when politically motivated opponents start gunning for them, for whatever ideological reason. I stumbled across the Illinois episode while researching the issue of legal restrictions on political activity by public sector employees -- a sizzling topic in the wake of the Open Records request made last week by the Republican Party of Wisconsin that seeks access to University of Wisconsin history professor William Cronon's e-mails. (In fact, if you Google the words "political activity by public university employees" the first result returned is the University of Wisconsin's guide to what is permitted and prohibited.)

The political heat is set particularly high in Wisconsin, but the Cronon affair is hardly an isolated incident. On Tuesday, Talking Points Memo's Evan McMorris-Santoro reported that a conservative think tank in Michigan is also using FOIA requests to gain access to emails sent or received by academics at three Michigan public university departments, suggesting that there is a concerted effort by the right to go after any kind of labor activism occurring in a public university academic context. The historical echoes are pretty easy to hear. In the 1950s, the enemy was Stalin. In 2011, it's unions, period.

Which is not to say that the Mackinac Center for Public Policy doesn't have a legitimate case against Wayne State University's Labor Studies Center. I would not be at all surprised to learn that academics who have devoted their careers to studying labor history or labor economics might want to apply theory to reality, and help directly organize workers. In a state with such a potent labor history as Michigan it would be more surprising if they weren't. I'm not exactly sure how different that is from right-wing economists pushing free-market fundamentalist policy positions, but there are clearly pretty strict rules on what public university employees -- or any government employee -- can do in the political realm using their employer resources, dating all the way back to the Hatch Act of 1939.

We don't want government employees improperly influencing the political process. But drawing the line for what is appropriate for a teacher can get very tricky. And I don't think I am the only person who is troubled by the fact that at the very same time that conservatives are attempting to stamp out every last vestige of labor activism that might benefit from the taxpayer dollar, restrictions on the ability of corporations and well-capitalized special interests to influence the political process are being shredded. Unions may have once represented a "countervailing force" to the power of big capital, but they do so no longer. For all intents and purposes, the corporations have won. The spectacle of the ongoing evisceration of the Dodd-Frank bank reform bill, which was never very strong to begin with, in tandem with the incredible growth in financial sector profits so soon after one of the greatest financial crises in the history of the United States, tells us all we need to know on that front.

If we are scrupulous, we might be able to limit ourselves to rules that clearly demarcate appropriate behavior: such as a ban on using .edu addresses to support the recall of a politician or organize a picket line. But the history of our country tells us all too clearly that it is far too easy for overzealous partisans to go too far, and start implementing their own form of "thought control" by investigating "indoctrination." What happens when a professor lectures so brilliantly on the role of the labor movement in reducing income inequality in the United States that students rush from his or her class to join a protest? When does that become verboten?

In between defeating Germany in World War II and serving as president of the United States, Dwight D. Eisenhower was the president of Columbia University. In his "Installation Address" he made a stirring declaration:

There will be no administrative suppression or distortion of any subject that merits a place in this University's curricula. The facts of communism, for instance, shall be taught here -- its ideological development, its political methods, its economic effects, its probable course in the future. The truth about communism is, today, an indispensable requirement if the true values of our democratic system are to be properly assessed. Ignorance of communism, fascism, or any other police-state philosophy is far more dangerous than ignorance of the most virulent disease.

Who among us can doubt the choice of future Americans, as between statism and freedom, if the truth concerning each be constantly held before their eyes? But if we, as adults, attempt to hide from the young the facts in this world struggle, not only will we be making a futile attempt to establish an intellectual "iron curtain," but we will arouse the lively suspicion that statism possesses virtues whose persuasive effect we fear.

It would have been nice if Eisenhower had lived up to this sentiment a little more as president during the worst of the McCarthyite hysteria, but let's take him at face value anyway. We need our universities, public and private, to be places where academics feel free to pursue whatever line of thought they want. If that pursuit spills over to action, we should be careful about what restrictions we try to enforce. Better, by far, to err on the side of freedom, because that, theoretically, is what this country is all about.

Shares