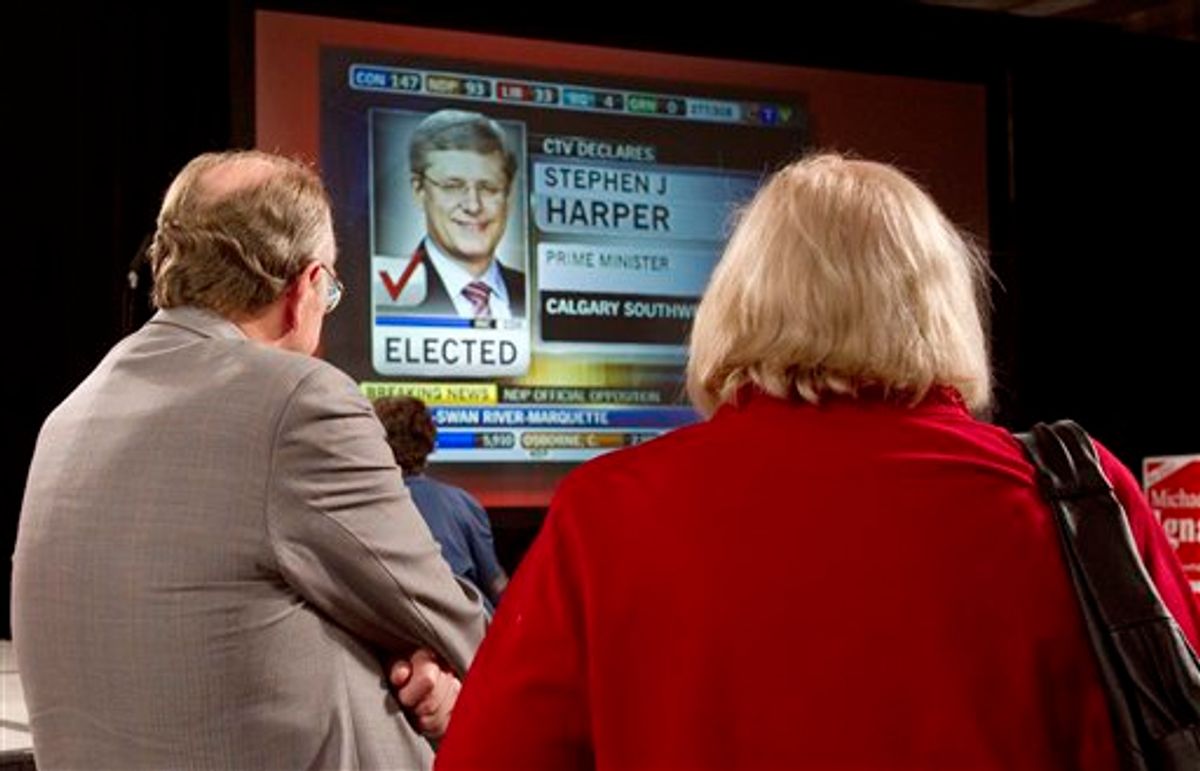

Canada's election results are historic on two fronts: Prime Minister Stephen Harper's Conservative Party won a majority of parliamentary seats for the first time in his five years governing the country, and the Liberal Party -- a powerhouse in Canada for over a century -- slipped to third place behind the left-wing New Democratic Party.

Centrist parties have historically done well, but this election seems to have created a new model that benefited a right-wing party. We spoke to political scientists at McGill University to understand what the results might mean for U.S.-Canadian relations, and for Canada's reputation as America's progressive neighbor to the north.

"This is the first Conservative majority in a very long time, and the first with a party that has originated in fiscal and social conservatism," Professor Antonia Maioni, the director of the McGill Institute for the Study of Canada, told Salon.

Maioni emphasized, however, that the Conservatives' success should not be read as a Canadian shift to the right across the board. "We now have a social democratic opposition… To see the NDP become opposition; that's a huge deal," Maioni said, noting that NDP's rise signifies a massive protest vote against a conservative majority (this was particularly forceful in Quebec, where the NDP went from one to 58 parliamentary seats).

"Maybe we've salvaged some of our progressive reputation with that," she said.

Maoni's colleague in the political sciences at McGill, Professor Eric Belanger, emphasized that "the right-wing Conservatives' strength now calls for a strong counterbalancing force on the left (or at least the center-left)."

He told Salon: "It currently appears that it is now the NDP who is seen by left-leaning Canadians (including Quebecers) as this counterweight. This campaign may have marked the end of the 'liberal consensus' in Canada and opened a new era of left-right opposition at the national level."

Maioni pointed out too that a Conservative parliamentary majority does not mean a majority of Canadians adopting a right-leaning bent: "This Conservative majority, it is only a majority of seats, not necessarily votes. This means that what Mr. Harper does going forward is not necessarily reflective of the body politic in Canada, and certainly not in Quebec."

As far as U.S.-Canadian relations go, Maioni doubted the changes in Canadian government would have any major effects.

Professor Christopher Manfredi, McGill's dean of the arts, suggested that the new makeup of the Canadian government might actually serve to strengthen relations between the U.S. and Canada, especially when it comes to negotiating border and trade issues.

"The Conservative Party is more open to the U.S. than previous Liberal policies have been," he said, adding that Harper and Obama have a strong personal relationship, since they come from the same generation and share "similar political styles."

And, of course, one of Canada's strongest claims to being America's progressive neighbor to the north has long been its healthcare system. The principle of universal healthcare in the country was at no point at issue in the election -- something Canadians can continue to boast.

Shares