When I was 9 years old, my father went on a whirlwind trip to Europe to get over my mother, who had left him two years before. He did not say he still missed her, but if you said my mother’s name, he would squint as if the light were dim. My father, the lone cynic on a Christian motor coach tour, fell in love with Paris. He also fell in love with a high school teacher from Kansas, named Debbie Stone. That was the year after the film “Romancing the Stone” hit the theaters. “I’m in Germany, romancing the stone,” he joked on a postcard he sent me from Munich. The next postcard was from Lucerne: “I went all the way to Switzerland to meet a girl from Kansas.” It was there that he tossed his wedding ring into the polluted waters of the Rhone River.

Debbie Stone had the same crushing effect on my father that Kathleen Turner had on Michael Douglas. In his heart, my father fancied himself to be a cross between his own cinematic heroes — fast-talking, sarcastic Jack Nicholson and witty, neurotic Woody Allen — yet he was neither. He was neurotic, certainly, but that was because he yearned after what he couldn’t have. He could fall in love with a woman faster than he could tie his shoes, but his wit was not so fast. It could not catch up with the speed of his heartbreak.

When my mother left, I became my father’s confidante. Through the divorce, I comforted him, saying it was not his fault, and I was only vaguely aware that this was probably a lie. After all, he was jealous, irritable and obsessive to a fault; he pursued foolish things and people without regard to their probable outcomes. After more than a decade of marriage, my mother must have been tired.

Yet it was clear that my father needed a wife. I hoped that Debbie Stone would fill that blank, a blank that seemed to be filling like quicksand with my own name. Perhaps she could be the one to say: “Hey, everything will be fine.” “No one can cry forever — sooner or later your heart will just dry up!”

Three months after that fateful bus trip through Europe, my father married Debbie Stone. We drove down to Kansas City for the wedding. I slept in the back seat of his Chevy Malibu — “my sports car,” he said, and for years I believed Chevy Malibus to be sports cars — all the way from Minneapolis. Debbie met us on the porch in a striped terry cloth robe and an enormous smile. She looked like Jayne Mansfield with a bad perm.

“Hello, kittens,” she cooed.

I could smell her perfume, a strong, dangerous scent, and I instinctively moved back as if an animal had lunged at me. She looked and smelled nothing like my mother. When she bent down to take my suitcase, I saw that her robe was slit all the way up the side. Debbie Stone was a magnificent vixen. Surely my father was no fool to drive all the way to Kansas.

– – – – – – – – – – –

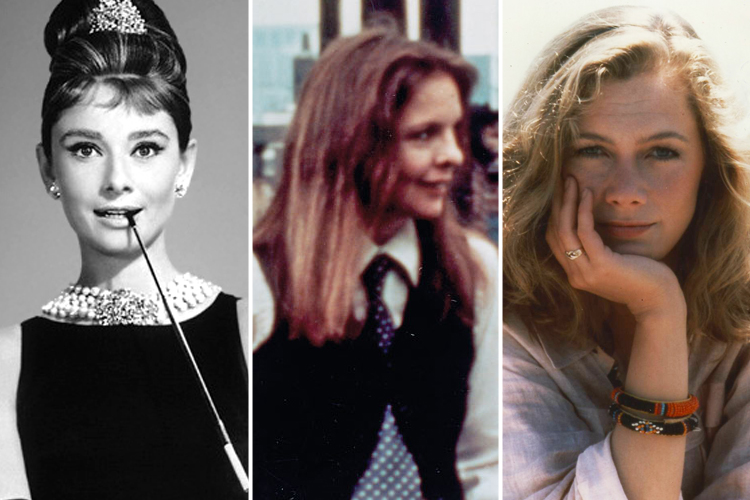

My father loved the movies with the same abandon with which he loved women. Our living room was choked with posters: Nastassja Kinski slinking in “Cat People,” kooky Barbra Streisand in “The Way We Were.” Warren Beatty shampooing Goldie Hawn above the tub. My father liked Julie Andrews in her later years, after “Mary Poppins,” and Faye Dunaway in anything. He had a certain weakness for Audrey Hepburn’s improbably enormous eyes.

My mother reminded my father of Diane Keaton in “Annie Hall.” She was quick and funny, with expressive gestures and a sharp, cascading laugh. She had a hard time making up her mind, like Annie Hall, but somehow he persuaded her to marry him when they were both very young.

But my father’s romantic appetites were unruly and impossible to satisfy. After the brief courtship and wedding to Debbie Stone, the distance between Kansas and Minneapolis was lamely bridged by weekend visits and phone calls that became increasingly strained. Perhaps he still loved my mother, or perhaps he couldn’t bear the thought of moving to Kansas and seeing my sister and me only over the summer. But at the time it seemed clear that the reason he wanted to divorce our new stepmother, only seven months after they were married, was for the simple fact that she was, in his words, “dangerous.”

Why did he believe that the very thing he’d wanted was now his demise? Maybe he’d decided, when my mother left, that all thrilling things come to disappointing ends. Maybe there were two kinds of men: the real-life Michael Douglases and Jack Nicholsons of the world, who conquered women or ruined them; and men like my father, who were ruined by women.

To get over Debbie Stone, we watched movies. The movie posters that cluttered our house came alive in the faltering blue light of the television. In “Double Indemnity,” Barbara Stanwyck plays an alluring wife with a heart of ice who lures Fred MacMurray into killing her husband. It is only after she shoots him in a rage that she turns remorseful and professes her love. Even then, when he points the gun at her and murmurs “Good-bye, baby,” she looks surprised. In “The Killers,” Ava Gardner is as treacherous as she is stunning: She cheats and deserts the man who loves her. Ultimately, his devotion is his fatal flaw.

Certainly these were characters who made bad choices and then blamed them on circumstance. But I had questions about these movies that went unanswered. When Woody Allen marries Meryl Streep in “Manhattan,” why doesn’t he know she’s lesbian? And when later he falls hard for 17-year-old Mariel Hemingway, can’t he see that love with a high school senior is doomed? Though it was clear to me that Audrey Hepburn in “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” is a party girl who answers only to herself, my father mooned over her coquettish charms. He saw the men who failed to tame her as unlucky. To me, these men did not fall in love with particular women so much as the looming rush of beautiful disaster.

– – – – – – – – – – –

A lot of time has passed. I am older than my father was when I was born. Now I know: how stupid he was, how young. He said that when I was born he used to go to grocery stores and just push the cart around the lonely aisles for hours, he felt so lost. That was not the life he imagined, he said, not at 25!

I still occasionally think of Debbie Stone: not about what she meant to us, but just of her strange yellow hair, or her brittle laugh. Since then, I have made a lot of choices. I am uncertain at this point whether the good outnumber the bad. I feared for years that I would always be, like my mother, the one to leave. And I worried that I would turn out to be like Debbie Stone: someone else’s bad luck.

And then my father fell in love again. She was young enough that she and I could have gone to high school together. She wrote poetry that she printed out in gothic font and tended to wear a lot of “sheer” blouses. They talked on the phone five or six times a day, because she moved to Chicago. She had two or three boyfriends at a time, which beautiful and crazy women, I have learned, sometimes tend to have.

I never met this girl. I worried about having a 28-year-old stepmother until my father admitted that he hadn’t yet even kissed her. But this was not for lack of effort. After all, my father learned his lesson from our favorite movies, where the heroes never give up. Think of “The Graduate.” What does Benjamin do when Elaine breaks it off to marry another guy? Who cares what Mrs. Robinson says, or that the minister has just pronounced them man and wife. He pounds on the glass wall of the chapel, screaming her name, and she runs off with him in her bridal veil, straight to the bus.

One Christmas, I got a call from Chicago. My father was at a pay phone. It was cold and windy, and the sidewalks were slicked with black ice. I could hear car stereos boom past with the bass pounding, and the sounds of two men shouting.

“Are you OK?” I said.

“Yeah,” he sighed. “Only I slipped and sprained my foot on the ice.”

Later I got the whole story. This girl never offered to pick him up or invited him to stay with her, so my father took buses and stayed in a hotel. Lost in her neighborhood, he painfully limped around looking for her address until a red-haired young woman stopped her car and asked him if he was hurt. She ended up giving him a ride. After thanking the redhead, my father chided her for picking him up.

“You’re not going to kill me, are you?” she said.

“Do I look like the dangerous type?” he asked.

“No, you’re right,” she laughed. “I guess I’ve seen too many movies.”

He finally made it to the girl’s house. She greeted him coolly at the door, smoking a cigarette. During the week he spent in Chicago, he spent five hours and 45 minutes with her; he counted.

“Wasn’t that a waste?” I scoffed.

He said no. He went to a movie at an old Chicago theater where he’d never been. The red plush seats were frayed and the popcorn had real butter, and the heroine bore a stunning resemblance to Debbie Stone, who he hadn’t thought about for years.

“What did I ever see in her?” he said. I said I didn’t know, and then considered.

“She had pretty hair,” I said, and he agreed that this was true.

For a long time after that when my father called me we would talk about the movies. Most of his old heroes got old and didn’t seem, to him, as funny anymore. Or, like Woody Allen, they have given up romantic leading roles and now seduce their heroines, their Scarletts and Penelopes, strictly from behind the camera. He didn’t believe that Jack Nicholson, in “Something’s Gotta Give,” could possibly impress Amanda Peet, much less Diane Keaton. “They would never go for that old jerk,” he said. My father goes alone to the Uptown theaters, once or twice a week, and remembers scenes and dialogue in excruciating detail. He tells me what to see, and I believe him, because movies were always the one thing for which his judgment was impeccable.