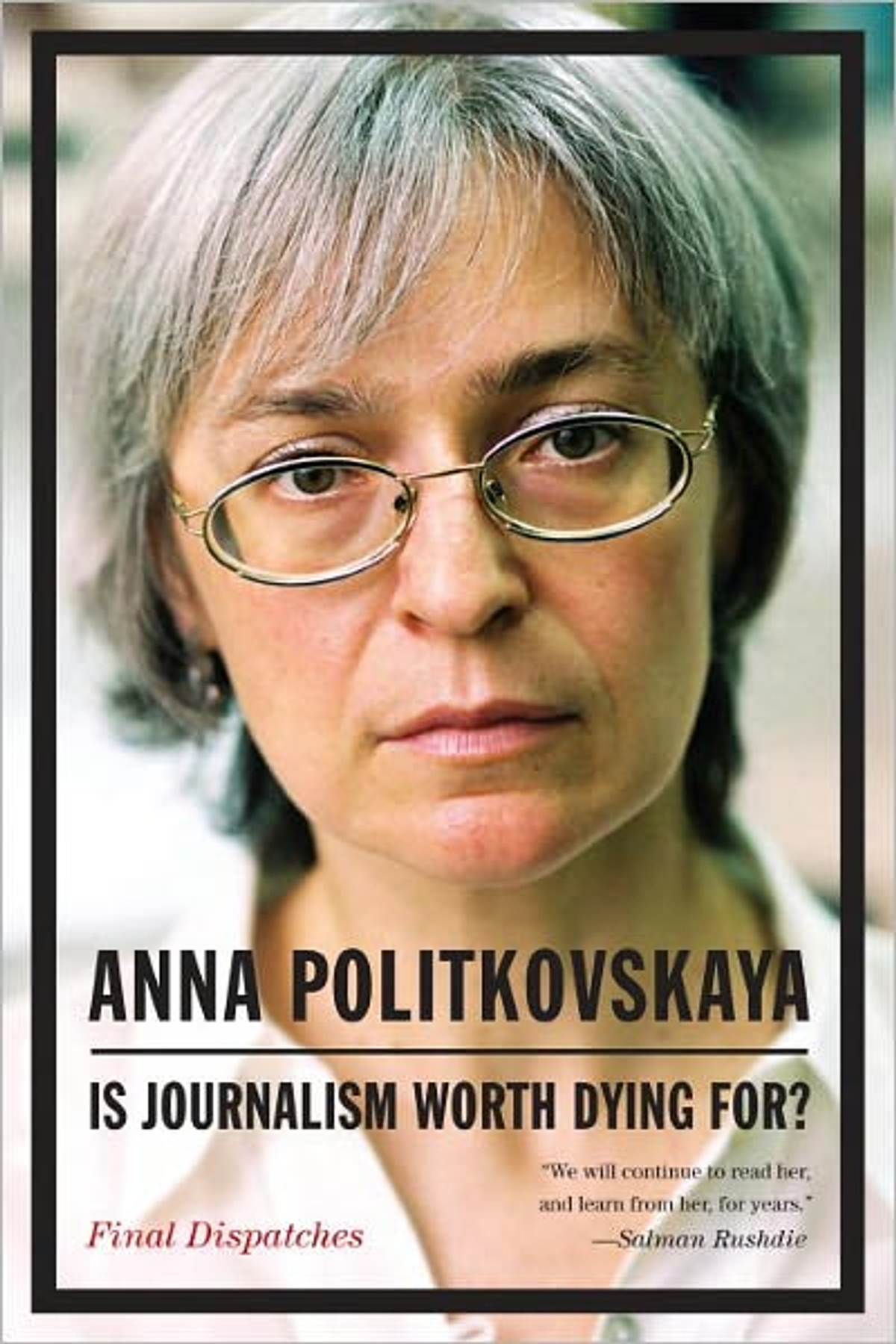

For Anna Politkovskaya, Russia was a grim country -- a "managed democracy" governed by brutal leaders and craven bureaucrats, policed by violent and extortionist security services, and reported on only by "servants of the Presidential Administration." Her crusading, obsessive journalism made her many enemies, not least inside the Kremlin; she endured beatings, poisoning, and a mock execution; but she did not back down. Murdered in 2006, her killers never found, Politkovskaya lives on in "Is Journalism Worth Dying For?," a collection of her "final dispatches."

Politkovskaya's greatest and most dangerous work was done in Chechnya, the functionally lawless region that foreign and even Russian journalists refused to enter, but to which she returned more than two dozen times. It is a terrifying place, where anarchic paramilitaries roam the streets with Berettas, politicians hit up citizens for cash, and opponents of the regime are abducted and thrown into jail cells dug into the ground, if they're not killed with impunity. And there is characteristically fearless reporting on the 2002 siege of a Moscow theater by Chechen terrorists, during which Politkovskaya attempted to negotiate with the militants to release hundreds of hostages before Russian authorities gassed the theater, killing at least 130 people. Politkovskaya argues that federal security services abetted the terrorists, a claim backed up with evidence from the former spy Alexander Litvinenko -- who was himself murdered a few months after Politkovskaya, poisoned with polonium at a London sushi joint.

Politkovskaya's greatest and most dangerous work was done in Chechnya, the functionally lawless region that foreign and even Russian journalists refused to enter, but to which she returned more than two dozen times. It is a terrifying place, where anarchic paramilitaries roam the streets with Berettas, politicians hit up citizens for cash, and opponents of the regime are abducted and thrown into jail cells dug into the ground, if they're not killed with impunity. And there is characteristically fearless reporting on the 2002 siege of a Moscow theater by Chechen terrorists, during which Politkovskaya attempted to negotiate with the militants to release hundreds of hostages before Russian authorities gassed the theater, killing at least 130 people. Politkovskaya argues that federal security services abetted the terrorists, a claim backed up with evidence from the former spy Alexander Litvinenko -- who was himself murdered a few months after Politkovskaya, poisoned with polonium at a London sushi joint.

Not all of Politkovskaya's dispatches make such forbidding reading; there are easier reports from Paris and Sydney, and even a long and surprisingly tender essay on her dog. But her enduring importance derives from her refusal to capitulate despite seemingly unbearable pressure -- and, even more basically, her commitment to rigorous on-the-ground reporting when journalists, even when not faced with official intimidation, spend more time with P.R. flacks than sources and victims. Upon her death, Lech Walesa mourned her as "a sentinel for truth," and Condoleezza Rice called her "a heroine of mine"; for the New York Times, she stood as "a symbol of what Russia has become." Only Ramzan Kadyrov, the Kremlin-installed gangster president of Chechnya and a key suspect in her murder, was unmoved. "I was not bothered in the slightest by what she wrote," he insisted, "and I have never lowered myself to trying to settle scores with women."

Shares