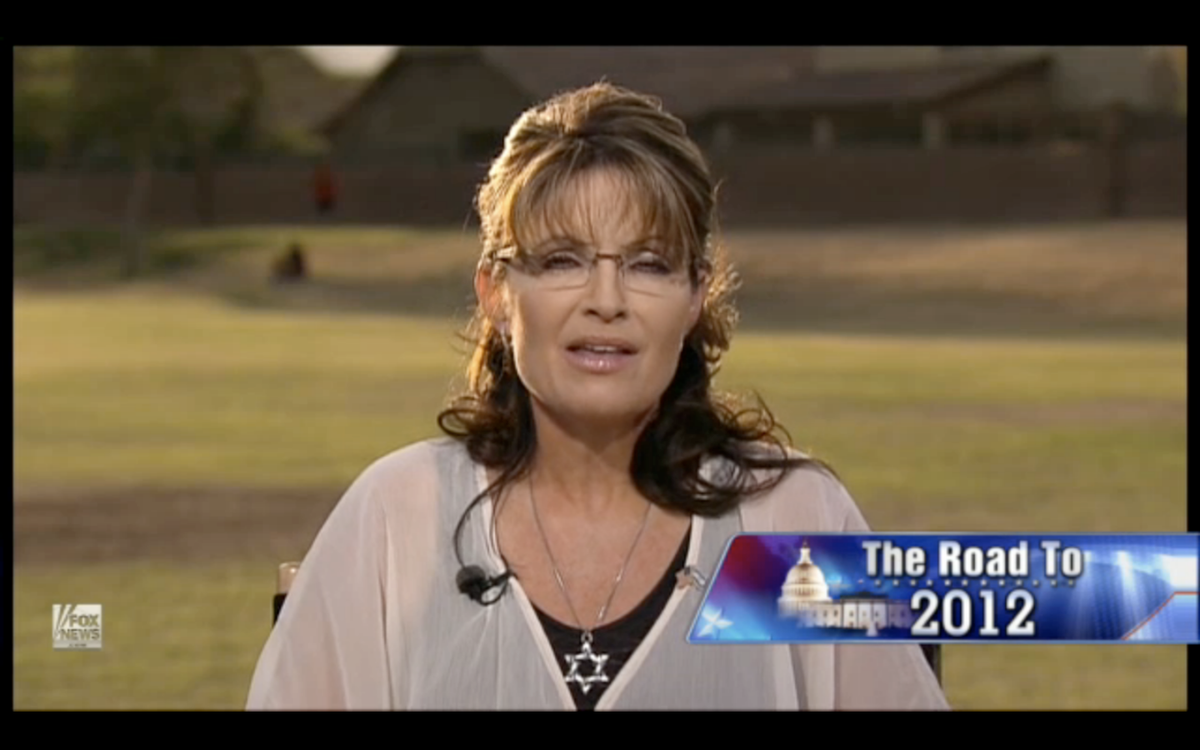

While we were all falling for John Boehner's head fakes last week, a poll was released that probably deserved more attention than it received. After all, it contained the strongest evidence yet that Sarah Palin has been thoroughly and completely marginalized as a national political force.

The NBC News/Wall Street Journal survey found the former Alaska governor's popularity at all-time low, with just 25 percent of Americans expressing a positive opinion of her -- and 53 percent a negative one. This was the worst score for any of the American politicians measured (although if it’s any consolation to Palin, she did fare better than Moammar Gadhafi, who clocked in with a two percent favorable rating) and represented an 18-point spike since last September in Palin's negative rating.

The poll also found her falling back in the 2012 GOP horserace. Not long ago, she routinely finished at or near the top in '12 trial heats; now she's back in fifth place, with just ten percent.

It's hard to look back at the last six month and pinpoint one precise moment when the bottom fell out for Palin (although her response to the shooting of Gabrielle Giffords, panned as tone deaf by even many of her fellow Republicans, comes close). But at some point recently, she stopped simply being a polarizing lightning rod -- one with as many fanatical followers as diehard critics -- and transformed into a figure who even Republican-leaning voters have a hard time taking seriously.

This is, obviously, a welcome development for pragmatic, bottom line-oriented Republicans. And, perhaps, a surprising one. In the immediate wake of last fall's midterms, it seemed only too easy to imagine Palin jumping into the '12 race, securing the GOP nomination and then squandering what otherwise might be a winnable November election for her party.

Sure, the GOP establishment was well aware of her general election liabilities -- just as they'd been aware of the Sharron Angle's and Christine O'Donnell's and Ken Buck's liabilities. But their frantic efforts to convince Republican primary voters to reject those Senate candidates last year and instead to embrace safer, more electable alternatives backfired horrifically. GOP primary voters wanted purity, not pragmatism, even if it meant leaving Senate seats on the table. It wasn't a stretch to suggest they'd be in the same mood in '12 -- seeing through Mitt Romney's (or Tim Pawlenty's or Haley Barbour's…) efforts to gain Tea Party credibility and instead opting for the real deal, Palin.

So what changed? The answer seems to be that even opinion-shaping conservatives -- the folks who had been making excuses for Palin -- woke up, probably because they grasped for the first time how serious her '12 prospects had become. As we've been tracking, commentators with deep credibility on the right began speaking up in the weeks and months after the November election, either casting doubt on her leadership skills or electability or making the case -- as Andrew Breitbart did -- that she's just too big for the presidency.

Conservative voters, it seems, began to get the message: It was OK to like Palin and to believe she was a victim of the left and its allies and to still conclude that she wasn't presidential material. By the end of December, polls began registering a marked uptick in Palin's unfavorable scores, even among Republicans.

Then came the Tucson shootings, after which the now-infamous "crosshairs" map on Palin's website became the focus of intense scrutiny. Palin's reaction was typical -- she portrayed herself an innocent victim of a liberal attack. And, to be fair, she had -- in this one instance -- a rather legitimate gripe. A connection -- direct or indirect -- between the old crosshairs map and Giffords' shooting was completely nonexistent. But what was revealing was the response of several prominent opinion-shapers on the right. Instead of backing up Palin's rage, they chastised her. Charles Krauthammer, for instance, called her statement "unfortunate and unnecessary." Krauthammer could have played it either way. It's hard not to conclude that his decision to join the Palin pile-on was rooted, in part, in a desire to decrease her chances of winning the nomination.

The occasional rebukes have continued since then, while Palin has made no apparent effort to mend fences with her party's opinion-shapers. As a result, there isn't nearly enough pressure now on rank-and-file conservative voters to go along with the crowd and pretend that the empress is wearing clothes.

Trying to predict what Palin will do in '12 is foolish. Maybe she'll run, and maybe she won't. But as time progresses, her decision seems less and less consequential. The Republicans who cheered her wildly in 2008 and defended her intently for the next two years seem to have decided to simply move on without her.

Shares